Emerging Markets Need a Better Safety Net. It Already Exists.

Central bank swap lines have prevented a global liquidity crisis. They could also pave the way to finally provide currency stability to developing countries

By Jon Sindreu

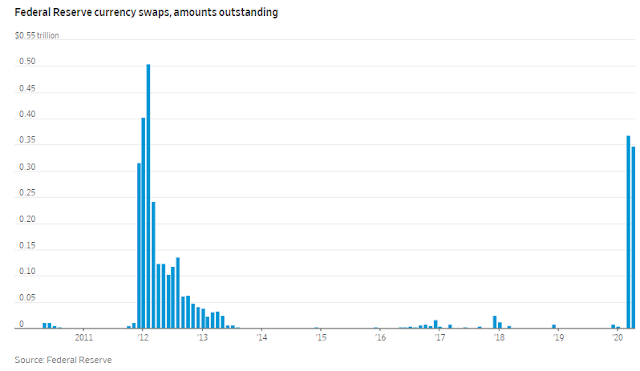

In the Covid-19 crisis, central banks’ currency swap lines may offer a way to radically reshape the global monetary system while changing very little.

Emerging economies cannot afford the huge fiscal packages announced by Western countries to counter the impact of the pandemic. More than 90 countries have now asked the International Monetary Fund for help. The IMF may even lend money without its usual imposition of budget cuts.

But even so, it will need to be paid back, and is unlikely to be enough to offset fickle global capital flows: Outflows from emerging-market assets amounted to a record $83 billion in March, according to the Institute of International Finance.

Oil exporters, like South Africa in particular, risk following Argentina and Lebanon in defaulting on debt payments. The MSCI EM Currency index, down 6% this year, has much further to fall if it follows the pattern of 2008.

The key danger is a prolonged economic slump, and the IMF isn’t designed to give nations the freedom to spend their way out of it. A new system needs to be set up that circumvents the key financial constraint on emerging markets: Central banks can buy domestic government debt, but can’t print other nations’ money.

Both rich and poor countries outside of the U.S. are now grappling with the pre-eminence of the dollar as the ultimate international settlement currency. Foreign greenback debt amounts to $12 trillion, figures by the Bank for International Settlements show, and in periods of crisis companies struggle to find enough dollar liquidity.

The Federal Reserve is managing this by providing dollars to other major central banks through swap lines. Emerging markets should have access too. As of last week, the Fed now allows them to exchange their Treasury holdings for dollars. The IMF could also launch short-term emergency lines that allow for quicker liquidity support.

But ample liquidity at the market exchange rate won’t be enough for poor nations. They also need that rate to be made stable.

In a developed country like the U.K., the post-Brexit slide in the pound didn’t trigger an economic downturn, because the loss of purchasing power for Britons was small and there are always investors willing to buy U.K. assets after a fall in sterling.

If Argentina’s exchange rate falls too much, however, this in itself creates a self-fulfilling prophecy that wrecks the economy. Importers may no longer be able to afford vital goods. The only options left are capital controls or borrowing from the IMF, which often makes matters worse.

There is an alternative: The world’s central banks could agree to repurpose swap lines to finance distressed balances of payments. They could set floors—and ceilings—on each pair of exchange rates, making central banks the “value investors of last resort” for currencies.

This would limit panics, but also cap how low developing nations can set their currencies to rob exports from others—a charge often leveled against China. The IMF could regularly set wide bands around what it calculates each country’s currency to be actually worth in real, purchasing-power terms. Unlike in the days of the gold standard, this is what now ultimately anchors currency values.

A stabler world economy would benefit everyone, and investors would still be able to trade currencies within these bands. Of course, it would require central banks to swap as much money as necessary at those preset rates. But the history of monetary policy shows that lending freely at punitive rates provides a much better cushion than generous but limited bailouts.

The IMF was created in 1944 to provide aid in exchange for discipline, but a modern globalized economy requires a more elastic approach. The good news is that, for the most part, it is already in place.

Home

»

Central Banking

»

Economics

»

Emerging Markets

» EMERGING MARKETS NEED A BETTER SAFETY NET. IT ALREADY EXISTS / THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

viernes, 10 de abril de 2020

Suscribirse a:

Enviar comentarios (Atom)

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario