Investors must put pressure on weak companies when interest rates do not

Robert Armstrong

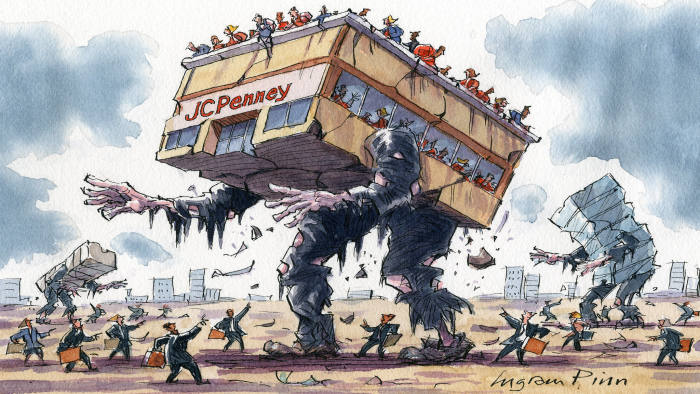

© Ingram Pinn/Financial Times

JC Penney has been stuck for years in permanent twilight, with changes in retail and the weight of its own balance sheet blocking out the sun.

Department stores are relics of the past. Malls, where many of the US chain’s stores sit, are fading too. JC Penney had 1,100 stores a decade ago; now it has 850. Its shares recently slipped under a dollar. For several years, operating profit has not covered the interest on its $5.3bn in leases and debt.

Yet JC Penney staggers on. Economists and occultists have a word for things that walk the earth, dimly aware that they are no longer alive: zombies. After a decade of central banks pushing liquidity into the global economy, there are a lot more of them. And they may be eating the brains of the corporate world.

In a competitive market, some economists warn, the zombies would be at rest in their graves.

Instead they walk abroad, reanimated by cheap money. They depress prices while crowding out productive investment and new entrants. With no JC Penney there would be — in theory — more room for young retailers with new ideas, or for Amazon’s ultra-efficient platform to sell still more for still less.

Across the developed world, according to a study from the Bank for International Settlements, the proportion of listed companies unable to cover their interest costs from operating profit, and with weak growth prospects, doubled from 3 to 6 per cent between 2007 and 2016.

Other studies find a similar trend, especially in Europe, and conclude that zombie companies are associated with lower investment, lower productivity and lower inflation — the opposite of what central bankers aim for.

In 2018, already in dire straits, Penney was able to raise $400m in debt at a coupon of under 9 per cent. It’s hard to imagine that infusion would have been available if US Federal Reserve policy had not left investors desperate for yield. The point is not that JC Penney can avoid bankruptcy forever. It may not, or may yet pull off a turnround. But the Fed has extended the process, as it has for thousands of other companies.

Ryan Banerjee and Boris Hofmann of the BIS point to a trade-off for central banks: they may increase demand with easy money, but only at the cost of misallocated resources. Viral Acharya of New York University says “it is hard not to entertain the thought . . . that Europe is following the path of Japan”, where low rates and banks’ refusal to write off bad debt sapped growth for decades.

The risks of monetary accommodation are usually framed in terms of asset bubbles, but zombies — the bubbles’ dark flipside — may be just as important. Just as low yields on risk-free assets lead to fevered bidding for speculative assets, from WeWork to Tesla, so ample liquidity allows weak companies to push hard choices into the hazy future.

If rates jump, bubbles and zombies will go from being a negative but manageable policy side effect to a pressing threat to stability. The bubbles would burst just as the zombie hordes were forced into a rush of disorganised reorganisations and liquidations.

Rates may remain low and stable forever. Such seems to be the current consensus of the market. But higher rates are a contingency to be prepared for, not least because of the most precious capital zombie companies hold: their staff. Penney has 95,000 employees. They are the living, not the undead.

Policymakers can help by requiring banks to write off loans to companies without a realistic path to profitability. But that might not be enough. Businesses that go through Chapter 11 (in the US) or administration (in the UK) need not disappear, so long as the price of their product is higher than the cost of producing it and the business is worth more in operation than sold for parts.

Many marginal businesses keep operating after a reorganisation, often with the help of yet more cheap financing. JC Penney’s competitor Sears, after years among the undead, declared bankruptcy in 2018. Many of its stores remain open.

Eliminating the tax advantage of debt over equity, and requiring robust unemployment insurance and retraining programmes, would lower the risk and limit the damage. But both would require a political realignment.

In the meantime, it is up to investors to protect their companies from the zombie virus. Activist investors set an example. The German conglomerate Thyssenkrupp, while not a fully fledged zombie, has been lurching in that direction. Operating cash flow barely covered debt service last year.

Activists Cevian and Elliott have come in and pushed for the most profitable division, elevators, to be split off. They may lose their bet; the point is just that they can apply pressure when rates do not. Similarly, the UK’s Punch Taverns, zombified by a debt-funded acquisition spree, was beset by hedge funds. It broke itself up, and agreed to sell a large block of its pubs to Heineken.

Is it too much to hope that more investors, in the days of passive investment and management-controlled boards, will demand that executives make hard choices instead of slipping into zombiehood? We are in trouble if it is.

The most frightening side effect of central bank policy may not be zombie companies, but rather zombie investors.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario