When Black Swans Collide

by: The Heisenberg

Summary

- This week will be enshrined in the textbooks as one of the most dramatic stretches in modern market history.

- Understandably, everyone with even a passing interest in finance feels compelled to weigh in.

- Here is a Heisenberg explainer that touches on (almost) every important aspect of a truly breathtaking episode.

- Understandably, everyone with even a passing interest in finance feels compelled to weigh in.

- Here is a Heisenberg explainer that touches on (almost) every important aspect of a truly breathtaking episode.

At some point on Friday evening, after declaring a national emergency in a bid to allay widespread concerns that the federal government is behind the curve in preparing for a public health crisis, Donald Trump sat down, pulled out a Sharpie, and autographed a copy of an intraday Dow chart.

He then sent it to Fox News host Lou Dobbs.

It's true that US equities finished the week with a bang, but to say it's too early to celebrate would be an early candidate for understatement of the year.

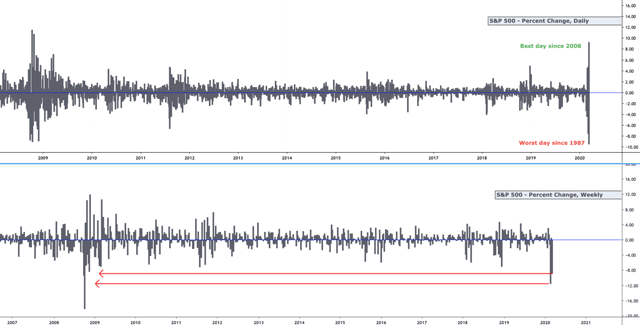

Consider that even after Friday's 9.3% rally (the largest one-day gain since the crisis years), US stocks still had their second worst week since the GFC. I probably don't need to tell you this, but the worst week for US equities since 2008 was the week before last. And, of course, the worst single-session since the 1987 crash came on Thursday.

As I put it Friday evening, "it says a lot about the week when a 9.3% Friday gain still leaves you with the second-worst week since the GFC."

These last five days represent the collision of two black swans, the coronavirus pandemic and an oil price war between Riyadh and Moscow.

That characterization (two black swans splashing down simultaneously and then colliding while swimming in the same pond) is underscored by some of the multi-standard-deviation moves witnessed this week.

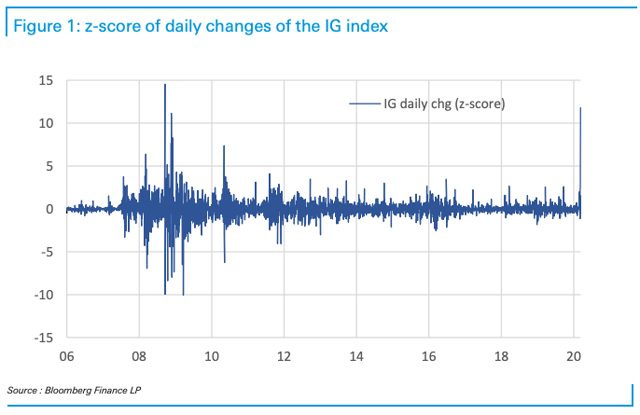

Monday's change in CDX.IG (think of it as the "fear gauge" for US investment grade credit) was a 12-sigma event, for example. That widening is "contested only by the first day’s reaction to Lehman default (16-Sep-2008)," Deutsche Bank's Aleksandar Kocic wrote in a Wednesday note.

Credit spreads ballooned wider this week, in recognition of rising recession odds, rekindling concerns about “fallen angel” risk in BBBs and exposing over-leveraged balance sheets to the biggest stress test since the crisis.

"The epicenter of new risk opened by the oil shock resides in credit," Deutsche's Kocic went on to remark, adding that "behind this reaction of credit lies the decomposition of the IG sector [where] BBB is the largest tranche accounting for about 40% of the entire investment grade universe."

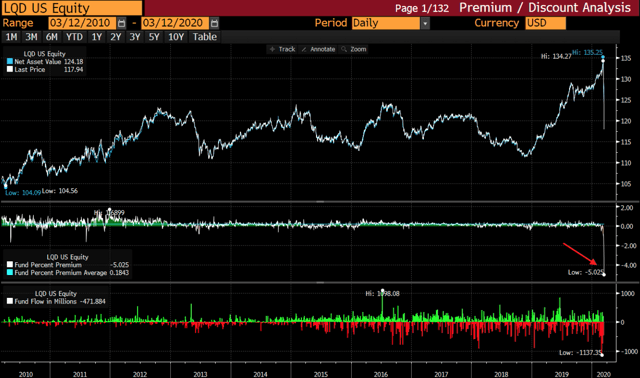

You should note that over the course of the week, bond and credit ETFs showed signs of stress.

Have a look, for example, at an NAV premium/discount analysis for the iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF (LQD):

This is what I (and plenty of others) have warned about for years. Namely that, in a real pinch (where "real" means an actual crisis, not just a period of acute stress), some fixed income products could effectively break.

Bloomberg reluctantly covered this in an article dated Thursday (I'm employing some artistic license using the word "reluctantly" there, but the fact is, nobody wants to admit that the ETFs can "snap," so to speak). Here's an excerpt from Bloomberg's piece:

"The historic volatility roiling American bond markets has created unprecedented dislocations in the ETFs that track them. But the market makers who normally step in to repair price inconsistencies, pocketing a virtually risk-free profit, are cautious. That’s because their standard process has become significantly more complicated with many of their usual price gauges are out of whack."

These products promise intraday liquidity against a pool of underlying assets that are inherently less liquid. Over the years, I've repeatedly described that promise as "a philosophical impossibility."

The arbitrage mechanism that makes it possible on a daily basis will not work in a crisis, and due to the onerous post-GFC regulatory regime, the Street will not be willing to lend its balance sheet in a pinch.

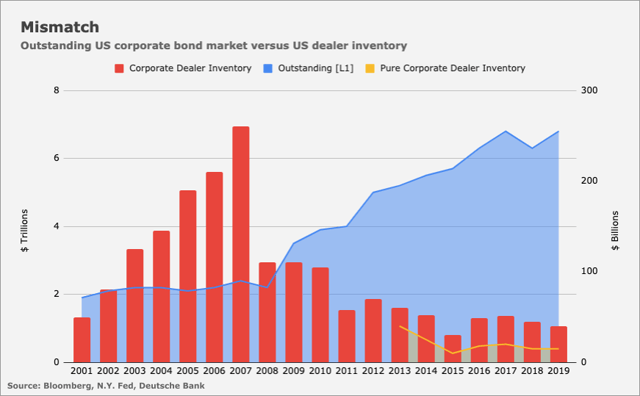

This is complicated immeasurably by the fact that years of artificially suppressed borrowing costs have encouraged corporates to issue obscene amounts of debt, the proceeds from which are in some cases funneled into share buybacks, in a loop that drives stocks inexorably higher, but leaves the corporate sector over-leveraged.

In addition to all the normal concerns about too much leverage, the situation is made more precarious still by the disconnect between the mountain of outstanding corporate debt and Wall Street's capacity to warehouse it.

Here's a visualization:

The setup described above simply cannot work in a crisis or a firesale scenario.

As I've repeatedly stressed when discussing this since 2016 (and long before that in my "pre-Heisenberg" existence), I am not making a "doomsday" prediction or otherwise suggesting that anyone sell anything (or buy anything to hedge against a credit apocalypse).

All I am saying (and all I have ever said on this subject) is that the whole setup is based on liquidity transformation. The only kind of liquidity transformation that "works" infallibly is fractional reserve banking in countries where the government guarantees deposits.

Any other kind of liquidity transformation is philosophically impossible. Although it can be mitigated by a variety of intervening mechanisms (one of which has been severely constricted for years as shown in the chart), it will cease to function in a true crisis absent a government guarantee. Period.

That is (quite literally) all there is to this discussion, which is why I quit having it years ago. It's not debatable. Anyone who tells you different is telling you the sky isn't blue. They are right on cloudy days, but ultimately, they are wrong. Here's Bloomberg to explain what happened this week (from the same article linked above):

"It’s not uncommon for an ETF to drop below its net-asset value -- but it is unusual to see a continuation of that. In normal market environments, such a decline presents an arbitrage opportunity for certain middlemen known as authorized participants.

Typically market markers will buy shares of the ETF as its price drops and redeem these shares with the issuer in return for the underlying bonds. The authorized participant will then sell those securities to capture a relatively risk-free profit. By reducing the supply of ETF shares, the fund’s price typically returns to tracking the fund’s net asset value.

But as the coronavirus outbreak unleashes historical turbulence in financial markets and liquidity dries up, ETFs spanning the bond spectrum are trading at steep discounts. That dynamic will likely persist until volatility subsides and market makers have a better sense of where they can sell the underlying debt, according to UBS Global Wealth Management’s David Perlman."

I want to make an absolutely crucial point here which I also drove home on Twitter during a brief exchange with Bloomberg's ETF expert. None of the above is to suggest that anyone in the industry is doing anything "wrong" by offering these products.

They are absolutely safe in almost any market environment imaginable outside of a true meltdown, and these vehicles (the "normal" ones, that is - I'm not talking about levered products) will likely make it out of this pinch just fine.

So, please, before anyone criticizes me for being a fixed income ETF doomsayer, at least acknowledge that latter paragraph.

But it wasn't just credit ETFs. It was also bond ETFs. I'm not sure how many readers here are aware of this, but the Treasury market effectively stopped functioning this week. That's a gross oversimplification, but suffice to say that disconnects between cash versus futures and myriad dislocations showed up on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, setting off a near incessant stream of chatter about basis widening and what were almost surely all manner of RV blowups.

"20bps+ swings [are] now becoming standard, particularly within the off-the-run space which are trading miles wide due to balance sheet dynamics, with no more dealer capacity and RV guys unwinding into clear stop-out trades," Nomura's Charlie McElligott wrote Thursday.

“Relative value — historically a very profitable, highly leveraged strategy — relationships have frayed to the point of incredulity, indicating high levels of distress,” Bloomberg's Cameron Crise said, during a long series of posts. "You don’t need to know what an invoice spread is… to see that the relationship between the long bond and ultras has gone badly, badly awry," he added.

This is one of the reasons the Fed stepped in on Thursday with a "bazooka," in the form of massive new repos and an announcement that the $60 billion/month in purchases aimed at restoring excess reserves would no longer be confined to T-Bills. Friday found the Fed buying across the curve. That's what the New York Fed meant Friday, when they said, in a statement, that purchases were being made "to address temporary disruptions in the market for Treasury securities."

Fed liquidity actions “were introduced in an attempt to offset the obvious liquidity strains in the ‘frozen’ Rates space, as evidenced by the moves in basis/off-the-runs this week,” McElligott said, adding that in order to mitigate the situation further and otherwise allay concerns, the Fed may well expand QE next week. Note that as of Thursday's announcement that purchases will no longer be confined to T-Bills, we are now back in QE in the United States. They're buying coupons.

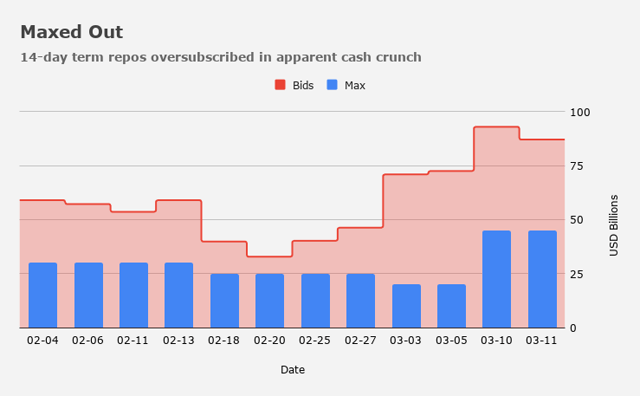

As for the repos, there's a dollar-funding squeeze afoot, which manifested this week in further widening in FRA/OIS and cross-currency basis. The Fed upsized repos twice during the first half of the week, once on Monday as global markets melted down amid the oil shock, and then again in Wednesday's schedule.

That was prior to firing the bazooka on Thursday. That morning (Thursday morning) both the Fed's 14-day operation and the newly added one-month action were oversubscribed. Every 14-day term operation since last month has been oversubscribed.

Do note that in addition to all of this, Treasurys also likely came under pressure from selling to cover losses in other assets (as did gold, which plunged on the week as positions were liquidated to meet margin calls in risk assets).

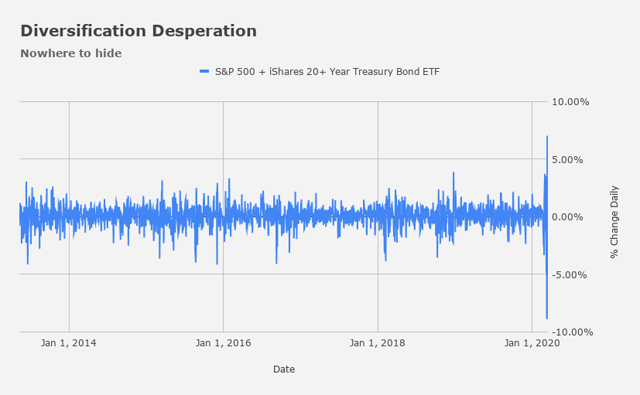

Simultaneous declines in bonds and stocks on Wednesday, and only meager gains for the latter during Thursday's equity rout, led to two consecutive sessions of massive losses for a simple portfolio holding the S&P and (TLT). Friday found such a portfolio rebounding sharply as the gains in equities offset losses in bonds.

That, in turn, brings up risk parity.

In the pair of posts I managed to pen for readers on this platform amid the chaos, I outlined the role played by CTAs, option hedging (gamma) and vol.-targeting funds in exacerbating the rout.

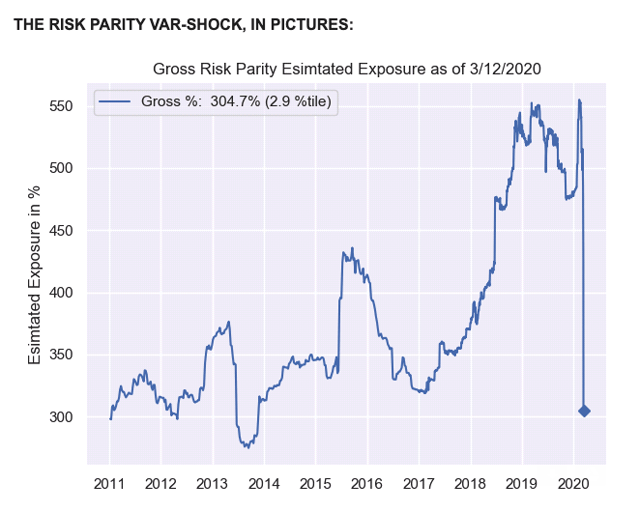

Well, on Thursday, the risk parity kraken was finally released.

Bloomberg ran an article on this around lunchtime Thursday, but by then the genie was out of the bottle. The horse had left the barn. The ship had sailed.

Nomura’s model estimates aggregated gross exposure was cut "from 450% down to 305%" during the session or, from the 61st %ile to just the 2.9%ile (going back to 2011).

In the simplest possible terms, this is just another manifestation of the same "we're all momentum traders now" dynamic I've been so keen on emphasizing for the last couple of years.

These VaR shocks are catastrophic after a decade during which suppressed cross-asset volatility allowed for ever more leverage to be deployed across various asset classes. Some model-based, systematic deleveraging is faster-moving than others (e.g., trend/momentum strats impact the market rapidly, while vol.-targeting and risk parity deleverage on a delay as trailing realized gets pulled higher), but the bottom line for everyday, fundamental/ discretionary investors is this: Now you understand why this ostensible quant-ish "arcana" matters.

Going forward, one thing is certain: The coronavirus news will continue to dominate the tape.

As Pepperstone Group’s Chris Weston remarked, shortly after Trump's ill-fated Oval Office address on Wednesday evening, "investors will not hesitate to show what they think to the Fed and governments" when it comes to the perceived adequacy of the monetary and fiscal policy response.

The US economy is probably headed for a recession - even if it proves shallow. You should note that contrary to some headlines I've seen, Wall Street was not totally behind the curve on this. Deutsche Bank called for a global recession and a bear market on March 2.

Since November, SocGen's base case has been a US recession in Q2/Q3 2020. BNP's base case for the US economy in 2020 (outlined more than four months ago) was the furthest thing from ebullient. Nomura has been exceptionally cautious nearly from the very first headlines out of China about COVID-19. And I could go on.

The point is: Suggesting that Wall Street economists and analysts have totally missed the boat on how the virus would impact the global economy or suggesting that no Wall Street bank predicted a US recession in 2020 are manifestly false claims.

And I don't need to rely on my interpretation of mainstream media articles to say that. I have the original notes, with the timestamps including the day, hour, and minute (literally) that the notes were distributed. Those are the facts. Anything else you read is speculation.

The Fed will likely cut rates by 100bps next week. In my opinion, they'll probably up monthly asset purchases as well. Between the existing $60 billion/month for "reserve management" (and you can just toss that talking point out the window now), reinvestments and, let's just call it another $50 billion on top (that would be a nice round number for the Fed to add), we could see the Fed buying in excess of $120 billion/month in assets going forward, with rates basically back at the lower bound.

So, if you were wondering what happens when two black swans collide, the answer is: "All of the above."

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario