By: Hilal Khashan

In an April 10 teleconference meeting among Turkey, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan predicted the emergence of a new world order in the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic.

However, the events that have left the world mostly unprepared to deal with the virus do not support Erdogan’s prediction.

Some indicators suggest that a post-coronavirus world order will reflect post-World War I Europe, in which nation-states rose out of the ruins of empires.

Indeed, in the United States and Europe, nationalism appears to be growing.

But no matter how the world changes, the grouping of countries that Alfred Thayer Mahan first referred to as the Middle East in 1902 will likely continue to be defined by the power vacuum that has dominated the region since World War I.

After a history of several millennia of imperial rule, today’s Middle East state system was created by Western powers and Russia, and they continue to oversee it.

The coronavirus pandemic is in many ways revealing why this is the case.

Historical Rivalry in the Middle East

For more than three millennia, competing empires ruled the region now known as the Middle East.

The Battle of Kadesh in 1274 B.C., which took place in modern-day Syria between Pharaonic Egypt and the Hittites of the Anatolian highlands, brought stability and affluence to the Nile River Valley.

In 605 B.C., Egypt lost its influence in the Near East after being defeated in the Battle of Carchemish, again in Syria (known as Babylonia in ancient Mesopotamia). The Byzantine-Sasanian War of 602-628 weakened both Byzantium and Persia, and not long after, Muslim armies from the Arabian Peninsula seized Greater Syria from the Byzantines between 634 and 638 and defeated the Persian army in Iraq in 636. They also brought Egypt under their full control by 646 after defeating the Byzantine army there. By 651 B.C., the Sasanian Empire had fallen to Arab-Muslim troops.

Fast forward to A.D. 1514, and the Ottoman Empire had gained dominance in much of the region.

The Ottomans defeated the Safavids in the Battle of Chaldiran in west Azerbaijan and kept them out of the Middle East, which the Ottomans conquered shortly afterward.

The Ottomans also clashed with the Qajars, who inherited the Safavids, before settling their territorial divisions in the treaties of Erzurum of 1823 and 1847.

(click to enlarge)

However, the 19th century brought the terminal decline of the Ottoman Empire, which Russian Tsar Nicholas I in 1853 named the “sick man of Europe.”

In Egypt, Muhammad Ali created a modern state with French assistance, and in 1831, his son Ibrahim Pasha invaded Syria and defeated the Ottoman army in the 1832 Battle of Konya. In 1839, the Ottomans attempted to retake Syria, but Ibrahim Pasha defeated them in the Battle of Nezib.

However, at this point, the British and Austrians intervened to prevent the collapse of the Ottoman Empire — at least until they could decide how to partition it. They forced Egypt to abandon its claim to Syria in the 1840 Convention of Alexandria.

The convention also coerced Egypt to slash its army, terminate its military industry and relinquish its territorial expansionism.

The Qajar Empire did not fare better than its Ottoman rival in the 19th century, and it lost sizable territory to Tsarist Russia in the 1826-28 Russo-Persian War.

By the mid-1800s, the United Kingdom and Russia had begun to truly dominate the politics of the Middle East.

Western Intrusion and New Regional Arrangement

The time for Europe to fully dismantle the remnants of the Ottoman Empire arrived in 1915 when the Ottomans aligned with Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in World War I.

In 1916, the French and British reached the Sykes-Picot Agreement to seize Iraq and Syria.

A year later, the British government issued the Balfour Declaration, which promised to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

The United Kingdom granted Egypt, which it had occupied in 1882, its independence in 1922 and gave Iraq its independence in 1932, but it maintained military and political dominance over them.

In 1943, the United Kingdom also pressured the government of Free France to grant independence to Syria and Lebanon.

After the state of Israel was established in 1948, it reached armistice treaties with its Arab neighbors in 1949. And in 1950, U.S., British and French foreign ministers reached a Tripartite Agreement for the Middle East in which they committed to maintaining the region’s existing state order and military balance.

Notably, they understood military balance as meaning Israel’s ability to defeat the combined Arab armies. In 1955, Egypt signed a deal with Czechoslovakia to obtain modern military hardware, and from then until June 1967, Egypt worked to build itself up as a major regional power, despite a military defeat in the 1956 Suez War.

Meanwhile, in the Six-Day War of 1967, Israel demonstrated powerfully that it had no Arab military competitor. However, Israel’s title as a regional power is fairly erroneous; it is less a regional power than a Spartan state that aggressively and mercilessly defends its national interests. Its peace with Egypt and Jordan is cold and hardly goes beyond security arrangements and intelligence cooperation.

And its clandestine diplomatic ties, especially with the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council, do not qualify it to claim a leadership position or political superiority.

The Syrian Uprising Debunks the Myth of National Regional Powers

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 introduced Iran as a new Middle East regional power — especially after it involved itself in the Arab-Israeli conflict by establishing Hezbollah and sponsoring Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad.

The U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 gave strength to Tehran’s claim as regional power.

But Iranian leaders neglected to understand the implications of eliminating Iraq, which had defeated them in the 1980-88 war, as a regional competitor. (Iraqi President Saddam Hussein had miscalculated when he thought his victory against Iran entitled him to make Iraq a dominant military power in the Middle East. He developed ambitious nuclear and missile programs during the war years with Iran and expected to get away with them. The Iranians are now doing the same.)

In 2012, Iran prodded the Syrian regime to militarize the country’s uprising and transform it into a war against radical Islam, which threatened to derail Iran’s Shiite Crescent project through Iraq, Syria and Lebanon — an essential part of Iran’s strategy to secure prominent regional power status.

But by 2015, despite massive Iranian military support, the Syrian government and its many Iranian-funded Shiite allies had failed to defeat the rebels.

Russia’s active military intervention in the Syrian armed conflict beginning in September 2015 tipped the balance of power in favor of President Bashar Assad’s regime. Moscow had emerged as the decisive military and political player in the Syrian conflict, dwarfing the influence of regional players Iran and Turkey.

A few years later, Iran’s weak military response to the January 2020 U.S. killing of Qassem Soleimani, the chief of the al-Quds Brigade of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, further demonstrated the fragility of Iran’s claim to the title of regional power.

It is not an exaggeration to assert that, as a result of its direct military intervention in Syria, Russia — more than Iran, Turkey or Egypt — has become the dominant regional power in the Middle East. In February 2020, Erdogan failed to drive the Syrian army out of Idlib in northwest Syria after warning that no heads “will remain on their shoulders” if the Syrian troops did not comply with his ultimatum.

The Turkish president bit the bullet after making the statement and ended up alienating himself from the United States. Erdogan is aware that there are limitations to Turkey’s regional power ambitions in the Middle East, and he does not trust Russian President Vladimir Putin, especially since Turkey has no institutional relationship with Russia.

Erdogan chose to pursue a more pragmatic policy line in the Western Balkans. In October 2017, he visited Serbia and received a warm welcome from President Aleksander Vucic, who seemed quite willing to open up to Turkey and forget the bitter memory of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo, which resulted in an Ottoman victory and later served as the spark that ignited Serbian nationalism.

Erdogan’s venture into the European Union’s backyard has already drawn sharp criticism from French President Emmanuel Macron, who warned Turkey that the Western Balkans is off-limits.

The Coronavirus Pandemic and What’s Next

At various times in modern history, Turkey, Iran and Egypt have presented themselves as regional powers in the Middle East, but they are not strong enough nations to avoid the political and military influence of more powerful countries.

Even though the Egyptian economy is improving, the majority of Egyptians are getting poorer because economic expansion occurs mostly in the oil and gas sectors, which employ only a small percentage of Egypt’s labor force.

The coronavirus threatens to destroy Turkey’s emerging economy, which has only recently started to recover from the financial crisis of 2018. Meanwhile, the Iranian economy is shattered. The virus is wreaking havoc on the Middle East’s already flagging economies, and wild protests are likely to spread to the area’s core countries after the pandemic abates.

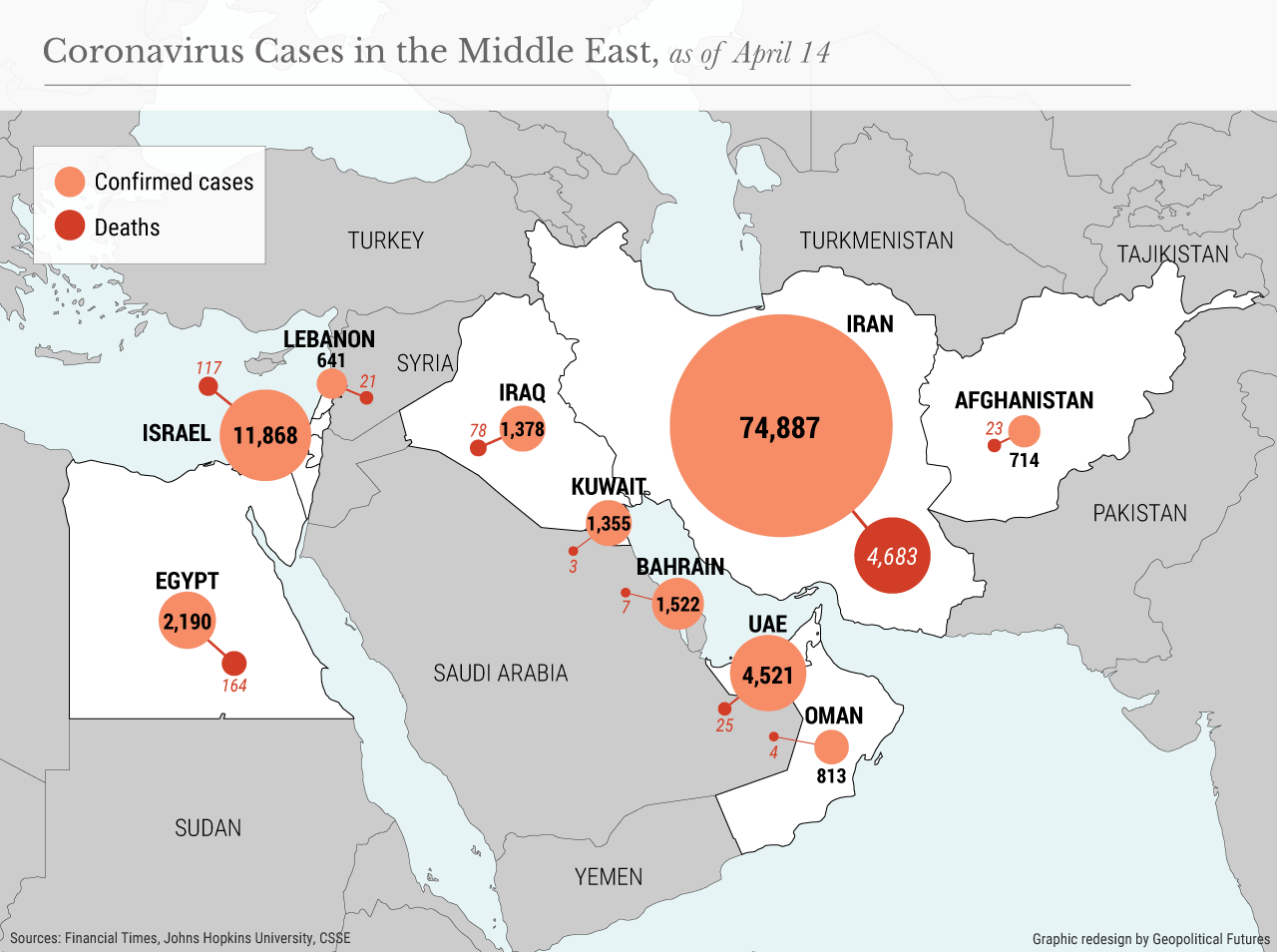

(click to enlarge)

The upheaval resulting from the virus has brutally exposed the structural weaknesses of the Middle East’s inherently rigid political systems, which have failed to address their unprecedented national emergencies, instead approaching the virus with denial, blame and misinformation.

Lack of transparency and suppression of medical reports about the extent of the spread characterized the initial response of the Turkish government. A reluctant Turkey waited until March 11 to report its first confirmed case of COVID-19 and even then declined to inform the public about its location.

Neither Turkey nor Iran has yet managed to flatten the curve of the virus’s exponential growth. (The fact that Turkey is having difficulty containing the virus did not seem to prevent Erdogan from airlifting medical aid to Italy, Spain and the Western Balkan countries.)

The Egyptian government, meanwhile, has taken an official stance of belittling the virus’s impact.

This approach has contributed to a nonchalant public attitude and has resulted in a country with no clue about the real extent of the virus’s (seemingly rapid) spread within it.

In Iran, President Hassan Rouhani has warned his people that they have to live with the virus for an extended period, and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei did not hesitate to accuse the United States of launching biological warfare in his country.

Rouhani is reluctant to declare a national lockdown partially because, in addition to the devastating economic implications, it would commit the armed forces to the streets and give additional leverage to the conservative clerics who control them.

Authoritarianism, which is rampant in the Middle East, increases in times of societal crises such as natural disasters, economic collapse and wars. These crises further aggravate existing imbalances in civil-military relations and increase executive power at the expense of the legislature and civil society.

The coronavirus pandemic has redefined the meaning of power and introduced the quality of the public health sector as a key independent variable in assessing the strength of a country. (Military might, after all, has proved useless in fighting the virus.)

Rule by fear and excessive coercion are exacerbating authoritarian tendencies in the Middle East, and further alienating the people from the state. Public apathy and antipathy toward the ruling elite do not bode well for the future of the region.

The leading countries of the Middle East may hope that in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, a new world order will allow one of them to become a true regional power.

But right now, their weaknesses, combined with the historical strengths of Western and Russian powers, suggest that much will remain the same.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario