By: Allison Fedirka

In a development that would have been unheard of just a few years ago, the government in Caracas is slowly and quietly loosening its control over the Venezuelan economy. Markets are opening, regulations are being relaxed, and foreign countries are participating in its flailing state oil company.

Various Venezuelan media have dubbed this unexpected period of transition “wild capitalism” and “chaotic capitalism,” but whichever name sticks, the strategy of the government is clear: adapt or die.

It’s a fairly pragmatic response to the actions of the U.S., which hoped that economic pressure, widespread public protests and international support would bring an end to the Maduro administration. Instead, Caracas has simply become more creative and resourceful as it seeks to remain in power – this time by integrating its informal economy with its formal one.

Economic Pressure

For nearly 20 years, the United States has opposed the Venezuelan government on political and security grounds. But Washington grew more impatient as the Venezuelan economy tanked, thanks largely to low oil prices, high social welfare spending and economic mismanagement.

The social instability that followed was a perfect opportunity for the U.S. to tackle what it saw as a security threat head on to try to facilitate regime change. It employed a strategy of heavy economic pressure for three reasons.

First, U.S. military intervention in Latin America is risky, unpopular and historically counterproductive. Second, the strategy corresponds with a broader shift in national strategy away from military action as the force to bring about change. Third, the U.S. is the largest economy in the world and formerly Venezuela’s single biggest customer, so changes in trade patterns would disrupt the Venezuelan economy.

Initially, things went according to plan. Increasingly heavy sanctions aggravated the underlying weaknesses of the country’s economy. Working conditions and quality of life went from bad to worse for the vast majority of Venezuelans as hyperinflation, power outages and food shortages became commonplace.

The economy has contracted for the past six years, losing roughly two-thirds of its gross domestic product from 2013 to 2019, according to the International Monetary Fund. Projections for 2020 remain bleak as GDP is expected to contract by another 10 percent.

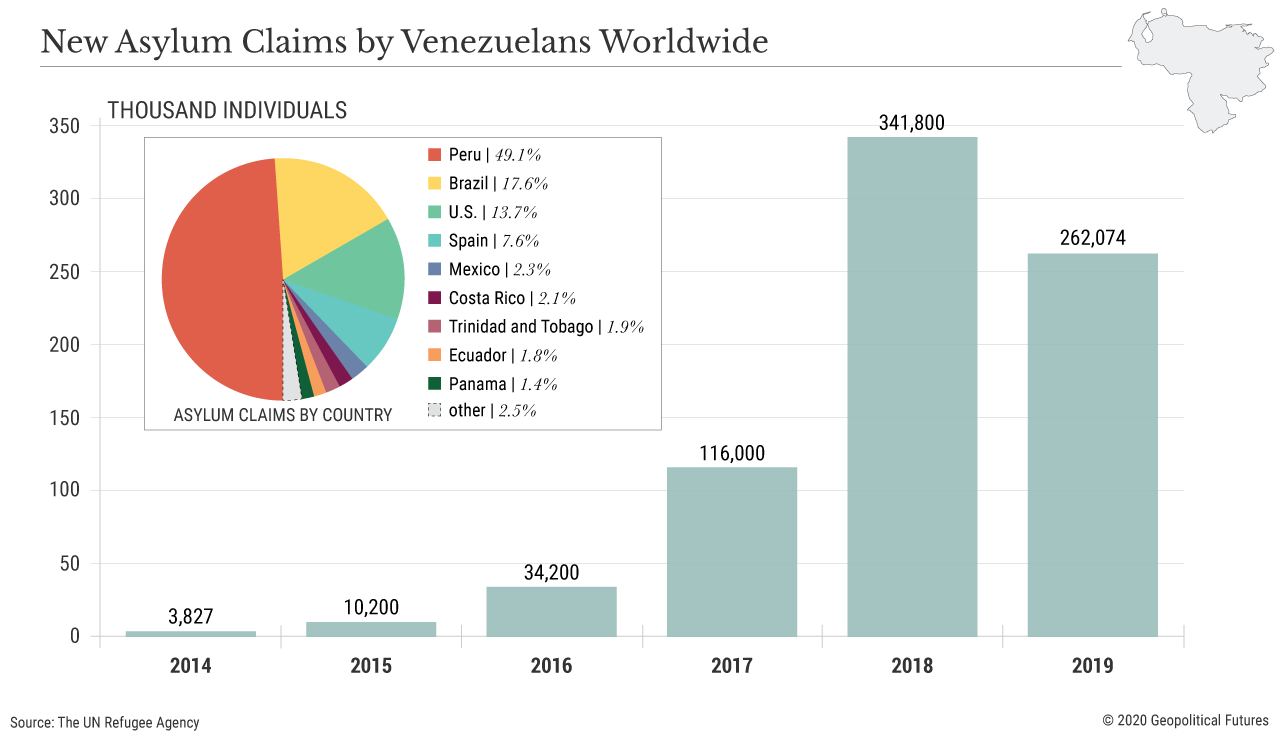

Emigration – particularly among oil industry experts – was a problem even during the Chavez administration, but economic decay over the past two years has accelerated the trend. As of this year, an estimated 4.7 million people – out of a population of 28.4 million – have fled the country.

Washington also enacted a political strategy of supporting Maduro’s enemies to capitalize on public discontent and usher in a new government, culminating with Juan Guaido, the president of the opposition-led National Assembly, declaring himself the president in 2019. For a brief moment, it seemed that pressures were aligning such that the U.S. would deliver the intended results.

Except it didn’t. Economic restrictions and lack of availability of goods expanded a robust parallel market that became essential for procurement of basic public goods. Before the U.S. levied its sanctions, economic hardship taught Venezuelans the value of acquiring and saving strong foreign currency, namely the U.S. dollar.

Those who could established bank accounts in the U.S. Meanwhile, early expatriate Venezuelans, many of whom were educated and/or wealthy enough to find work abroad, provided a steady flow of U.S. dollars directly to their fellow Venezuelans. Indeed, remittances to Venezuela have risen sharply since 2016, totaling an estimated $3.7 billion-$4 billion in 2019, according to Ecoanalisis. (The increase owes to both the number of transactions and value of transactions.)

According to a Consultores 21 survey, some 40 percent of the population has received remittances at some point in time and another 32 percent receive remittances on a regular basis. When government restrictions made it harder to get or use U.S. dollars, more informal or electronic means were employed to get dollars into the country. This rendered the local bolivar essentially worthless as bartering and foreign currencies have become the preferred choice for commercial transactions.

Rather than fight the dollarization of the economy, the Maduro government embraced it. It relented on some currency controls and allowed a freer circulation of dollars because doing so would help to normalize the economy.

After all, a recent Ecoanalitica report estimated that over half of the country’s transactions occur in U.S. dollars and that there are likely more dollars circulating in the country than bolivares. Changes in fiscal policy now allow for some purchases of foreign currency with a 25 percent value-added tax.

This allows for fees and goods to be purchased and sold in foreign currency on a larger scale, making them more accessible to those with foreign currency. Businesses have also resorted to dollar-denominated transactions.

Over the past few months, banks have begun to offer custodial services for holding billions of U.S. dollars and euros in cash for businesses that want to avoid ties with the government and thus evade sanctions. This may not be much help to those without access to dollars, but it has lowered inflation in the dollar-denominated economy while giving more access to more people for basic goods.

The Maduro government has eased off other areas of the economy too. It has let imports in and lifted restrictions on certain exports. Goods can now be shipped out of Cabello Port in Carabobo without the requisite red tape. Price controls have also been lifted on many goods, and companies have been allowed to invest what small funds they have.

But the most notable changes pertain to state-run oil company PDVSA. The lack of funds to repair dilapidated equipment, improve production and support business operations like refining has led PDVSA to look for support from foreign oil players, particularly Rosneft, to conduct its business. The government is also in talks with Spain’s Repsol and Italy’s ENI on how to partner or take a share in the company in exchange for capital and assistance in a scheme of virtual privatization.

Saving Face

All these measures demand a certain political flexibility to mitigate whatever risks they could pose, considering they fly in the face of Maduro’s previous policies. By allowing for reform, he has tacitly admitted that those policies have failed.

Caracas has made sure to sell the changes without losing face. In some cases it downplayed them. In others, such as dollarizing the economy, it simply passively allowed it to happen. The government has also attempted to employ traditional revolutionary rhetoric when publicly speaking of the changes, framing them as measures necessary to help the poor in Venezuela and respond to economic attacks. (The regime’s roots are buried deep in Hugo Chavez’s legacy; echoing him lends Maduro some legitimacy.)

Still, Venezuela is long past the point where it can downplay or ignore its plight. When Maduro opened the judiciary session this year, he acknowledged that the U.S. isn’t entirely to blame for everything wrong in the country – a pretty significant rhetorical departure for him – adding that more work was needed to transform the country. He received a standing ovation.

But Maduro still has to tread carefully. He shares a delicate balance of power with Diosdado Cabello, the head of the Constituent Assembly (the pro-government legislature) and current #2 in the governing PSUV party, and Vladimir Padrino Lopez, the minister of defense. (Economic liberalization would be particularly galling to a dyed-in-the-wool Chavista such as Cabello.) There are also two competing legislatures that would be involved in whatever economic change is made into law.

Which is to say that Maduro’s hold on power is still precarious. “Wild capitalism” hasn’t solved any problems – things are still very expensive, and not everyone benefits from access to foreign currency – and Maduro risks alienating his supporters by seemingly turning his back on the legacy of Chavismo.

This means he is still vulnerable to losing power and opening a path for a more moderate Chavista to step in, rather than someone like Guaido who marked a complete departure from the regime. This is the opposite of what the U.S. had in mind.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario