What The Qassem Soleimani Black Swan Means For Markets

by: The Heisenberg

- Just two trading days into 2020, a geopolitical black swan the size of an elephant splashed into the waters of history.

- The assassination of the second-most powerful man in Iran will echo through history, but what does it mean for markets?

- The answer is complicated, but your reaction function need not be.

- Here are some common sense musings.

- The assassination of the second-most powerful man in Iran will echo through history, but what does it mean for markets?

- The answer is complicated, but your reaction function need not be.

- Here are some common sense musings.

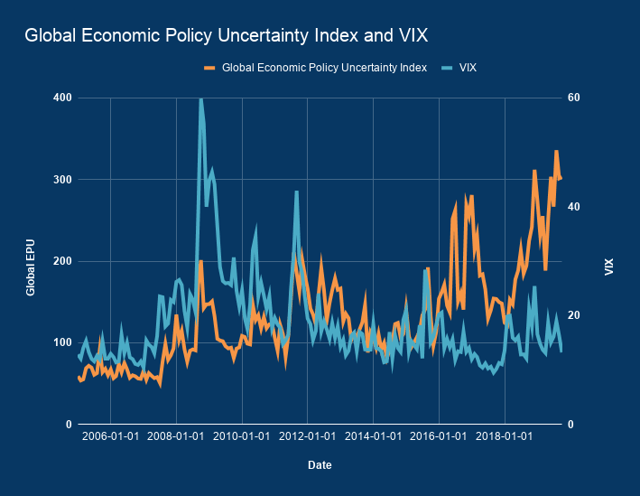

One of the defining features of markets over the past half-decade has been the disparity between, on one hand, news-based measures of policy and political uncertainty, and on the other, market-based measures of volatility.

This is a topic I've spent considerable time debating, discussing and otherwise expounding on for audiences here, there and everywhere (to speak colloquially).

Perhaps the simplest way to visualize this is to plot the VIX against the Global Economic Policy Uncertainty Index.

You can also use variations on the gauge available here. Additionally (and this is particularly germane in the current macro environment), there's a news-based trade policy uncertainty index available here.

I'm going to quote myself briefly and then transition to Friday's big news on the macro front.

Here's a bit of additional color on the above to set the stage (this is from a Tuesday article):

If you spend some time with the data, you can construct different versions of the visual, replacing the Global EPU with, for example, country-specific gauges. You can also replace the VIX with 3M10Y (for rates vol.) or indexes of FX vol. from JPMorgan or Deutsche Bank.

In almost all cases, you’ll come away with something that looks vaguely like the chart above – that is, a discernible rise in policy uncertainty disconnected from market-based measures of volatility in recent years. That disconnect was most glaring in 2017 during the low vol. bubble, and multiple attempts were made to explain it.

Generally speaking, the explanation is that central banks have succeeded in suppressing cross-asset volatility by perfecting the art of forward guidance, which anchors expectations, thereby enhancing the effect of rate cuts and asset purchases.

It was forward guidance which helped “buy the dip” morph from a derisive meme about retail investors into a viable (indeed, an almost infallible) trading “strategy”.

In the piece from which those excerpts are pulled, I suggested that 2020 is going to serve as yet another test of that dynamic.

Central banks pivoted dramatically in 2019, and while the bar for tightening is generally seen as impossibly high in 2020, it's almost by definition true that the bar for additional accommodation is lower this year than last if for no other reason than the close proximity of the lower bound and the bloated nature of balance sheets. Simply put, policymakers' "ammo" was already running low, and they expended some of it last year.

Central banks pivoted dramatically in 2019, and while the bar for tightening is generally seen as impossibly high in 2020, it's almost by definition true that the bar for additional accommodation is lower this year than last if for no other reason than the close proximity of the lower bound and the bloated nature of balance sheets. Simply put, policymakers' "ammo" was already running low, and they expended some of it last year.

Figurative "bullets" are thus even scarcer now and will likely be deployed only in a true emergency.

That latter consideration (that central banks would like, as much as possible, to remain on the sidelines in the hope that the easing delivered in 2019 is sufficient to prolong the cycle) will clash in 2020 with political drama associated with the US election, with intermittent trade flare-ups and with wrangling around final Brexit steps as the UK works to craft a post-divorce trade agreement with the EU. Those are the "known unknowns," so to speak.

In addition to those political challenges to central banks' express desire to avoid being forced into taking further accommodative measures to support the global economy and markets, 2020 will invariably bring a hodgepodge of black swans - every year does.

The question is how momentous they are, and, relatedly, whether they are consequential enough to override 2019's rate cuts and the resumption of G3 central bank balance sheet growth, in the minds of market participants.

Well, on Thursday evening, a geopolitical black swan the size of an elephant splashed into the waters of history when the US assassinated Qassem Soleimani, commander of Iran's Quds Force and, by almost any account you care to consult, one of the most influential figures in the Mideast. Oil obviously surged on the news.

Equities immediately plunged, Treasury yields fell and gold surged, in what Nomura's Charlie McElligott described as a "standard safe-haven bid."

This isn't the forum for breathless geopolitical musings, but as anyone with even a rudimentary understanding of Mideast affairs will attest, Soleimani's assassination is a historic event that will echo for decades. There is no debating the significance of what happened on Thursday evening.

There is a reason why this story was plastered on the front page of every major media outlet and newspaper across every country on Earth Friday, and there's a reason why "Franz Ferdinand" was trending on Twitter. Dozens of US lawmakers weighed in and every major country released some manner of statement (many through their foreign ministries).

In the simplest possible terms: The only way this could have been more significant is if the Trump administration had targeted Ayatollah Ali Khamenei himself, and even then, it wouldn't have the operational significance as a strike on Soleimani.

Should the average investor care about this? It's complicated, but below are some simple observations.

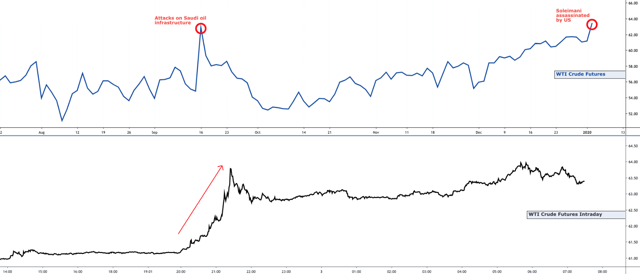

If you're in oil and gas names (or if you trade crude itself) this is arguably an even bigger deal than the attacks on Saudi Arabia's oil infrastructure in September (circled on the chart). Why?

Well, because Aramco turned out to be pretty proficient at repairing the damage and restoring lost supply, whereas, by virtue of being dead, Soleimani will not be so easily "restored."

As you've probably read by now wherever you get your news, Iran is going to respond, likely in dramatic fashion, and that raises the risk of further attacks on Saudi Arabia and more disruptions in the Strait of Hormuz and/or the Bab-el-Mandeb.

"Gold, silver and platinum [are] higher on the back of heightened geopolitical tensions since the news that a top Iranian general was killed in a US airstrike in Baghdad," SocGen's Kit Juckes wrote Friday morning, adding that "given the scope for tension to persist, a protracted period of higher oil prices has to be a risk."

"The focus of markets short-term is rationally the risk of a military response from Iran in a market that has become inherently bullish," Citi said, in a note suggesting Brent can move above $70 on Soleimani's death. "Possible retaliation may include targeted attacks on oil facilities in the region, attacks on pipelines or oil flows through the Strait of Hormuz," the bank went on to note.

I don't think I need to keep throwing analyst quotes at you when it comes to why this is relevant for energy names and oil market watchers. If you fancy yourself some stripe of oil aficionado and you couldn't, until today, rattle off some basic facts about Soleimani, you were never an oil aficionado. (Sorry.)

But what about for the broader market or, more simply, how about everyone else? Does the ubiquitous "long-term investor" need to care?

The short answer is always "no." If you're the "I'm going to buy an S&P 500 index fund when I'm 18 and sit on it until I'm 65 come hell or high water" type, then nothing ever matters, not even a 2008-style global crash, let alone the death of one man. (And thank God for that, because think how silly you'd feel right now if you'd sold it all at the lows in 2008!)

But, this time the "no" comes with a big caveat. Thursday night's drone strike has the very real potential to change the course of history in the Mideast. Indeed, is already has. This isn't just "a general," so to speak. This is, to paraphrase one expert who spoke to The New York Times, the equivalent of someone assassinating the CIA Director, the JSOC Commander and the Secretary of State all at once.

So, what to do?

How does an average investor even begin to contemplate something like this and incorporate it into a "strategy?"

First thing's first: The risk of a near term systematic, cascading de-leveraging event like those witnessed during some of the more acute selloffs we've seen in recent years is low. Dealers are still long gamma, and CTAs are still deeply "in trend' in Spooz.

In plain English, that just means that spot SPX would have to move sharply lower (and in a hurry) to kick off the kind of selling-begets-more-selling loop that took hold during, for example, mid-August and early May 2019, and also in early October 2018.

In other words, this isn't necessarily a situation like that which existed in early May of 2019, when all it took was one irritated trade tweet on a Sunday evening to push S&P futures through key levels that started tipping dominoes. So, no need to panic in the near term.

In the medium term, use some common sense, right? Given the above, you now know enough about this to have some conception of the potential for foreign policy blowback.

Although Soleimani's death will never really "blow over," the threat of direct retaliation will obviously be the most acute over the next six or so months.

Think about that, and then consider the following two-pane, which illustrates the extent to which we were, until Friday anyway, in the midst of a "melt-up."

The S&P was overbought, the VIX was below its average in 2018/2019 and stocks had risen in 12 of 13 weeks (they will likely snap that streak on Friday).

It's stretched. Period. And now you've got a historic geopolitical black swan in play.

Does that mean I'm going to try to impress everyone here with some kind of complex hedging strategy? No. I'll do that later (just kidding).

Rather, I would simply say that while surging crude could conceivably push up breakevens, that likely won't be enough to offset the safe-haven bid for US Treasurys if tensions continue to rise.

With US 10-year yields having jumped ~40bps off the lows in August, it might not be a terrible time to add some bonds for protection. Sure, there's less scope for bonds to act as a hedge given that, historically speaking, yields are at rock-bottom levels, but you could have said the same thing at the end of 2018, and bonds worked out ok last year, didn't they?

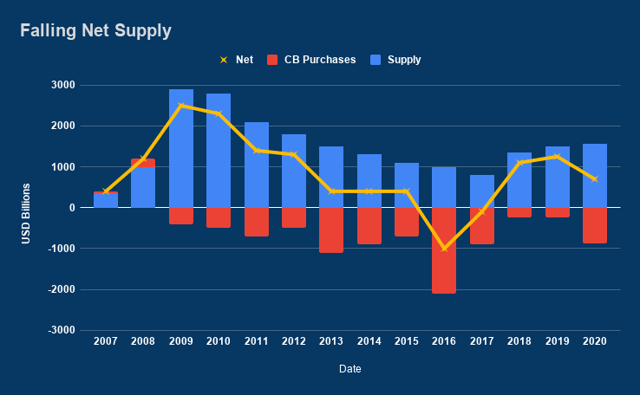

On a related note, consider that the net supply (i.e., government issuance minus central bank buying) of safe-haven bonds is set to fall this year for the first time since 2016 thanks in large part to the restart of net asset purchases by the ECB and the Fed's reserve management efforts.

That means safe-havens are getting scarce again, which could help bonds perform in 2020 even if geopolitical tensions abate, growth holds up and central banks refrain from cutting rates further.

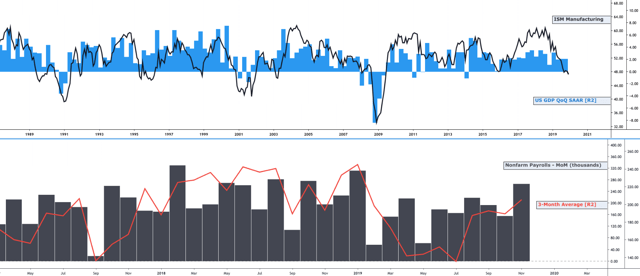

As an aside, ISM manufacturing printed a new post-2009 low on Friday, defying expectations for a rebound and widening the gap with IHS Markit's factory gauge.

Although almost all other indicators are pointing to a positive inflection in the US economy, ISM remains stubborn and is consistent with growth of around 1.3%.

That visual (i.e., the juxtaposition between ISM, GDP and the robust labor market) remains a "who's got it wrong?" situation. If ISM is "right," then bonds will likely be just fine going forward.

Over the medium- to longer-term, the situation between Washington and Tehran seems binary.

Either Soleimani's death will galvanize public support for the regime at a time when it was slipping following the deadly fuel protests, hardening the resolve of the theocracy and making the situation immeasurably more precarious for the West, or the opposite will occur, where that means the Commander's demise will mark a turning point beyond which the populace sees an opportunity to rise up in the absence of a figure whose mystique was a key element in preserving an increasingly shaky status quo.

I would venture that the former is far more likely than the latter. If the regime's resolve only hardens and the Iranian public rallies to the cause, it could well lead to a year's worth of threats and tit-for-tat retaliations that end up influencing the US election.

This week, Bernie Sanders said his campaign out-raised every Democrat in the field by a country mile in the fourth quarter. Sanders is a non-interventionist.

Of course, so is President Trump, ostensibly.

If Sanders were to get the nomination and the Iran problem were to fester into the election, he would doubtlessly use it against the President.

My own well-known political leanings notwithstanding, any objective (i.e., honest) assessment of a potential Sanders win has US stocks careening sharply lower.

Remember, the tax cuts accounted for a massive boost to earnings. Any threat of repeal would lead to an immediate repricing of equities.

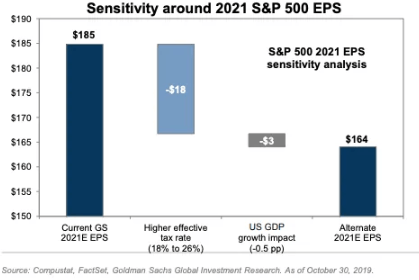

Here, for instance, is what happens to Goldman’s 2021 S&P EPS outlook assuming a higher effective tax rate:

(Goldman)

(Goldman)

Slap a 17X multiple on that $164 and see what comes out. (You won't like it.)

Now let's bring this full circle to where we started. Central banks spent all of last year righting both their own "wrongs" (where that primarily means the Fed making up for over-tightening) and taking out insurance against the possibility that erratic politics and an aversion to fiscal stimulus in some locales (e.g., Germany) will end up undercutting the stability monetary policy has worked so hard to foster over the past decade.

With rates at or near the lower bound and balance sheets still bloated, there is now less figurative ammo than ever to deploy in the event the deployment of literal ammo ends up destabilizing markets or undercutting the global economy at a delicate juncture.

It's been a decade since market-based measures of volatility were allowed to catch up to the surge in what BofA has called "politicians' implied vol.," as proxied above by the EPU. One of the key risks I've identified for 2020 is that the gap illustrated in the very first visual above closes.

On that score, 2020 started with a bang - figuratively and literally.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario