An FT investigation into the complex dealings of the group that helped out the Kushners by leasing 666 Fifth Avenue

Mark Vandevelde in New York

© FT montage / Getty

On a busy stretch of Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue a few blocks south of Trump Tower, a decaying skyscraper stands as a rebuke to the $1.8bn deal that Jared Kushner helped his family sign a decade ago, at the age of 26. It was the most expensive New York office purchase in history, and for a time it looked likely to sink the Kushners’ business. Steve Roth, the billionaire who co-owned 666 Fifth Avenue, lamented it would “be worth a lot more if it was just dirt”.

By 2016, Mr Kushner was searching for a way out. Destined for a top job in his father-in-law’s White House the following year, he found plenty of people to talk to, but no one who was buying. Discussions with Anbang, the Chinese insurance group, came to a halt some time before its flashy chairman Wu Xiaohui landed in a Chinese jail. The Qatari finance minister Ali Shareef al-Emadi met Mr Kushner’s father in 2017, although Charles Kushner has said he took the appointment “out of respect” and stressed there could be no deal.

Then, with months to go before $1.2bn of mortgage payments fell due in February 2019, the Kushners won a reprieve — one that looked nothing like a favour from a foreign state. It was an investment from financial group Brookfield, which leased the building whole, paying nearly a century of rent in advance.

Brookfield is a name that towers over the global investment industry, even if it receives less scrutiny or attention than rivals of similar size. The name adorns the skyscrapers of London’s Canary Wharf, Berlin’s reconstructed Potsdamer Platz and New York, where Brookfield dwarfs every other commercial landlord. And it reaches far beyond real estate; Brookfield’s eclectic investment portfolio includes 14,500km of railways and toll roads, about one-seventh of France’s mobile phone masts and Westinghouse, the formerly bankrupt nuclear reactor maker.

Originally an outgrowth of the Bronfman liquor dynasty, the group today attracts money from ordinary stock market investors, sophisticated public pension systems and sovereign states including Qatar, the gas-rich Middle East state whose finance minister the elder Mr Kushner appeared to spurn. “Our reputation is that if you have a large transaction, if you have a difficult transaction . . . go to Brookfield,” says chief executive Bruce Flatt.

Yet what exactly Brookfield is, and how it operates, is maddeningly difficult to ascertain.

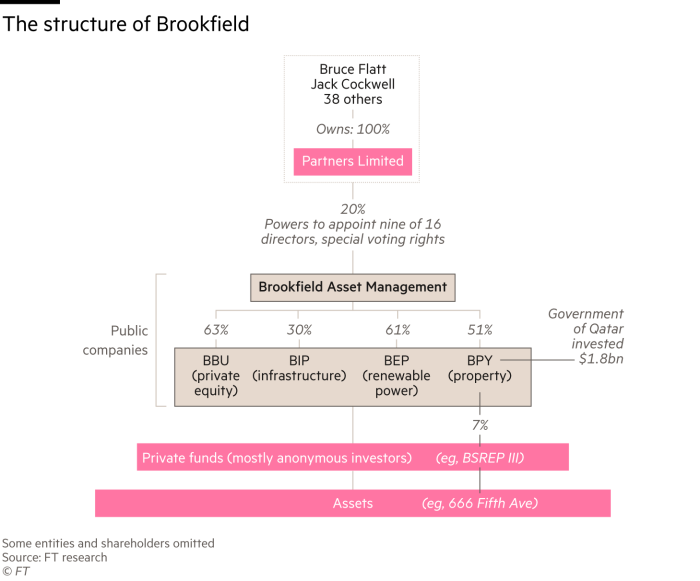

To unpack the Canadian group’s accounts is to discover not so much a company as a giant, triangular jigsaw board that spreads across the world and covers assets worth $500bn. The pieces are hundreds of corporate entities, all locked together by elaborate contracts, which give 40 people at the top the right to rule huge sections of the puzzle almost as if it were their own.

Those insiders wield such power that the companies below them could face risks similar to those of “pyramid control companies”, according to a draft investor disclosure that Brookfield filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2013. (The final version warned instead of risks “associated with a separation of economic interest from control”.)

Jared Kushner and Steve Roth, the billionaire who co-owned 666 Fifth Avenue, which was leased for 100 years by Brookfield Asset Management © Andrew Harnik/AP

Over the past six months, the Financial Times has asked current and former executives, and others who know Brookfield well, to shine a light on this empire. Some refused to talk; others requested anonymity, citing non-disclosure agreements or fear of reprisals.

Even as they spoke, the Toronto-based group pushed further into US finance, completing an acquisition of Oaktree Capital Management, the private equity firm founded by Howard Marks and Bruce Karsh. Yet in interviews, securities filings, litigation records and other documents, a picture emerges of an investment group that defies convention: highly secretive, seemingly obsessed with control and susceptible to family squabbles that have few parallels among its Wall Street peers.

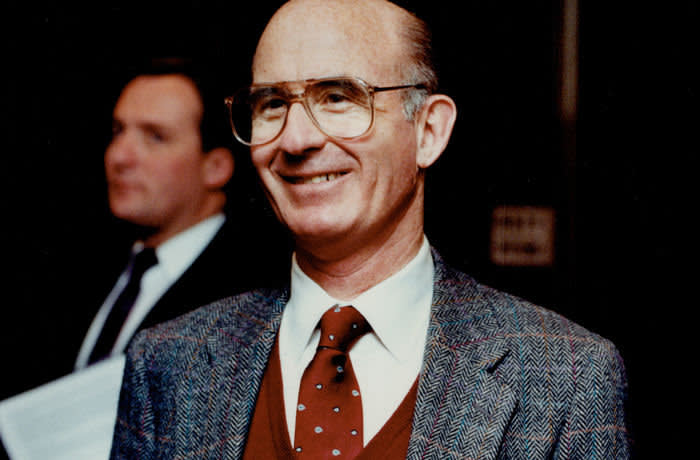

Brookfield began with a $15m inheritance and a family feud. The money came from Samuel Bronfman, founder of the Seagram Company, who made a fortune out of alcohol just as America turned to prohibition. The feud involved his two nephews, Peter and Edward, and it began in 1952, when Samuel locked the young brothers out of Seagram’s offices and forced them to sell their shares for less than they were worth. The key actor, though, was accountant Jack Cockwell, who teamed up with the two brothers, and whose shrewd dealmaking helped build up the group.

A turning point for the Bronfmans came with the acquisition, following a messy takeover battle, of Brascan, the former owner of a Brazilian electrical utility, which was sitting on a pile of cash after the military dictatorship nationalised its biggest asset. In Mr Cockwell’s hands, the New York-listed Brascan became a platform for controlling just about anything: breweries and sports teams, forests and mines, real estate brokers and investment banks.

Bruce Flatt, Brookfield chief executive: 'Our reputation is that if you have a large transaction, if you have a difficult transaction . . . go to Brookfield.' © Christopher Goodney/Bloomberg

By the 1980s, Edward and Peter Bronfman were two of Canada’s richest men. They also presided over one of the world’s most complicated corporate structures, with booty from their acquisition spree split between dozens of public companies and hundreds more private vehicles.

Edward sold his shares in 1989, retired and took up philanthropy. Peter stayed on to orchestrate the deal that would create Brookfield.

At the centre of the transaction was Pagurian Corporation, which was controlled by executives including Mr Cockwell and shared its name with a species of crab that, having no shell of its own, steals the exteriors of dead snails.

In 1993, with real estate values falling and Brascan selling off assets, Peter Bronfman sought an exit. Pagurian ended up with a majority stake in the Bronfman empire, while Peter Bronfman, whose fortune had seeded the vast enterprise, reportedly received about $25m.

Following a series of name changes, mergers and share-swaps that brought together many of the former Bronfman companies, Pagurian is today known as Brookfield Asset Management.

Its leaders have soared in wealth and influence since the departure of the Bronfmans. Mr Cockwell still serves on Brookfield’s board, and holds shares worth about $1.6bn. Mr Flatt, who became chief executive in 2002, has accumulated stock worth another $2.5bn.

Samuel Bronfman, founder of the Seagram whisky company and uncle of Peter and Edward Bronfman © Arthur Schatz/LIFE/Getty

Their position seems secure; BAM shareholders have earned compound annual returns of 18 per cent over the past 25 years. And even if that performance should falter, the two men would be difficult to dislodge, for they own a big piece of a lesser-known company named Partners Limited, which has the power to override the votes of every other Brookfield shareholder.

“In form, Partners is a corporation,” explains a two-page memo sent in the mid-1990s to a handful of Peter Bronfman’s employees, and seen by the FT. In substance, it sounds like something else entirely: a routine of “weekly luncheon meetings” that comes with serious financial perks.

Conceived as a way for executives to “become a financial partner with Mr Bronfman”, Partners today wields enormous power over Brookfield. Its 40 members own about one-fifth of BAM, but have enough votes to appoint nine of its 16 directors. A dual-class structure means they can also overrule shareholder motions even if they are supported by outside shareholders.

The identity of some of those “partners” is not clear. Brookfield named only a handful in its 2018 public filings, although all are said to be current or former Brookfield executives. (Among them are Mr Flatt and Mr Cockwell, who own half of Partners between them, according to Brookfield; another five executives were identified who hold about another third.) Peter Bronfman’s widow Lynda Hamilton, who later married Mr Cockwell, has been named as a shareholder in previous years, as has Mr Cockwell’s brother Ian, who once ran Brookfield’s housebuilding division. (Brookfield says neither currently own Partners shares.)

Mr Flatt likens the system to Goldman Sachs’ former partnership, with insiders promising to forgo most outside business interests, and departing executives ceding their shares to younger partners in exchange for payments stretching over 20 years.

Peter Bronfman with his brother Edward built an enormous conglomerate in the 1980s that formed the basis of Brookfield Asset Management © Tony Bock/Toronto Star/Getty

It is not always harmonious. In one puzzling dispute, a departing executive filed a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against Mr Flatt’s brother Gordon, who has no apparent connection to Brookfield. (The litigation took place in Bermuda and few details are public, but Gordon Flatt denied the allegations against him, and a knowledgeable person said the case had been settled.)

Yet despite an elaborate structure that vests power in insiders, Mr Flatt insists that Brookfield is run by an independent board. “That partnership does nothing,” he says. “We never have meetings, we don’t vote on anything, there is nothing to do. But it has those rights, and they’re very important.”

Two days before Brookfield bought the Kushners’ office tower last August, an executive named Brian Kingston dialled into a conference call with analysts and casually disclosed that his team had just closed a $1.4bn transaction involving a different set of New York properties. Brookfield was the seller. It was also the buyer.

More precisely, the buyer was BAM, which sits a few rows from the top of the Brookfield triangle, and is sometimes known as Brookfield for short. This was already unusual: when the Brookfield group buys an asset, the money usually comes from one of the investment funds it runs for outside investors. “BAM doesn’t do anything,” Mr Flatt confirms. “BAM never puts up any money, for anything. That’s why, if you’ve read any of our materials, we’re increasingly at the point where we generate way more cash than we need.”

Edward Bronfman retired in 1989 and took up philanthropy © Frank Lennon/Toronto Star/Getty

But this time BAM was in fact putting up money, to buy a 28 per cent stake in a bunch of New York office towers. And it was doing more besides. The buildings were owned by Brookfield Property Partners, a separate Nasdaq-listed company that sits further down the triangle, trades under the ticker BPY and — confusingly — is also sometimes known as Brookfield for short. Because BPY does not employ any property specialists, it delegates tasks such as identifying assets to buy and sell to other parts of the Brookfield empire. As well as snapping up the New York office tower stakes, therefore, BAM was steering BPY to get rid of them.

“We very seldom sell between companies,” says Mr Flatt. (Brookfield says that “fiduciary responsibility sits at the centre of everything we do”.) The transaction was vetted by BPY’s independent governance committee, its full board and the board of BAM, Brookfield says, adding that all the directors received extensive information, and a fairness opinion from an independent adviser. BAM told investors in November 2018 that it planned to sell the property interests to outside investors “in the near term”, but more than a year later, it has yet to announce a buyer.

Even today, shareholders know little about why BPY wanted to sell 28 per cent of its core office portfolio for $1.4bn, or why BAM wanted to buy. The rationale was that BPY needed cash.

“The only reason we did that,” Mr Flatt says of the office tower deal, was that “it [BPY] needed some extra capital. And this was an easy way to do it.”

The money was needed, Mr Flatt explains, to pay for a big wager on US shopping malls — a sector that many investors have left for dead. BPY consummated the bet in August 2018 when it merged with retail landlord GGP, whose shareholders received cash payments worth $9.3bn.

Yet that was also the month when some of BPY’s cash was committed to 666 Fifth Avenue, the office lease in midtown Manhattan that is still jangling nerves from Washington DC to Doha.

Ali Shareef al-Emadi, the Qatari finance minister © Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg

The Kushner deal was assembled from several pieces of the Brookfield empire. The lease was signed by a company named BSREP III Nero LLC, a possible allusion to the emperor who was blamed for the burning of Rome. That company is owned by a fund called BSREP III, which is managed by BAM and was, at the time, controlled by BPY — all of which placed the deal where global finance blends into geopolitics on the jigsaw.

The known links between Qatar and Brookfield all converge on the investment group’s listed property fund BPY. About one-tenth of the fund’s assets are tied up in skyscrapers in Canary Wharf and Manhattan that are co-owned by Qatar, but the connection goes further. Through a sovereign wealth fund, Doha is one of BPY’s biggest investors, holding $1.8bn worth of BPY preferred equity. The securities have a debtlike quality, and Qatar can force BAM to buy them back for $1.8bn over the next six years.

In theory, Qatar has significant influence over BPY. It is entitled to choose one person to sit on BPY’s board, and to receive confidential information that other investors never see. Brookfield says Qatar has never exercised either of those rights. (The Qatar Investment Authority declined to comment.) Both sides have previously indicated that, when Brookfield was negotiating the $1.3bn lease on 666 Fifth Avenue, a building that Charles Kushner had discussed with the Qataris in 2017, the emirate was not involved.

No matter who made the decision or knew about it, rescuing the Kushners strikes some real estate investors as ill-advised. “It was widely regarded as a very full price, in a midtown office market that’s challenging, in an asset that’s going to require substantial capex in order to make it leasable,” says a leading dealmaker. Brookfield takes such scepticism almost as a backhanded compliment. “We buy troubled, stressed, things,” says Mr Flatt. “We’re going to reskin the building, and we’re going to fill it up. It’s going to be amazing.”

In the public accounts of BPY, the listed property fund that received Qatari investment, 666 Fifth Avenue has already all but disappeared. Last January, BPY lost control of BSREP III, the private vehicle that owns the building, after reducing its stake to $1bn. New investors piled in, each taking a piece of the Kushner tower, and lifting the private fund’s firepower to $15bn.

That influx of cash has not made the tower’s ownership any more transparent. A handful of US pension funds have acknowledged their participation, but few other investors have been identified publicly. Knowledgeable people insist that no Qatari money is involved. Materials reviewed by the FT show that about $3bn of the total comes from sovereign governments, although they do not specify which ones, and $2bn of it from the Middle East, although the document does not say exactly where.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario