Bad Blood

by: The Heisenberg

Summary

- "Generational event" is about the closest one can come to capturing the gravity of what's going on both in markets and in society more generally.

- There is no modern precedent for the situation in which we find ourselves, and in keeping with that, the policy response has been unprecedented.

- We've quite obviously passed the point where comparisons to Lehman are adequate to convey the scope of the crisis.

- "Where to from here?" is a question no one can currently answer.

- There is no modern precedent for the situation in which we find ourselves, and in keeping with that, the policy response has been unprecedented.

- We've quite obviously passed the point where comparisons to Lehman are adequate to convey the scope of the crisis.

- "Where to from here?" is a question no one can currently answer.

"How bad do you think it's gonna be?," Al Pacino's Michael Corleone asks Clemenza, in one of the many iconic exchanges from The Godfather.

"Pretty bad," Clemenza remarks, matter-of-factly, before shrugging off the coming war as a kind of Schumpeterian necessity.

"That's all right," he says. "These things gotta happen every five years or so. Ten years. Helps to get rid of the bad blood. Been ten years since the last one."

I) No atheists in foxholes

It's been more than ten years since the last crisis, so Clemenza would probably say we're due.

Even as the vast majority of market participants have adopted some form of the old "There are no atheists in foxholes" adage when it comes to dropping their usually strident defense of Libertarianism (even Cliff Asness admits we need government in the fight against the pandemic), there are some intelligent arguments for allowing the current crisis to "help get rid of the bad blood."

Goldman, for example, recently argued that the oil shock will be a game-changer for an energy industry which has long needed a reset. In a note dated March 30 that found the bank discussing "the largest economic shock of our lifetimes," the bank's Jeff Currie wrote the following:

We believe the current oil crisis will see the energy industry finally achieve the restructuring it so badly needs. We have long argued that it is the supply and demand of capital that matters, not the supply and demand of barrels; as long as there is capital, companies can withstand difficult periods and the barrels always come back. The difference between today and 2015/16 is that shale and high-cost oil producers were already facing sharply higher costs of capital over the past year due to persistently poor shareholder returns. Indeed, these capital restrictions have only been exacerbated by recent events, whereas in 2015/16 capital never dried up – making the likelihood of capitulation by US E&Ps and EM producers much higher today.

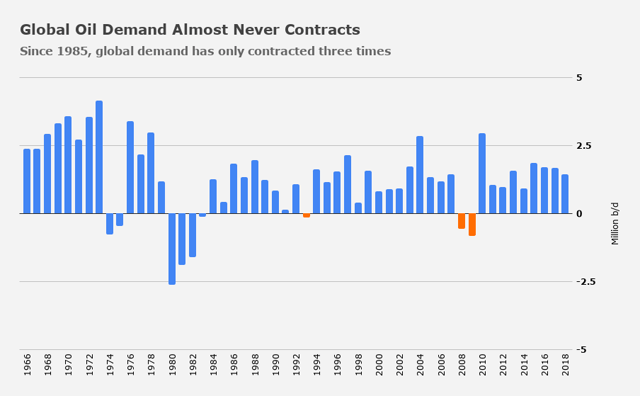

Goldman pegged the near-term daily demand destruction at 26 million b/d. Oil demand, you'll note, almost never declines on an annual basis. But it will in 2020. The only question is by how much.

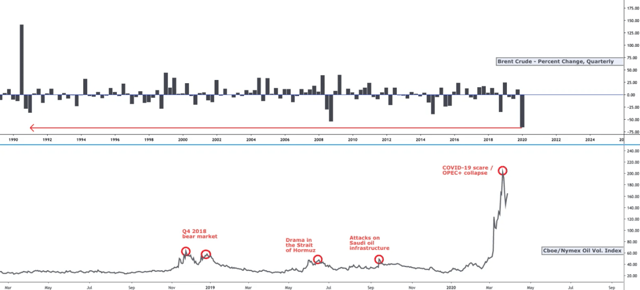

Russia and Saudi Arabia (at Donald Trump's urging) are tentatively working towards some manner of production cut deal, and the promise of an emergency OPEC+ virtual meeting next week helped push crude to its best weekly gain on record. But, on Friday and Saturday, Riyadh and Moscow traded barbs, underscoring the intractability of the stalemate.

Even an agreement on a 10 million b/d cut (a figure floated by Trump, Vladimir Putin and unnamed OPEC delegates) would fall well short of offsetting the unprecedented demand destruction brought about by the travel restrictions and other containment measures adopted globally in the fight against the coronavirus.

This is obviously devastating for many US producers, who won't take any comfort in the notion that their sacrifice is part of a broader economic reset that will help purge years of misallocated capital.

The oil story isn't merely a sideshow to the pandemic. The price war (narrowly construed) is tangential, but the potential for the collapse in prices (which fell the most in history during the first quarter) to make an already bad economic situation worse, is real indeed.

"While many consumers, companies and countries benefit from lower oil prices, there are serious repercussions for others," Howard Marks wrote, in his latest memo, before laying out the knock-on effects as follows:

- Big losses for oil-producing companies and countries

- Job losses: the oil and gas industry directly provides more than 5% of American jobs (and more indirectly), and it contributed greatly to the decline of unemployment since the GFC

- A significant decline in the industry’s capital investment, which recently has accounted for a meaningful share of the U.S.’s total

- Production cuts, since consumption is down and crude/product storage capacity is running out

- The damage to oil reservoirs that results when production is reduced or halted

- A reduction in American oil independence

If you're ever looking for a corner of the market where almost no one with a vested interest is willing to make any arguments about the relative merits of purging "misallocated capital," it's in the U.S. oil patch.

At a higher level (i.e., for corporate America as a whole), the "scourge" of misallocated capital is to a large extent the product of post-crisis monetary policy. This is a point folks like myself have been making for years, and it's neatly encapsulated by Marks in the same memo linked above. To wit:

Many companies went into this episode highly leveraged. Managements took advantage of the low interest rates and generous capital market to issue debt, and some did stock buybacks, reducing their share count and increasing their earnings per share (and perhaps their executive compensation). The result of either or both is to increase the ratio of debt to equity. The more debt a company has relative to its equity, the higher the return on equity will be in good times, but also the lower the return on equity (or the larger the losses) in bad times, and the less likely it is to survive tough times. Corporate leverage complicates the issue of lost revenues and profits. Thus we expect to see rising defaults in the months ahead.

This speaks to the irony of the Fed's multi-pronged corporate bond buying program announced late last month alongside a raft of additional measures. We are in no position to allow misallocated capital to be "purged."

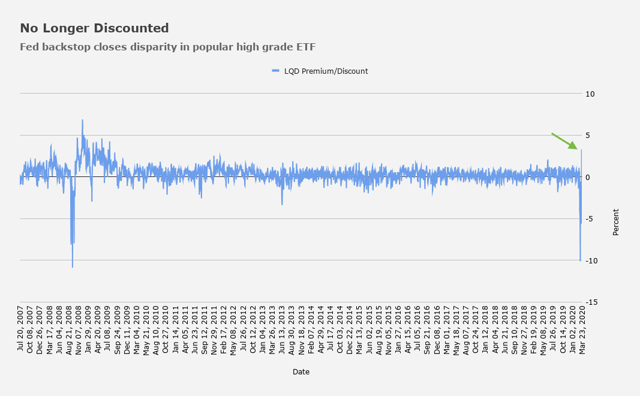

A microcosm of this is what happened last month to the iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF (LQD), which, in the course of free-falling, traded extremely wide to NAV. It was, colloquially speaking, "broken," something fixed income ETF critics have long warned would happen eventually. When the Fed announced its foray into corporate bond purchases, it said the following about ETFs:

The SMCCF will purchase in the secondary market corporate bonds issued by investment grade U.S. companies and U.S.-listed exchange-traded funds whose investment objective is to provide broad exposure to the market for U.S. investment grade corporate bonds.

That was on March 23. Almost immediately thereafter, LQD surged to the largest premium over NAV in a decade (see the visual).

It traded at a slight discount as of Friday, but you get the point.

Just to drive it home, short interest on LQD now sits at just 1.48%, according to data from IHS Markit. It was 17.6% on March 12. "The short base collapsed in speculator fashion… after the Fed’s credit backstop programs," JPMorgan's Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou remarked, in a Friday note.

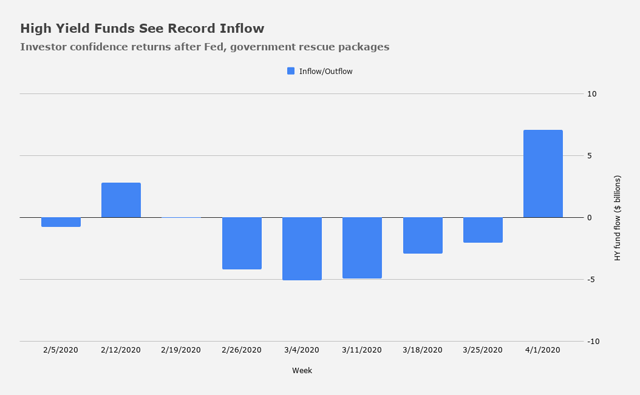

Meanwhile, high yield funds saw their largest inflow on record in the week through Wednesday, according to Lipper data.

Although junk isn't eligible for Fed buying, renewed confidence in high yield (which, as a whole, now trades back below the "distressed" threshold of 1,000 basis points) is clearly down to the central bank backstop for credit markets and the government's $2 trillion stimulus package.

Amid the cacophony on places like Twitter and various blogs, it's important to note that most of the actions taken by the Fed are necessary. I talked at length about this in my last post for this platform, and I've documented the specifics of each and every Fed emergency facility elsewhere, but I want to quickly touch on the foreign repo facility rolled out this week.

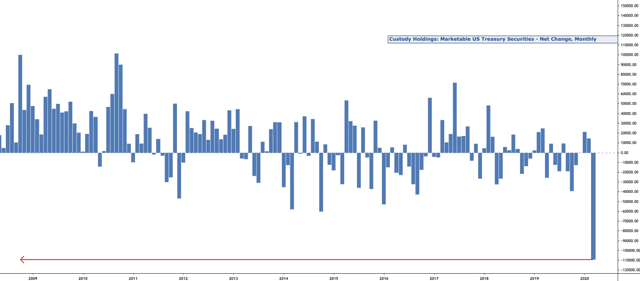

Long story short, the facility allows foreign central banks to post their Treasurys for dollars, which can then be made available to entities in other locales. As the Fed explained, "the facility reduces the need for central banks to sell their Treasury securities outright and into illiquid markets, which will help to avoid disruptions to the Treasury market and upward pressure on yields."

The Treasury market effectively broke last month and became extremely illiquid in the process.

With data for the full month now available, we know that foreign central banks sold nearly $110 billion of Treasurys in March. That's the most on record - and it's not even close.

That speaks to the March market mantra which, summed up, was "sell everything that isn't tied down to raise USDs."

Although the Fed’s swap lines were extended last month to include Australia, Brazil, Denmark, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore and Sweden (in addition to the standing arrangements with the BOC, the BOE, the BOJ, the ECB and the SNB), that’s just 14 central banks.

You have to remember that in situations like these, there are dollar pegs that need to be maintained, and during times of acute stress accompanied by USD strength, interventions aimed at stabilizing local currencies are sometimes necessary.

Throw in the USD funding needs of corporates in foreign locales, and it's apparent the swap lines either weren’t adequate, weren’t enlarged enough (i.e., the Fed didn’t cast a wide enough net) or some combination of both.

That's why the foreign repo facility is necessary.

Similarly, the decision to exempt Treasurys and deposits at Federal Reserve banks from the supplementary leverage ratio is probably necessary too, all criticism aside.

Yes, it will increase leverage at banks, but without the interim rule (announced on Wednesday to jeers from the social media peanut gallery, where everyone suddenly became a regulatory crusader), the behavior of market participants in light of recent turmoil and the effects of the policy actions taken to ameliorate that same turmoil could have ended up curtailing banks’ capacity to intermediate and lend.

In short, all of this has to be propped up, bailed out and otherwise inoculated.

If it's not, the domino effect would be catastrophic, and although the cavalier among you may be inclined to bravely parrot the "let it all burn" line, I doubt you really want that.

As you might have noticed, the $2 trillion virus stimulus bill was passed without much hand-wringing about "paying for it." That's another "no atheists in foxholes" moment, but, perhaps just as importantly, it exposes the truth behind the deficit myth.

The daily budget wrangling inside the Beltway doesn't reflect reality. There is rampant confusion in this country about how money actually works, and that confusion is at the heart of the vociferous opposition to Modern Monetary Theory. Consider the following crucial passages from Stephanie Kelton (these are from a shorter version of a more detailed piece that eventually appeared in The Intercept):

What does it mean to say that Congress is “paying for” its spending? I worked in the Senate, and the phrase has a concrete meaning in the budget world. When a member of Congress drafts a bill, staffers often shop it around, looking for support from other members.

Inevitably, the first question that staffer gets is, “What’s your pay-for?” So, for example, if you have a $1 trillion infrastructure bill, they want to know how you plan to fully offset that spending so it won’t add to the deficit. That’s what it means to “pay for” spending.

This usually involves raising taxes. If you can bring in enough new “revenue,” you can claim that you “found the money” to fully “pay for” your spending. This is the idea behind PAYGO –Pay As You Go – don’t add to the déficit.

When Congress passes a spending bill that is fully “paid for,” it sends two sets of instructions to the Federal Reserve. The first set of instructions tells the Fed to mark up the size of certain bank accounts (as the spending takes place).

The second set of instructions tells the Fed to mark down certain other accounts (as people/companies pay more taxes). On balance, PAYGO is meant to result in the government subtracting away (via tax) exactly as many dollars as it adds (via spending).

We have been misled (suckered) into thinking that this is the epitome of “fiscal responsibility.” That “paying for” your priorities shows that a politician is “serious” and that his/her plans are “credible” because the “math adds up.” That is malarky!

Congress always has the power to pass legislation that sends only one set of instructions to the Fed. That’s what it is doing now. No one is trying to “pay for” a $2 trillion spending package to help cushion the economic blow to our economy.

It would be insane to try to offset that spending right now. Why? Because our economy runs on spending. And right now, spending is collapsing. We want the Fed to add to bank accounts without subtracting away more.

There's a lesson here. Although there are, of course, limits to how much spending can be authorized without offsets, those limits are dictated by inflation. Quite obviously, inflation isn't something we need concern ourselves with in an environment characterized by the single largest demand shock of the past century.

"On the Austrian analysis, recessions give a chance to re-allocate ‘mal-invested’ productive factors to efficient uses [and] they should therefore be allowed to run unhindered until they have done their work," Robert Skidelsky wrote, in Money and Government.

He then reminded readers that "economists whose common sense had not been completely destroyed by their theories rejected the drastic cure of destroying the existing economy in order to rebuild it in the correct proportions."

Now, about our "existing economy" - it's disintegrating rapidly. Read on.

II) Nicci

"What do you think about all of this?," read a text message that materialized on my iPhone screen around 6:15 AM on March 23.

It was alarming. Nobody sends me text messages, let alone early in the morning. Besides that, it was annoying. As regular readers are aware, 6:00 AM is my cigar/espresso hour - interruptions are not generally welcome.

Through the pre-dawn mist on the back deck, the mechanical glow from the phone alert was hard on my unadjusted eyes.

I met Nicci on the very island I now call home when we were teenagers. She was born here, and will always consider me a "tourist," despite her having left, and me now being a property owner. She introduced me to bioluminescent tides before either of us were old enough to drink, but in that era, "age was just a number" when it came to alcohol consumption, so my first experience with a glowing ocean was amplified by cheap vodka.

As a teenager (and into her early twenties), Nicci was an idealist with a biting sense of humor - Ocasio-Cortez without the political ambition, if you like. As these things go, the flame of youth eventually flickered, giving way to a kind of dim, barely-burning candle. Somewhere along the way, she got into the restaurant industry and eventually became a sommelier.

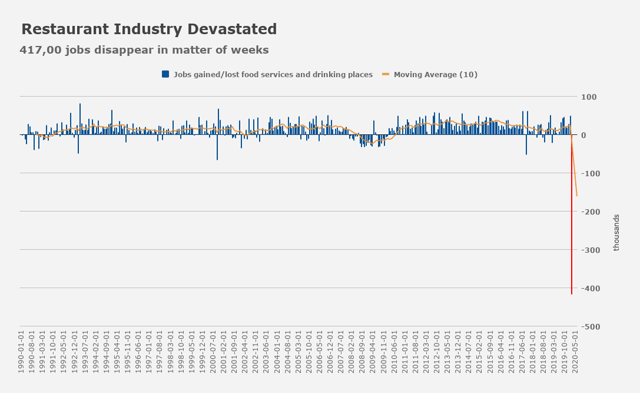

The current economic situation has laid waste to the services sector, and Friday's jobs report (which, as you're doubtlessly aware, came in much worse than expected) showed that two-thirds of the 701,000 monthly decline was accounted for by the leisure and hospitality industry.

The 459,000 positions lost meant that nearly two years' of gains were wiped out in a single month.

Out of that 459,000 decline, 417,000 was accounted for by the “food services and drinking places” category.

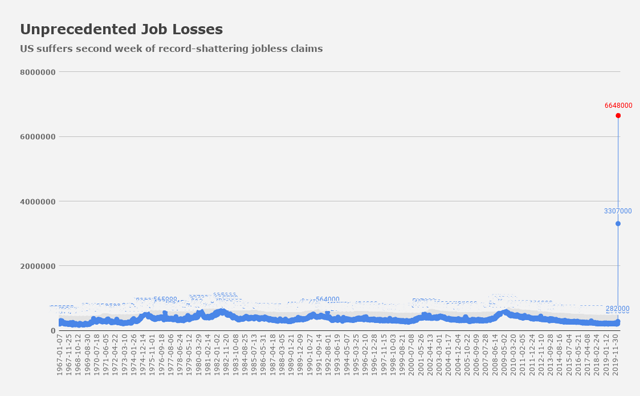

Here is an astonishing chart:

Despite coming in nearly 7 times worse than the median estimate, Friday's jobs report understates the severity of March's surge in joblessness. As most readers are probably aware, the survey period did not capture the darkest days of the month for the American economy, as many of the stricter stay-at-home orders and mandatory business closures came during the latter half of March.

For that reason, weekly claims figures have become far more germane for market watchers. Indeed, in the days ahead of the March 26 release, economists across the country (simply utilizing state-level data and anecdotal accounts) warned that America was about to witness a spike that would dwarf anything seen in the history of modern economic statistics.

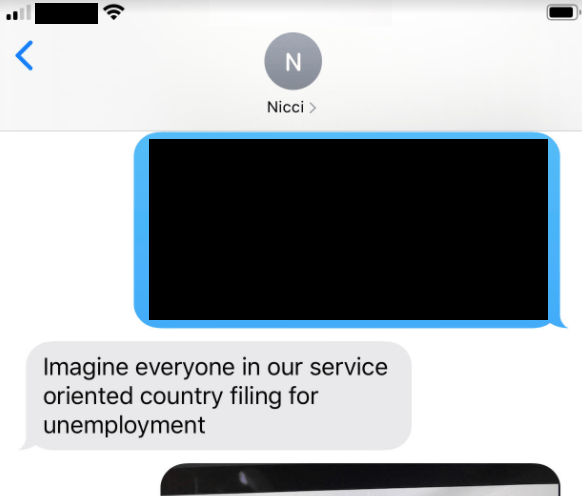

Nicci is no economist. She's a wine steward. But in our morning text exchange on March 23, she was unequivocal about what was coming. And not because she had been reading the finance page - rather, because she works in (or I guess with, is more accurate) the industry. Have a look:

And they did - file for unemployment, that is.

Three days later, jobless claims for the week of March 21 printed quadruple the previous record from 1982. On Thursday of this week, they skyrocketed to 6.65 million.

.

In short, the mighty US services sector just disappeared in the space of four weeks. It's gone.

That doesn't mean it's not coming back, but for the duration of the lockdown, it basically doesn't exist.

The unemployment rate, which, as of last month, was parked at a five-decade nadir, may well spike to 20% or higher.

When I asked Nicci what she was doing up so early, she had a simple answer: "Stress-watching Ferris Bueller's Day Off."

III) Déjà vu

On February 2, I regaled readers with a vivid, gritty account of where I was "when the world didn't end" in 2008.

It would be ludicrous for me to suggest that story was a veiled prediction of what, just three weeks later, would morph into a crisis far worse than the GFC.

And yet, parts of it do come across as prescient. For example, I noted that at the time, some of the biggest names in the business were busy declaring that the boom-bust cycle was over.

Bridgewater's Co-CIO Bob Prince, for example, said as much in Davos during an interview with Bloomberg.

"He may be right," I said. "But he may be wrong, too."

I went on to echo the same points made above about the extent to which creative destruction isn't a viable option in modernity. Here are a few passages from that post:

The vestiges of crises past always linger – creative destruction isn’t a viable option in the modern world.

The idea of letting it all burn to the ground in order to ensure that every, last bit of misallocated capital is purged is, at best, implausible. At worst, it’s madness.

But we should recognize that in the absence of that, future crises will be i) inextricably linked to their predecessors, and ii) likely more spectacular than those that came before.

A defining feature of a fiat regime is a rolling boom-bust cycle that snowballs with each turn, which means that policy responses will need to grow in magnitude over time to keep pace with ever larger busts. Eventually, the busts become so large that the policy responses required to combat them become caricatures of themselves that border on absurdity.

Suffice to say that while nearly everyone recognizes that we have no choice but to pull every monetary and fiscal lever at our disposal to offset the measures needed to combat the pandemic, many market participants are still keen to point out that the scope of the rescue efforts are cartoonish.

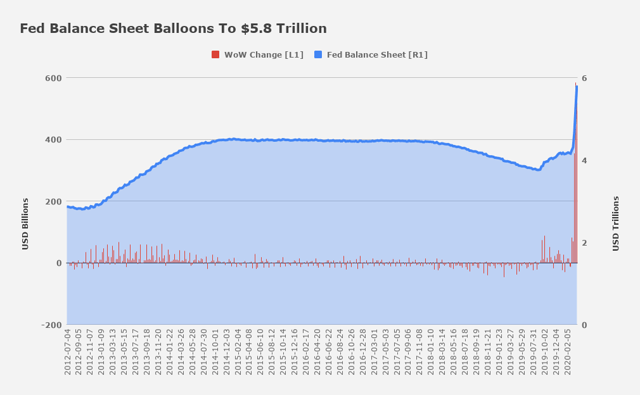

The Fed's balance sheet has ballooned to nearly $6 trillion over the past two weeks, on its way to nobody knows where. And I mean that literally - we don't know how large it will get, and that's one reason why exempting Treasurys and deposits from the supplementary leverage ratio is necessary (there's an explainer from Bloomberg here, which is much more concise than my hopelessly opaque explanation of the same dynamic published elsewhere).

When it comes to equities in all of this, it's admittedly quite different from 2008 when it comes to making the decision to simply keep buying incrementally on down days, on the assumption that the even if there's another leg lower, it can't possibly get that much worse.

There is no analogous historical episode where the entire global economy was simultaneously subjected to an engineered shutdown. As I put it on Friday afternoon, it’s hard to invest in an environment where, for many firms, it is literally impossible to generate operating income by virtue of decrees mandating that businesses cannot operate. You can’t base an investment thesis on earnings because as things currently stand, it’s possible there won't be any earnings for lots of businesses, at least over the next month (or even two months).

One is reminded of the classic moment from Groundhog Day when Bill Murray's Phil Connors is on the phone trying to get information about a blizzard that strands him in Punxsutawney.

When the man on the other end of the line tells him "tomorrow," Phil responds: "Well what if there is no tomorrow?

There wasn't one today!"

Take, for example, the discrepancy between companies which have and haven't withdrawn or altered their guidance.

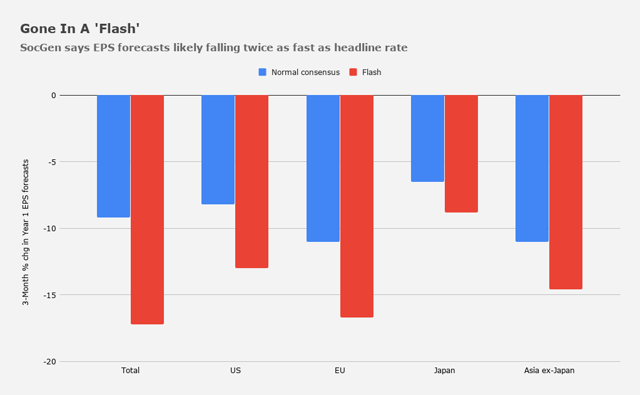

SocGen’s Andrew Lapthorne notes that consensus estimates for corporate profits are likely being artificially inflated by the fact that only some companies have issued updated forecasts to reflect the new, stark economic reality. That, in turn, means EPS estimates are probably falling “at twice the headline rate," he wrote, on Monday.

What would happen if one were to leave out those corporates that have yet to change their guidance?

Lapthorne is glad you’re curious. “Removing these stale forecasts and focusing only on estimates posted during the past 20 days (so-called 'flash' estimates) gives a more up-to-date picture," he says, adding that “globally, instead of Year 1 forecasts cut by 9.2%, so far this year, the flash estimate shows a 17.2% cut, a massive 800bp difference moving the Global 2020 P/E we calculate using the standard consensus from 14.6x to 16.1x."

The upshot is that even with the latest rout, stocks may still be too “rich.” Indeed, 16.1x would, depending on who you ask, represent a fully-valued market during normal times. These are not normal times.

To be brutally honest, there is absolutely no way to know what earnings are going to look like for the second and third quarters. I cannot remember (or find anyone who can remember) a time when there's been less visibility into the outlook for all corporate profits, not just one or two troubled sectors.

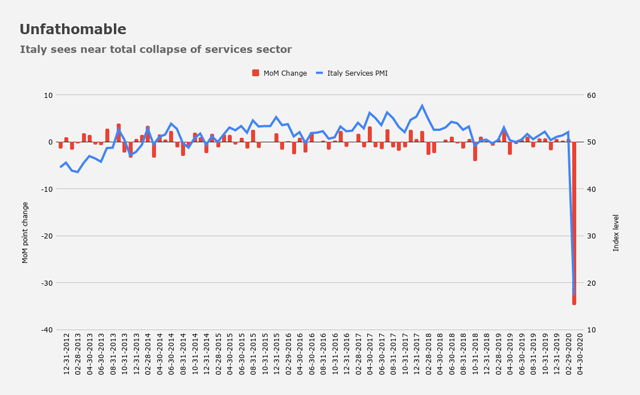

Do you want to see something incredible?

Have a look at the final read on IHS Markit's services sector PMI for Italy:

Show me someone who thinks they can price equities in this environment and I'll show you a liar. It's just that simple.

And yet, maybe there's no need to think too hard about it. Two months ago, reflecting on 2008, I wrote that the trick after Lehman wasn’t so much being “smart” or hewing to some amorphous Buffett aphorism about being “greedy when others are fearful.” Rather, you had to view the situation as binary – either the world was ending or it wasn’t.

Of course, that was a bit of an exaggeration. We often talk about the days following Lehman in those terms and until 2020, that made sense. Now, though, we really are facing an existential crisis. That makes it much more difficult to say, with any degree of certainty, that "40% peak to trough" is as far as it will go, for example.

I suppose it's important to remember that as bad as things are, COVID-19 isn't Ebola or Marburg. And trillions in stimulus won't simply be pulled back once the virus is under control.

The Fed isn’t going to cancel all of the various liquidity facilities and asset purchase programs put into place over the past four weeks if the spread of the virus slows. That bid (which is now unlimited in scope) will be in the market for the foreseeable future, and now it includes spread products.

Similarly, fiscal stimulus measures are being implemented rapidly. Once that money is spent, it’s spent, colloquially speaking. You can’t take the stimulus checks away from people, and you can’t repeal a bill aimed at combating a deadly virus.

IV) Epilogue

Here on the island, not much has changed. Containment "protocol," to the extent it exists here, is barely perceptible even if you're looking for it. There were some half-hearted efforts to put orange traffic cones in front of paths to public beaches, but people just walked around them.

Eventually, the cones disappeared.

Jack is fine, and so are his Porsches. As of this week, he has two parked in the driveway, each of which has a different vanity tag, but I'll refrain from disclosing them.

The local gym is closed, though, so I've taken to running again, despite the protestations of my right knee.

On Friday afternoon, a neighbor I know only as the husband of Martha (an extremely affable retiree I sometimes speak to on her evening strolls) flagged me down as I jogged.

In a previous life, he was a government bond trader and has the stories to prove it. (And I really do mean that - even in his eighties, he still talks as though he's on the desk, lingo, accent and all.)

"What are you telling your readers?," he asked. Earlier this year, Martha asked me to write down the name of the online portals where I comment so she could give it to her husband.

"Well, it's tough," I ventured.

"Ehhh," he waved his hand in apparent disgust. "There's no people. You gotta have this" - he made a "V" with his fore and middle fingers, pointed at his own eyes, then to me. He doesn't care for algos or the idea of them being involved in market making.

We chatted for a while. All three times I've talked with him he's claimed to know nothing about the proliferation of high-frequency trading and the extent to which it's paramount in Treasury market liquidity provision.

And yet, it's always abundantly clear that he accidentally knows more about it than I do. And certainly not because he's steeped in the evolution of modern market structure.

Rather, because his entire existence on this planet has been defined by the government bond market from the time he was a young man until the moment he walked out the shop door into retirement. He knows government bonds. He speaks government bonds. In some sense, he is government bonds.

The whole time we talked on Friday he stayed in his chair, rocking precariously back and forth ("precariously" because it was most assuredly not a rocking chair). He crossed and uncrossed his legs whenever he wanted to make a point.

I asked him if he could remember any period when an exogenous shock with no initial connection whatsoever to markets had such a profound impact on assets.

"Let me tell you something," he said, suddenly adopting an aggressive cadence. "You read the finance page, whatever," he ruffled the copy of The New York Times in his lap for effect.

"But it's what's right here that matters," he insisted, flipping back to the front page and tapping on the section above the fold with his fingers hard enough so I could hear it. "It's what's going on in the world that's gonna move your positions."

I nodded.

"Don't you forget that," he said.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario