WHAT THE HOUTHIS WANT IN YEMEN´S CIVIL WAR / GEOPOLITICAL FUTURES

What the Houthis Want in Yemen’s Civil War

By: Hilal Khashan

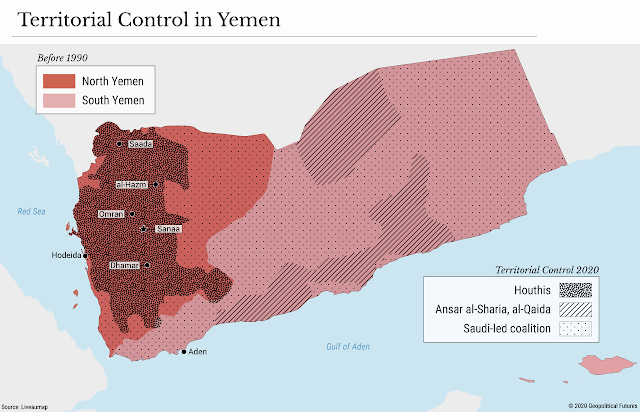

In March 2015, Saudi Arabia launched Operation Firmness Storm against the Houthi rebels, who had taken control of large swathes of territory in Yemen. Five years later, on March 1, 2020, the Houthis scored a significant victory, capturing al-Hazm (which, ironically, means “firmness” in Arabic), the capital of al-Jawf province, which shares a border with Saudi Arabia. The move demonstrated that the Houthis are still determined to keep Yemen’s protracted civil war going, half a decade after it began.

History of the Houthis

The Houthis derived their name from Hussein Badreddine al-Houthi, who, in 1992, founded a group called Harakat Ansarullah (meaning “partisans of Allah”) to promote the interests of the Zaydis, an impoverished and marginalized minority group in Yemen. He began his political career by joining al-Haqq Party, or the Party of Truth, which formed in 1990 to counter the Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated al-Islah Party.

Two years after the Yemeni army killed al-Houthi in 2004, his brother, Abdulmalik, assumed the top post in Harakat Ansarullah, which then rebranded itself as the Houthi movement.

The Zaydis are part of the Zaydism sect of Shiite Islam, but they are closer to Sunni Islam than the Shiite Twelver Imami sect that dominates in Iran and Iraq. They live in the Saada Mountains in northwestern Yemen and account for at least 30 percent of the country’s population. In 1962, a republican military coup put an end to Zaydi monarchical rule in Yemen, which had lasted for 11 centuries, leading to the Zaydis’ marginalization.

Their subsequent slide into impoverishment was the foundation of the Houthi movement before it developed into a political-military group after the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s alliance with the Salafi movement and accommodation of the al-Islah Party soured his relations with the Houthis. And after refusing to surrender the donations their supporters had given to them, the Houthis began clashing with the Yemeni army in 2004.

Many were surprised when the Houthis managed to seize the Yemeni capital of Sanaa in September 2014. Just two months earlier, and with the tacit support of President Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi’s army, they had also captured Omran, a bastion of support for al-Islah.

But given Yemen’s fragmented tribal allegiances, the Houthis needed more than Hadi’s backing to maintain control over these areas. Even though the Houthis had fought six wars against Saleh’s military forces from 2004 to 2010, the two sides became allies in 2014.

Saleh still wielded substantial influence over many army units, including the elite Republican Guard. The new alliance facilitated the Houthis’ conquest of most of northern Yemen. But both Saleh and the Houthis were alarmed at the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood in the wake of the Arab uprisings, especially in Egypt and Tunisia.

The Saudis and Emiratis expressed similar apprehensions about al-Islah in Yemen and, viewing the Houthis as a lesser evil, privately supported the Houthis instead. Thus, Houthi official Saleh Habra flew to London to meet with Bandar bin Sultan, the Saudi secretary-general of the National Security Council, to discuss ways to stop al-Islah.

And the UAE gave the Houthis, through the Dubai-based son of Ali Abdullah Saleh, $1 billion to cover the cost of their military drive against al-Islah in Omran and Sanaa. Publicly, however, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi expressed concern over the fall of Sanaa to the Houthis. Saudi preacher Abdulaziz al-Tarefe even issued a proclamation that considered jihad against the Houthis a sacred duty.

The religiously driven, organized and well-structured Houthis eventually took over northern Yemen from Saleh and his party, the General People’s Congress. They also took advantage of Hadi’s cooperation with Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi’s desire to see South Yemen become an independent state.

The Houthis have insisted on the implementation of an agreement that came out of the National Dialogue Conference in 2014, even though it did not specifically address their grievances relating to the Zaydis or those of the Southern Movement. They have also dismissed the Saudi claim that they are a Trojan horse for Iran, which supplies them with cash, light weapons, missile components and technical assistance. Iran’s relationship with the Houthis is fundamentally different from its relationship with Hezbollah.

The Lebanese party is ideologically committed to the principles of the Iranian Revolution and its supreme leader. The Houthis, on the other hand, are more independent, though they have adopted their own version of some of the fiery proclamations of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, such as the group’s slogan “Allah is Greater, death to Israel, death to America, curse on the Jews, victory to Islam.”

The Saudis’ Role

In 2009, the Houthis challenged the Saudis directly, capturing al-Dukhan Mountain in Saudi Arabia’s Jizan region and some 50 villages, after King Abdullah allowed the Yemeni army to attack the Houthis in Saada from Saudi territory. Since then, the Saudis have refused to accept that they have lost the influence they once had in Yemen and, beginning in March 2015, have waged war against the Houthis to reestablish their once powerful position in the country.

Houthi assurances that they would not allow penetration of Saudi territory from Houthi-controlled areas if the Saudis do not interfere in Yemen’s domestic affairs have not deterred the Saudis from engaging in the civil war, even though they were ill-prepared for it. (Despite massive military spending, the Saudi armed forces do not have a combat doctrine or army creed.)

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman reasoned that the Saudi armed forces’ sophisticated arsenal would easily and swiftly force the Houthis to capitulate, allowing Riyadh to reestablish hegemony in Yemen.

But things did not play out quite as the Saudis hoped. The Yemeni army has failed to retake Sanaa, and the Saudi-UAE coalition has effectively collapsed. (The UAE pulled its troops out of Yemen and is now focused on securing its interests with the southern secessionist movement.)

The once-ruling General People’s Congress did not sever its ties to the Houthis after they assassinated Saleh in 2017. And the Saudis have failed to pull al-Islah back to their side, after they betrayed the group in 2014. Riyadh therefore has no allies left in Yemen.

Many Yemenis continue to argue that the Saudis hold a grudge against Yemen and want to keep the country weak. As evidence, they point to Saudi agents’ 1977 assassination of Yemeni President Ibrahim al-Hamdi – in an operation strikingly similar to Jamal Khashoggi’s killing – because he refused to provoke an armed conflict with the communist government of South Yemen.

The mutual distrust between the Saudis and Yemenis, as well as the absence of a force capable of stopping the group, has enabled the Houthis to continue pursuing their strategic objectives in the civil war.

The Houthis’ Objectives

Which raises a question: What exactly are the Houthis’ strategic objectives in Yemen?

Their main objective is to keep the war going until they can dominate the country. They want to play a decisive role in Yemeni politics as per the Peace and National Partnership Agreement that they reached with Hadi’s government right after they took over Sanaa, which received the blessing of the Gulf Cooperation Council and the U.N. secretary-general.

The agreement called for the formation of a technocratic Cabinet, headed by a politically neutral prime minister, and the appointment of two advisers to the president, one Houthi and another from the Aden-based Southern Movement. The Houthis also want to control some of Yemen’s political institutions, especially the office of the prosecutor general, central control and accounting apparatus, and the departments of national and political security.

The Houthis reject Yemen’s republican order and consider it a consequence of the 1962 coup that ended Zaydist rule, which they want to reestablish. They objected to the Saudi-proposed GCC initiative to end the 2011 uprising because it preserved the former regime.

They also had serious issues with the National Dialogue Conference’s proposal to turn Yemen into a federation consisting of six regions because it favored Saudi Arabia. It would have given the Houthis control over landlocked Azal region, which includes Saada, Omran, Sanaa and Dhamar, but allocated nearby oil-rich areas to Saudi allies in Saba.

With no end in sight, the conflict in Yemen has turned into a war of attrition that is severely draining Saudi resources and hampering Riyadh’s Vision 2030 project to modernize the kingdom. The Houthis are playing the long game – a game in which they believe they will eventually prevail.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario