By: Allison Fedirka

It appears as though Japan, of all countries, is trying to help Iran out of its predicament with the United States. In May, for example, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif traveled to Tokyo, where he met with Japan’s foreign minister and prime minister.

The visit came a few days after Iran issued a 60-day warning that it would resume uranium enrichment if a new nuclear deal was not reached. One week after the visit, rumors started to emerge that Japan could help play a role in U.S.-Iran relations.

These rumors were fueled by a meeting on May 24 between Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and then-U.S. National Security Adviser John Bolton, and then by President Donald Trump’s official state visit to Tokyo the next day.

Then, in early June, Abe said he would pay an official visit to Iran on June 12-14, the first of its kind since the Iranian Revolution of 1979. (During the visit, he was the first Japanese prime minister to meet with Iran’s supreme leader.)

All the while, tensions between the U.S. and Iran were escalating, culminating in increased attacks and military operations in the Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz, including an attack on a Japanese-owned vessel.

Japan helped eased tensions again in August after Zarif’s unannounced appearance on the sidelines of the G-7 summit in France.

After the summit, Zarif went to Tokyo to discuss his opposition to U.S. efforts for building a coalition of naval forces, friendly to the U.S., to safeguard sea-lanes in the Persian Gulf.

Most recently, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani paid a visit to Japan on Dec. 20, a first in 18 years. The meeting, like the ones before it, was shrouded in privacy, but Japanese media have since reported on Japan-Iran developments, highlighting Japan’s role as an intermediary between the two global rivals.

Media outlets in Japan have even quoted Abe as saying the purpose of the meetings was to avoid war through dialogue.

Security and Economic Needs

Japan has put its money where its mouth is.

During Abe’s June visit to Tehran, he expressed an interest in investing in Chabahar, the India-backed port and Tehran’s only port on the coast.

Its current capacity is 8.5 million tons of cargo per year, though port authorities say it currently operates at 10 percent capacity largely due to sanctions.

The port is seen as a counter to Chinese expansion in the region through the Belt and Road Initiative, a constant concern of Japan’s.

It’s a mutually beneficial arrangement. Iran gets much-needed investment, and Japan (possibly) gets a foothold in a strategic port along the Gulf of Oman that could serve as a counterweight to potential Chinese naval bases nearby while improving its budding military relationship with India. More generally Japan has called for support for the Iran nuclear agreement but refrained from saying anything substantial on U.S. sanctions against Iran.

.

It has also declined to join the U.S. coalition to patrol and protect merchant ships in the Middle East, opting instead to independently send its navy on information-gathering missions around the Strait of Hormuz and Bab el-Mandeb shipping lanes. Japan said it will still cooperate with the U.S. Navy despite not formally joining the coalition. (Its absence sits well with Iran, which has a growing list of enemies in the region.)

Tokyo later upgraded its deployment plans to include sending warships to the Middle East to protect vital shipments of oil and natural gas and made it clear that Japanese warships would not patrol the contentious Strait of Hormuz, the critical chokepoint where an outbreak of conflict with Iran would be most likely. The move complements U.S.-led efforts while still giving Japanese forces the opportunity to protect energy shipments.

The forces prompting Iran and Japan to work closer together stem from security and economic needs. The Iranian economy has been crippled by sanctions, inflation is soaring, the currency has lost 70 percent of its value in one year, and there are regular shortages of basic goods. U.S. sanctions have severely limited Tehran’s options for righting the ship. One option is to improve its public appearance to reassure its citizens that the situation is under control.

Another strategy has been to court other countries for support. Russia and China have stepped in to help circumvent U.S. sanctions, but because the U.S. also considers them its enemies, they are in no position to help ease tensions or resolve core issues. Economic sanctions hamper diplomatic outreach too.

The fact that Iran’s prospective business partners risk U.S. retaliation has been a major factor in slowing Europe’s progress toward implementing plans for the INSTEX trading system. Other potential allies such as India can’t help either, But Japan can.

It has a strategic relationship with the U.S., giving it some room to call the shots with Washington and at the same time with vested interests in helping Iran.

Japan’s economic and security strategy dictates that it should improve ties with Iran and the U.S. to secure safe maritime transit from the Gulf to the Indian Ocean. Japan depends on imports for its energy supply.

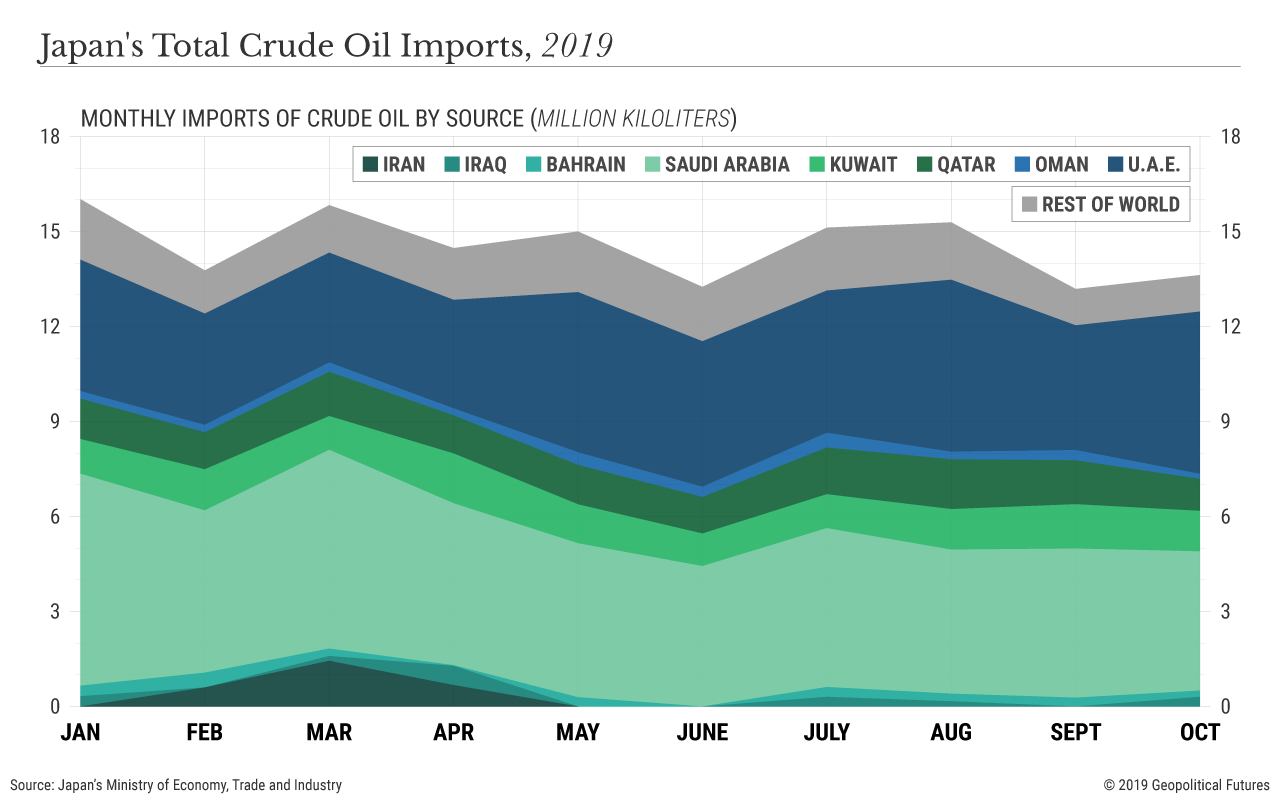

Nearl 90 percent of Japan’s oil comes from the Middle East. Naturally, it requires a steady supply of affordable oil from the region and therefore does not want a conflict to break out in the Persian Gulf or Red Sea that would jeopardize supply and raise the cost of crude, both of which would hurt Japan’s economy.

Japan also has an interest in containing and remaining on even footing with its rival, China, which has been working to expand its reach westward into the Middle East and across the Indian Ocean into the Gulf.

Japan does not want to see China (or Russia, for that matter) dominating the Iranian oil market – to say nothing of Japan’s desire to expand its blue-water naval capabilities and training experience, which aligns with Washington’s interest in regional allies taking over more of their security responsibilities.

The U.S. Remains Quiet

The United States has been unequivocal in its decision to leave the Iran nuclear deal, adamant that countries not do business with Iran, and unfailing in its criticism of those that support Iran. And yet, Washington has been uncharacteristically quiet about Japan’s budding relationship with Iran.

.

After all, Japan and the U.S. are security allies that work closely to contain China, so Tokyo must walk a fine line. It has, for example, remained on Washington’s good side by creatively tip-toeing around U.S. sanctions in Chabahar, which is used to move food and thus exempt from U.S. reprisal.

Japan has also done its part to coordinate actions closely with the U.S. Prior to Abe’s visit to Tehran and after Rouhani’s visit to Japan, Trump and Abe held extensive and private phone conversations.

Though the U.S. approves of Japan’s early efforts to help break the impasse with Iran, there are reasons for remaining quiet over the matter. First, these are the early stages, and it is unclear if the strategy will work out. There is also the fact that the U.S. cannot decrease its pressure on Iran prematurely or come across as backing down with Iran and meeting Tehran’s demands for dialogue.

The U.S. would welcome reconciliation with Iran. Publicly, Washington has conditions that Iran cannot accept despite Rouhani’s frequent comments about being open for dialogue.

Tehran is not willing to end all nuclear activity to open the way for talks and therefore stresses the need for “the right conditions” to move forward. However, the U.S. has subtly shown its flexibility on the matter.

For example, just before the news that Japan was ready to invest in Chabahar, U.S. officials again said exemptions for port activity (for India) remain in place so long as the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps is not involved.

.

It’s worth noting that for all of Washington’s public support for regime change in Iran, it’s not clear that that’s what Washington really wants since it can’t control what will replace it.

Just look at the problems that arose in Syria and the emergence of the Islamic State. .

There is no guarantee that a government more aligned with Washington’s worldview would take over – in fact, it’s rather unlikely. Iran has a highly factitious political system that cannot be easily reduced to pro- or anti-American.

It’s too early to tell how successful Japan’s mediation efforts will be. But it’s clear that the U.S. and Iran are on board with these efforts, because they suggest a broad, comprehensive understanding may be possible – one that goes beyond Iran. In addition to Iran, Japan has discussed Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Palestine with his Iranian and American counterparts.

.

It’s also clear that there are still some major gaps in understanding that need to be overcome before significant progress in talks can be made. Japanese press reported that Iran feels the U.S. miscalculated the Iranian viewpoint and Rouhani reiterated his readiness to hold talks with the U.S. if it revises its approach.

.

These are vague instructions on what needs to change from the Iranian point of view but nevertheless provide guidance for Washington on how to think about ways to break the impasse with Iran, with Japan’s help.

| |

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario