The Indo-Pacific After COVID-19

By: Phillip Orchard

In late March, senior officials from the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, a loose coalition of the Indo-Pacific’s four most powerful democracies, quietly launched a series of meetings aimed at forging a coordinated response to the coronavirus pandemic.

"The Quad" (comprising Japan, Australia, India and the United States) has come to symbolize both the grand plans of those seeking to cement the Indo-Pacific’s status quo and the more complicated reality of a region in flux.

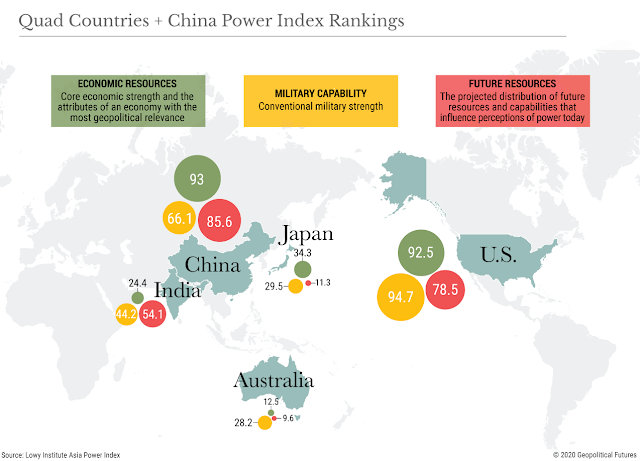

On paper, the Quad makes sense as a potent alliance capable of pooling immense resources and leveraging distinct geographic advantages to limit Chinese influence and deter Chinese attempts to establish military dominance in the Indo-Pacific — especially if other regional states such as Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea could be enticed to join.

In reality, though, the Quad has been slow to coalesce into something equaling more than the sum of its parts, due in large part to economic fears of antagonizing China and inadequate budgets that cannot keep up with China’s breakneck military modernization. Though military cooperation has increased modestly among its members, the grouping itself has struggled to implement any substantive joint initiatives, much less forge an integrated security alliance capable of pulling off complex military coordination in a combat environment.

The COVID-19 pandemic could realistically push the Quad — and thus, the future power balance of the Indo-Pacific — in a number of directions. There’s a scenario in which members rise to the occasion, realize their capacity for collective action and reinforce the regional multilateral architecture ahead of the daunting challenges to come.

On the other end of the spectrum is an outcome where the virus guts members’ military budgets, saps political support from multilateral initiatives and presages an era of regional disorder that China can reshape to its tastes. The United States, more than any other country, will determine which direction the Quad goes.

Quad Goals

For those alarmed by China’s military buildup, the idea of the Quad is certainly seductive. The three non-U.S. members are ideally positioned to exploit China’s biggest geographic dilemma: its dependence on sea lanes that run through chokepoints in the first island chain and the Strait of Malacca.

To deter Chinese aggression, the thinking goes, Quad members could threaten to cut off Chinese maritime traffic at these chokepoints. India, which has grown increasingly concerned about encirclement by China's People's Liberation Army, would ostensibly be tasked with blocking the mouth of the Malacca Strait from its bases in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Japan, whose near-total dependence on imported natural resources makes it particularly vulnerable to sea lane threats, would cover the East China Sea down to New Guinea. Australia, itself highly dependent on global sea lanes and wary of China’s push into the Coral Sea, would cover the southern outlets through Indonesia.

In coordination with U.S. firepower, these positions would form a tight containment line. But the approach would also provide a degree of reassurance to Japan, Australia and India that their ability to deter China doesn’t hinge solely on a distant, distracted United States’ appetite for conflict.

This, in turn, would allow the group to woo other strategically located regional states — ones like the Philippines and Indonesia, whose own concerns about U.S. commitments have made them exceedingly reluctant to anger China.

Unlike the United States, Japan, Australia and India can’t one day decide to simply leave the Indo-Pacific. Indeed, in Southeast Asian states where tight cooperation with either China or the U.S. is politically problematic, partnerships with the other Quad states have proved to be welcome alternatives.

Quad Problems: Money Matters

Of course, geopolitical competition isn’t as simple as a game of Risk — and the COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to alter nearly every component of the regional landscape. For one thing, the military balance is only part of the equation. To prevent strategically valuable countries from concluding that siding with China (or, at minimum, refusing to cooperate with Quad members) is in their best interest, the group also needs a comprehensive — and invariably expensive — soft power strategy involving hefty economic and security assistance.

Moreover, China has ample ability to hurt each of the Quad members outside the military realm. More than a third of Australian exports head to China, for example. (Australian wariness of angering China after the 2008 financial crisis was central to the demise of the first version of the Quad.) India, among other things, is worried about China’s ability to use Pakistan as a proxy to keep the Indian military bogged down in Kashmir.

Japan is the most willing to challenge China, but even it is dependent enough on Chinese consumers and supply chain links that it is typically keen to keep relations with Beijing reasonably stable.

If China weathers the pandemic fallout better than most, its economic leverage over regional states would almost certainly increase. (Many regional states are in a fix either way; if China's economy can’t pull out of its COVID-19 tailspin, Japan’s and Australia’s economies will go down with it.)

Quad Problems: Military Might

Still, the military balance factors into nearly all other aspects of regional relationships; countries are much more likely to cede to Chinese demands on oil drilling in the South China Sea, for example, if they believe that it is impossible to stop China from settling the dispute by force. To be sure, Japan, India and Australia don’t need to be able to match China, which is on track to build a 425-ship navy by 2030, ship for ship.

They just need to be confident that each would be willing and capable of controlling certain maritime chokepoints in tandem, thus providing enough of a threat to Chinese shipping to convince Beijing that it is better off living with the status quo.

But while the pandemic’s economic toll creates incentives for deeper cooperation among the non-U.S. Quad members — it’s certainly cheaper to share base networks and divide up responsibilities — the crisis will make it even harder for the Quad to reach the sustained military spending needed to project sufficient power in distant waters.

This would be especially crucial in a scenario in which China remains ascendant and the United States loses interest in putting its blood and treasure on the line in the Indo-Pacific. It’s just very hard and very expensive to build a force capable of matching China in multi-domain operations.

The non-U.S. Quad member most capable of doing this over the long term is Japan. But as it stands, the Japan Self-Defense Forces are a superb complementary force tailored to operate close to home in tight coordination with the United States. To replicate the roles that the United States presently fills, Japan would need to dramatically reorient its force structure and procurement priorities, shed steep legal constraints and surge spending indefinitely (and go nuclear, for that matter). It won’t happen fast.

In a conflict in the East China Sea in the next decade, Japan would be unable to rely on India and Australia; even if the countries were fully committed to Japan’s defense, their forces would be too far away to help. Their ability to disrupt Chinese maritime shipping in their respective areas could act as a deterrent against Chinese aggression elsewhere.

But if Beijing was willing to accept the cost and concentrate its forces to secure access to the Pacific, Japan may be overmatched. The odds would be stacked even higher against Indian (set to spend some $73 billion on defense this year, the bulk of it on personnel costs) or Australian ($27.5 billion) forces if China tried to make a break for it in their respective domains.

These scenarios expose another problem inherent in the sort of decentralized alliance that would result without robust U.S. leadership. It’s too easy for strategic interests among coalition partners to diverge and for an adversarial power to exploit the cracks — especially a country with China’s coercive capacity in the economic, cyber and diplomatic realms.

Symbolic shows of unity that aren’t backed up by real readiness to act collectively are not a deterrent. At the end of the day, if India, for example, thinks Japan, Australia and the United States would not help enough for it to win an Indian-Chinese conflict at an acceptable cost, then it has ample reasons to limit tensions with China — even if that means capping military cooperation with its Quad partners at a level that won’t incur major retaliation from Beijing.

The U.S.-China Dynamic at the Center

All these problems make clear that the Quad’s future will be primarily determined by the fates of its most powerful member, the United States, and the group’s raison d'etre, China. While Beijing appears to have handled the pandemic relatively well so far, it’s still facing truly immense economic and political pressures as the world sinks into a deep recession.

If the fiscal constraints exposed by the crisis lead to a dramatic reversal in spending on China’s military and its Belt and Road Initiative — or, of course, if they cause China to collapse into an inward-focused basket case of political mayhem — then Quad members could lick their own wounds in peace, and the regional status quo would survive.

But let’s say the Communist Party of China muddles through the immediate economic crisis intact, leans on military spending as a form of stimulus, invokes external aggression to curry nationalist support and tries to use the pandemic to reveal that its neighbors’ best bets for prosperity lie in a Sino-centric order. The question then centers on how the U.S. bounces back from the pandemic.

The United States, for example, won’t be immune to deep cuts in military spending — even if such cuts were more the result of political forces than fiscal constraints. It took the better part of a decade for Pentagon budgets to recover from sequestration following the 2008 crisis. This time around, as the death toll from coronavirus climbs toward levels seen only in U.S. wars and the U.S. economy sinks into a deep recession, the pressure to redirect spending will be immense.

The more overstretched the U.S. military becomes, the less it will invest in expensive assets that will be vital in 20 to 30 years — and the more regional friends and allies will worry if they can really depend on U.S. defense commitments. A U.S. aircraft carrier getting sidelined in Guam at a time when Chinese vessels are ramming Japanese warships, sinking Vietnamese fishing boats, locking weapons on Taiwanese jets and flooding the Spratlys doesn’t exactly inspire confidence, even if the U.S. Navy wasn’t going to stop Chinese “salami-slicing” anyway.

Perhaps a bigger issue for the United States is regional concerns about the U.S. ability to continue delivering public benefits — and these are growing amid the pandemic. Since World War II, the U.S. role as guarantor of open sea lanes, its advocacy for a rules-based trading system, and its unmatched ability to take on global leadership roles in the face of natural disasters and shared threats have all been immense sources of American power.

The brilliance of the U.S. approach was its focus on building systems — on setting out relatively clear rules, expectations and benefits, and inviting just about anyone to participate. These systems created a sense of certainty and stability around which countries could organize themselves, expanding U.S. influence and, at least over the long term, supporting U.S. interests without requiring U.S. omnipresence.

For various reasons — chief among them China’s challenge to the rules-based order and internal U.S. political pressures — Washington has moved toward ad hoc, transactional means of pursuing short-term interests. This, incidentally, is how China prefers to play the game of influence.

It prefers bilateral settings in which it can tailor its coercive tools around a counterpart's specific vulnerabilities and chip away at the regional order bit by bit. The problem for the United States, at least in the Indo-Pacific, is that China, with its focus comparatively confined to a single region, is better positioned to channel its resources and sustain this approach. If it's every country for itself in the Indo-Pacific, China thrives.

The problem for China, however, is that, even if it wanted to, it can never replicate the U.S. role as a benevolent hegemon at the center of a mutually prosperous order. It’s physically too close to the other countries in the region, and its strategic and material needs are too immense.

Moreover, China’s role in unleashing the coronavirus on the world will only deepen regional wariness of the Chinese Community Party, no matter how many masks and tests it distributes in an effort to portray itself as a regional benefactor.

The country is stuck taking an inherently coercive approach, and coercion isn’t a great way to win lasting trust and support if there's an alternative. These conditions create space for groups like the Quad to take root. It’s just a matter of whether the U.S. reemerges from the pandemic ready to lead.

Home

»

Australia

»

COVID-19

»

Geopolitics

»

India

»

Japan

»

The Quad

»

U.S. Economic And Political

» THE INDO-PACIFIC AFTER COVID-19 / GEOPOLITICAL FUTURES

viernes, 24 de abril de 2020

Suscribirse a:

Enviar comentarios (Atom)

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario