By: GPF Staff

Introduction

A year is an arbitrary moment. It is short, its length determined by a planet’s rotation around a sun. It is merely a moment in a longer and more complex tale in which figures who tower for a time pass by unnoticed, when the triumphs and tragedies that rivet us all fade away, all but forgotten. In that sense, forecasting what happens next year is possible only if it is viewed as one frame of a much longer movie.

Our annual forecast must therefore be framed as such. For us, the story begins in 1991. Many things happened in and around that year: The Chinese economic miracle began its historic surge; the Japanese economic miracle failed; the Maastricht treaty was signed; Operation Desert Storm was launched; the Soviet Union collapsed.

Since 1492, when the first global system emerged, there was always a European power at its head. That changed in 1991. For the first time in 500 years, there was no European global power.

The only global power was the United States, native to both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, the largest economy by far and the only global military power, dominated the international system.

At the same time, the center of gravity in Asia shifted from Japan to China. Europe attempted the creation of wide-ranging federation. The U.S. presence in Saudi Arabia fueled the rise of al-Qaida. The rest of the globe found itself caught up in these whirlwinds.

Thus emerged a new epoch. The world has been trying to adjust to the new normal set forth around 1991. The U.S. is still struggling with its new power, the Russians are trying to resurrect their past, the Chinese hope to avoid Japan’s fate, Europe is struggling to define what the European Union really means. And the defeat of the jihadists has led to the rise of Iran.

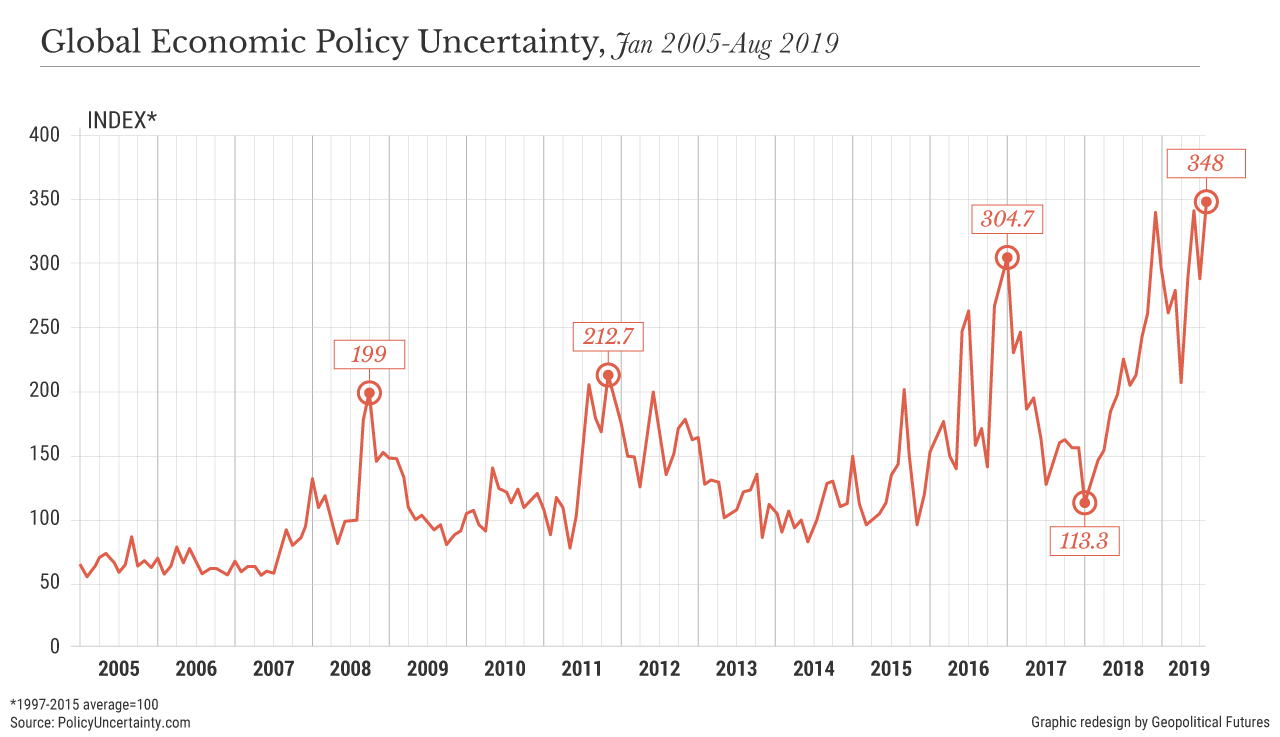

Which brings us to 2020. Some years are dominated by war, some by politics and some by economics. All three are always present, but in most years one dominates. 2020 will be dominated by economic competition, the further decay of the global free trade system, and the decline of the illusion of amiable interdependence.

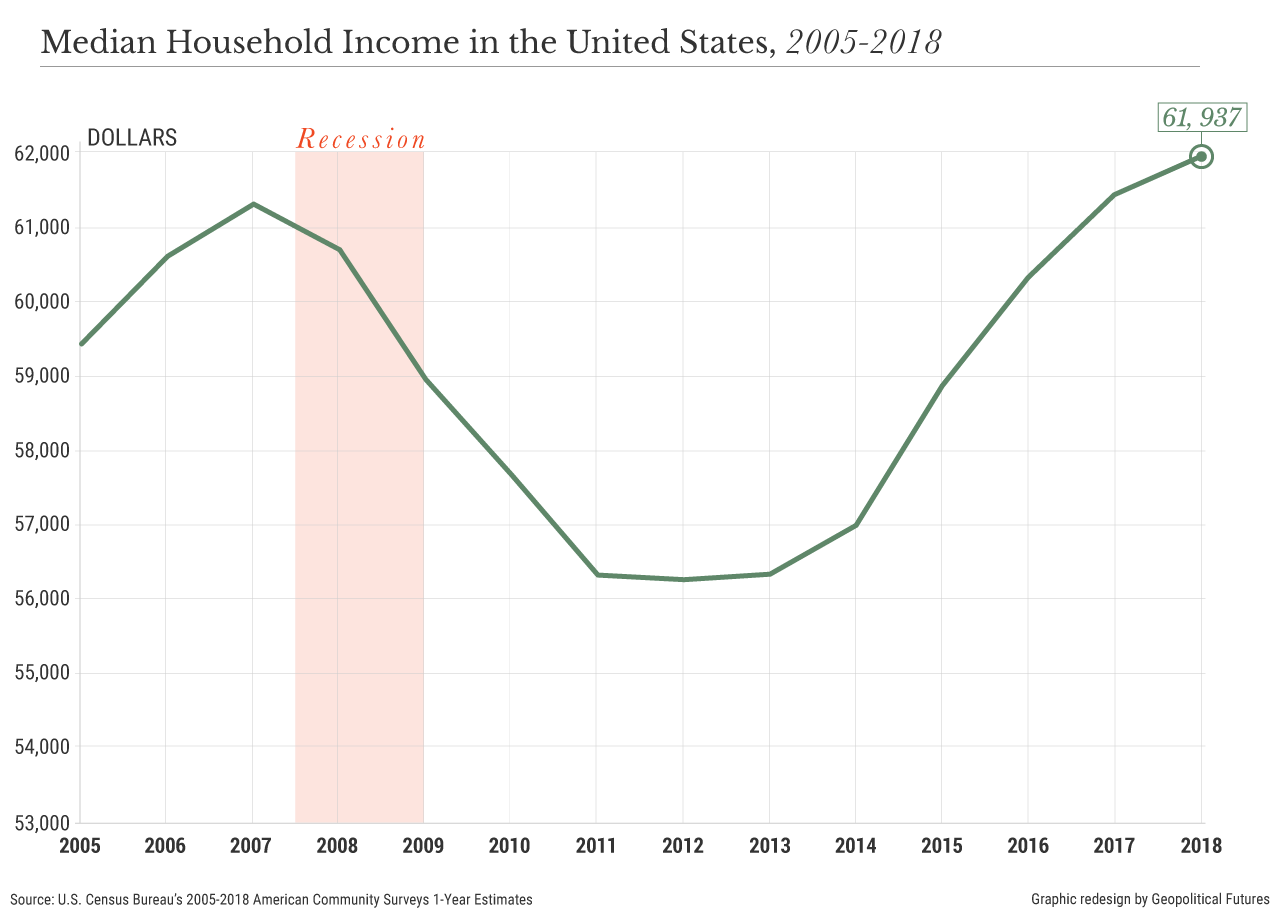

As we anticipated in our 2019 forecast, a global economic slowdown is underway. This is a cyclical downturn that would normally not create major social, political and international forces. But because the 2008 economic crisis generated structural problems the international system has still yet to metabolize, the impact of this slowdown will generate substantially more non-economic consequences than would normally be expected.

Slowed economic growth limited the growth in appetites for imports, which struck hard at exporters of manufactured goods (China) and industrial minerals (Russia). And though they have stabilized the situation somewhat, they have yet to reverse it, so the pressure caused by the downturns is still aggravating social tensions.

This crisis manifests itself in a range of seemingly unrelated political confrontations, such as between the United States and China, Britain and the European Union, the U.S. and Iran, to say nothing of the internal instability in South America and the United States. Britain was confronted by an EU that was indifferent to the class that lost much after 2008. China confronted a world that consumed less, and competitors that produced more, placing China in a crisis where U.S. demands could not be accommodated.

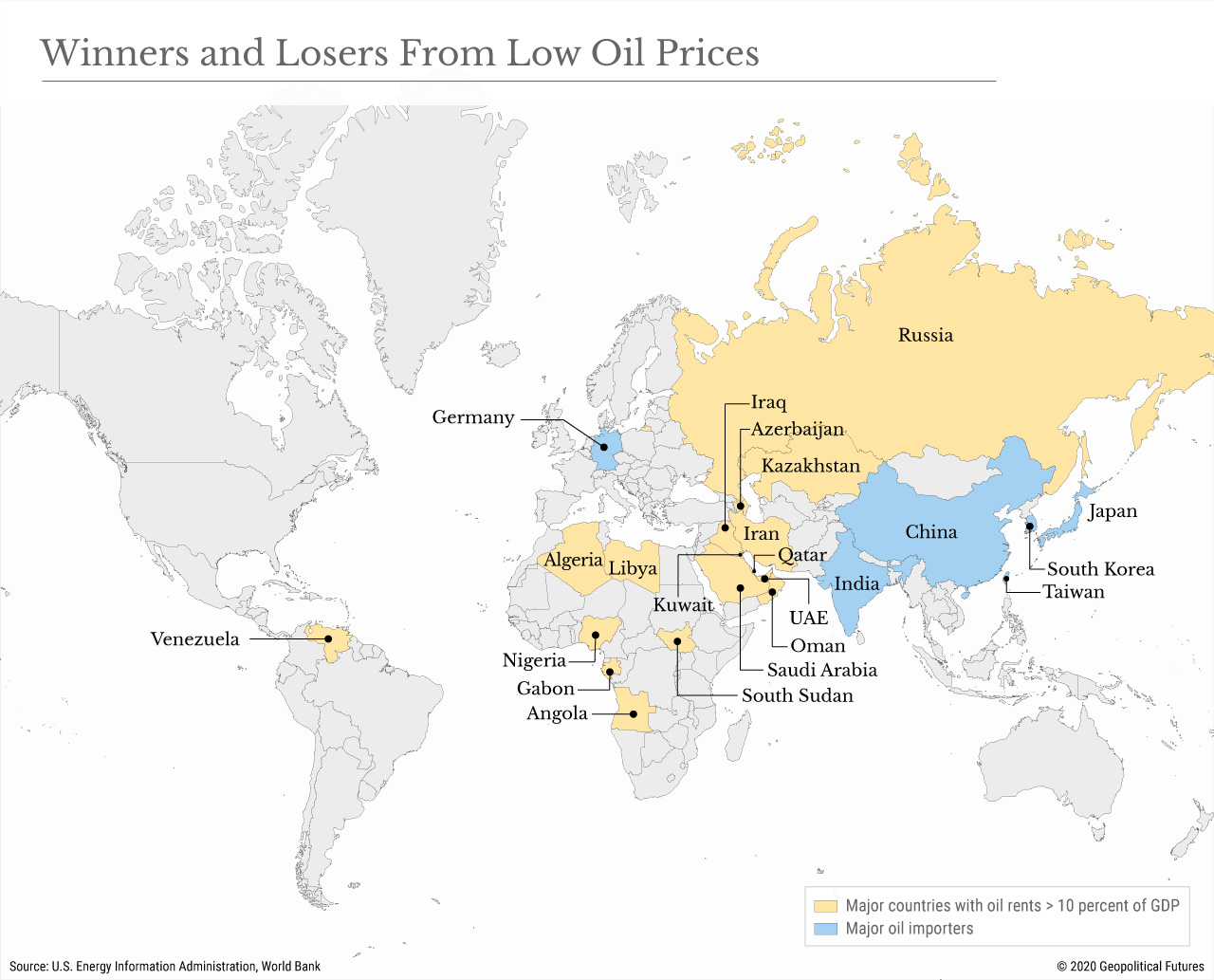

The weakness of oil prices made Iran uniquely vulnerable to U.S. economic pressures, and Iran struck back by other means. All of these seem unconnected, but the connection is the massive economic shift that began in 2008, paused without being solved, and is now accelerating once again. These trends began before 2020 and will end long after 2020, but they will be the hallmark of the coming year.

As I explained in "The Next 100 Years," people tend to think the next moment will be the same as the prior one. At the height of the British Empire, it was inconceivable that British power was impermanent. But nations, like empires themselves, rise and fall. Our 2020 forecast is made in the context of this model.

George

Friedman, chairman

Forecasts

Global

1. Economic dysfunction will be the main driver of the international system in 2020. Economic stress does not simply flow from whether the economy grows or declines by a percent; it arises from shifts in the pattern of economic behavior. This in turn affects social realities and leads to political instability. Growth may continue, but a dramatic slowdown in growth can have significant consequences. We forecast a slowing global economy.

2. The most important dimension of the slowdown will be the increase in social instability, which was triggered by the 2008 financial crisis and ameliorated in recent years but will now accelerate. Internal tensions in many countries are already underway and will become more intense and less manageable in 2020.

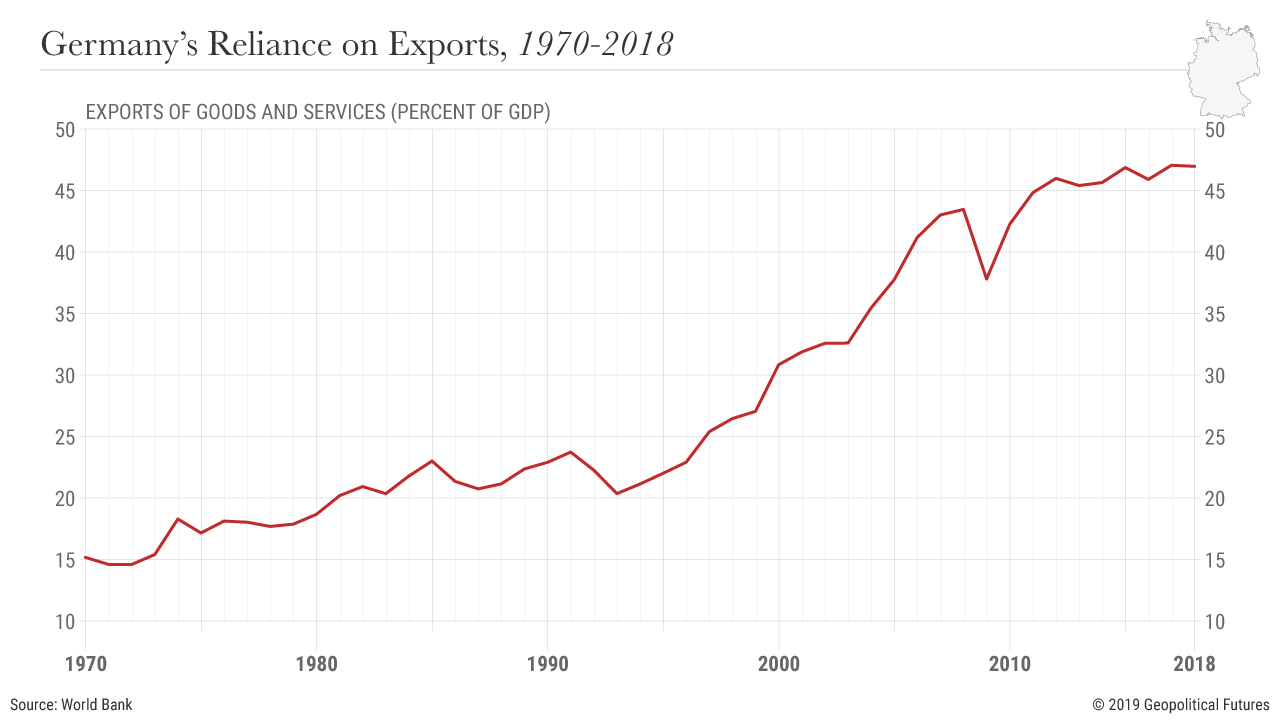

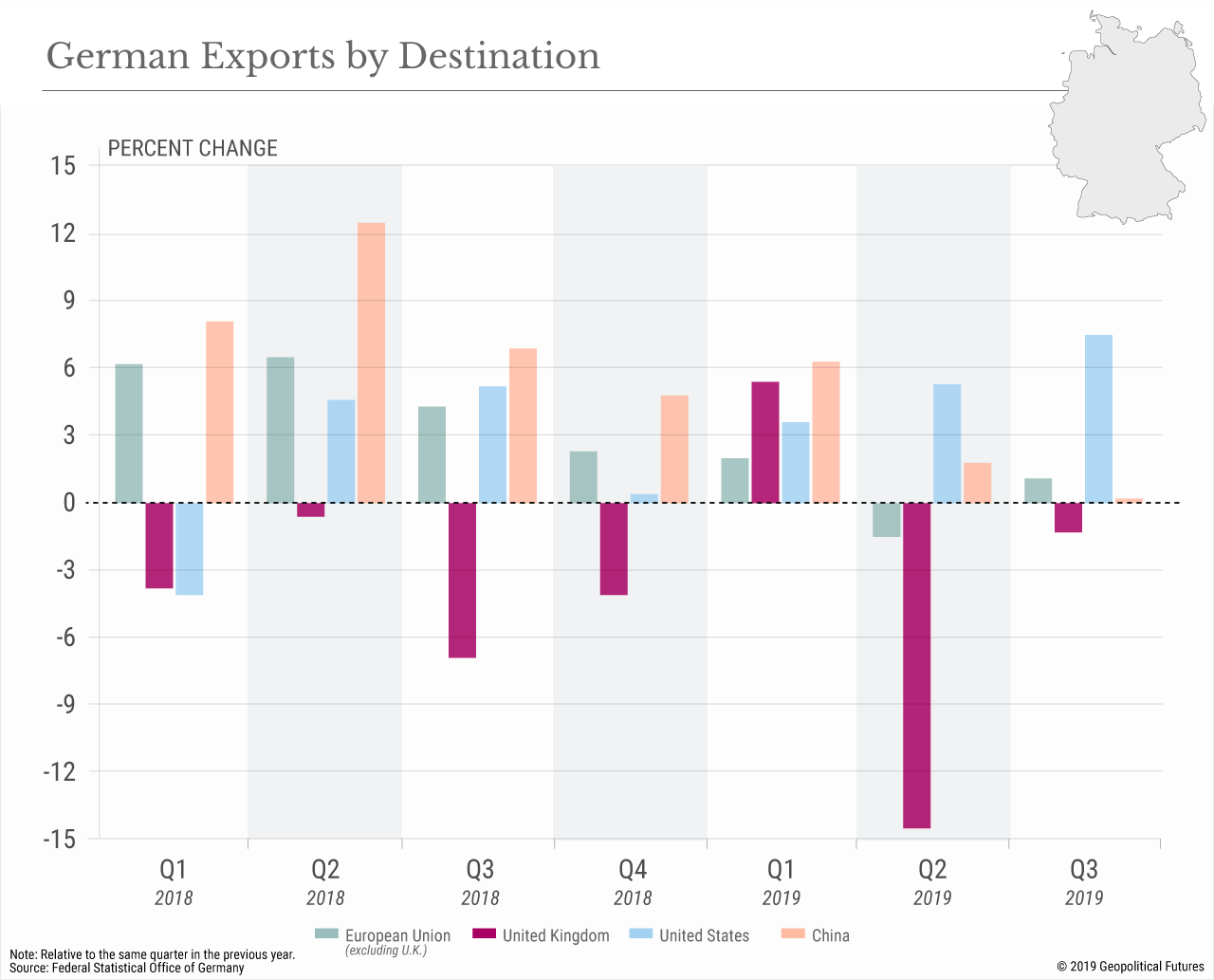

3. Nations most vulnerable to the slowdown will be exporting nations. The countries that will be most destabilizing to the global system will be major economies that are dependent on exports. Germany and China are the most vulnerable and will have the greatest impact globally.

4. Trade issues will play a dominant role in generating international tensions.

Net importers will try to use the crisis not only to redefine their economic relations but also to shift political relations. Disputes, conflicts and even wars will pivot around importers’ use of their economic power and the weakness of exporters.

5. Downward pressure on production will reduce the price of primary commodities, increasing internal instability in countries depending on oil and other exports.

North America

1. The economic downturn will intensify the social crisis in the United States, compounding the ongoing political crisis.

2. The U.S. will be inward focused due to political forces, and its foreign policy will be driven by two principles: exploiting the problems of exporters, particularly China and Germany, and avoiding military actions.

3. U.S. strategy will continue to shift from military action to economic action in which the U.S. uses its power as a massive importer to shape the behavior of adversarial nations.

4. The United States’ major focus abroad will be on breaking the Iranian sphere of influence and defining its approach to rising Turkish power. The United States’ relationship with Asia for the moment will fall into a tense but primarily static mode.

5. The U.S. and global economic slowdowns will provoke a political crisis in Mexico.

Europe

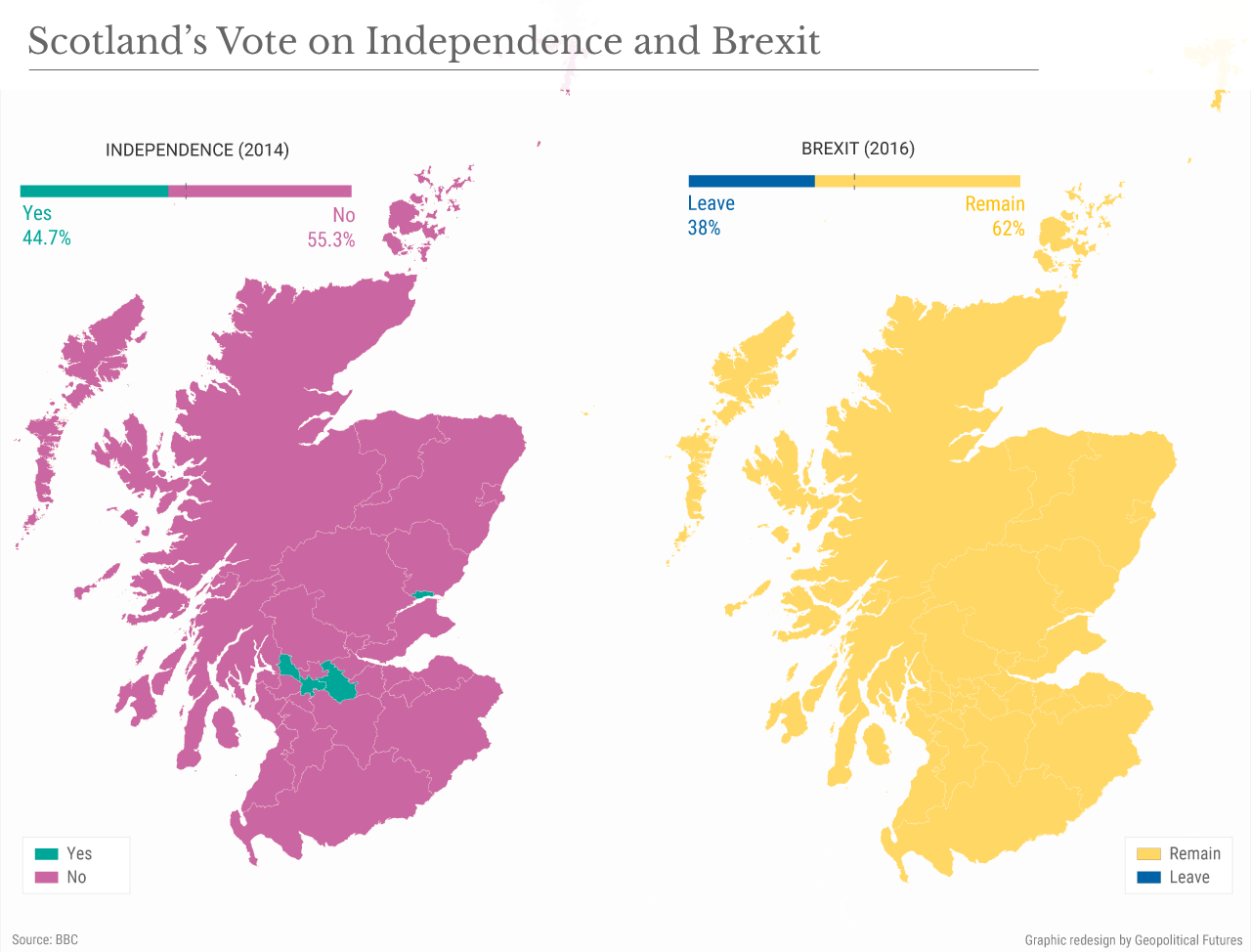

1. The most important European issue in 2020 will be the degree of instability in the United Kingdom. Regardless of how Brexit resolves itself, the unity of the United Kingdom has been shaken to the core.

Aside from social tensions, the relationship between England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and even Wales will be on the table this year. This level of instability in a pillar of Europe will resonate. As the United Kingdom destabilizes, the destabilization will accelerate a centrifugal process on the Continent.

The United Kingdom will not fragment in 2020, but there will be a significant crisis of confidence within the EU concerning both Germany’s leadership and the management model that has emerged in Brussels.

2. The crisis in exports will strike the European Union in two ways.

First, Germany, which earns almost 50 percent of its gross domestic product from exports and counts the United States as its largest single customer, will see its export value contract, which will affect its GDP on a 2-to-1 basis.

This will intensify political instability. Second, other EU economies are deeply intertwined with the German value chain and German exports.

The EU is increasingly under political attack in these countries, and this will cause both an economic problem and, more important to the EU, a major political challenge for maintaining the EU.

3. The United Kingdom will move toward a trade agreement with the United States shortly after Brexit that will become entangled in the U.S. election but will ultimately be agreed on.

Russia

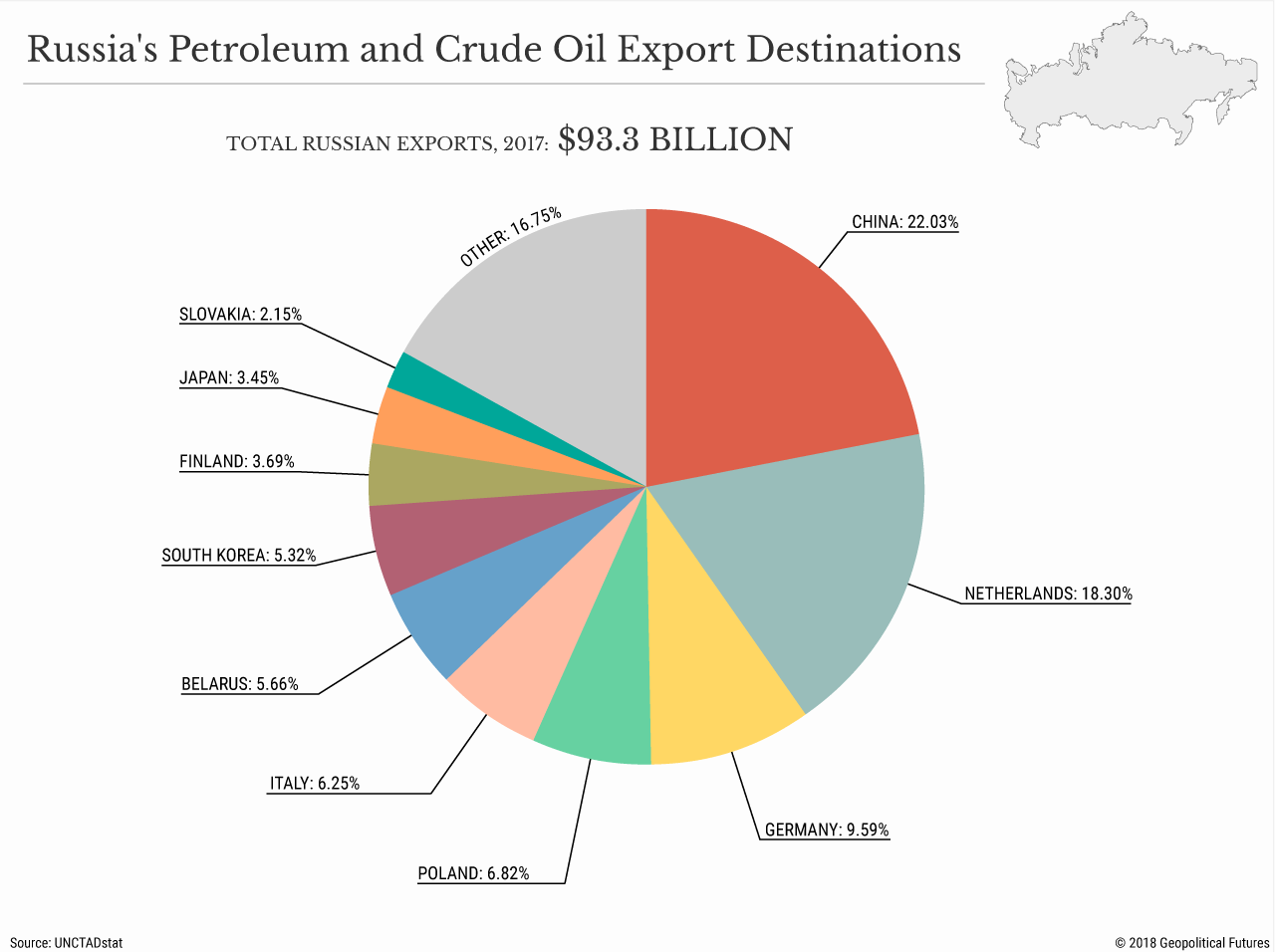

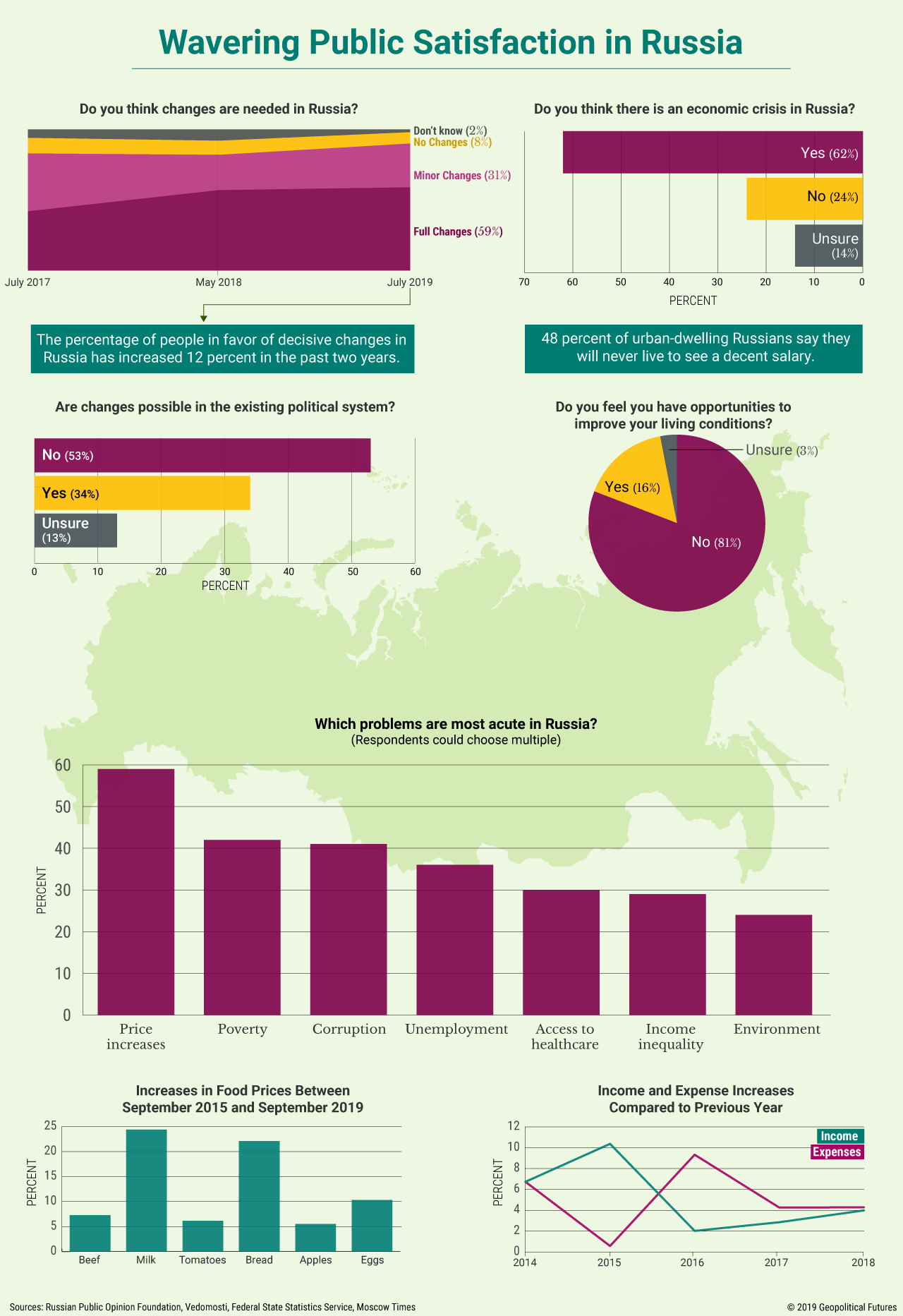

1. Russia has managed to maintain stability despite the massive downturn in oil prices.

However, there are significant constraints on the standard of living and government services outside the major cities.

The export crisis will strike Russia particularly sharply because its economy is largely driven by oil and gas exports.

This will increase dissatisfaction in Russia, but not to a point threatening the regime.

2. Russia’s foreign policy will continue to be on the surface aggressive but in practice very cautious.

Russia must assert its politico-military capabilities but not trigger a response from nations excessively frightened by them, particularly the United States.

It will thus employ a strategy of, say, using limited assets in non-critical areas to establish credibility without risk.

Russia will be active in areas like Venezuela and some Middle East countries.

It will be careful not to engage in areas of fundamental interest to the United States but will posture in other areas.

3. The United States is having a presidential election in 2020.

Meddling in the 2016 election resulted in the unification of both American political parties in an anti-Russian posture, along with increased U.S. sanctions.

The Russians will not attempt this again, as their strategy must be to divide U.S. opinion on Russia, not unite it.

Middle East

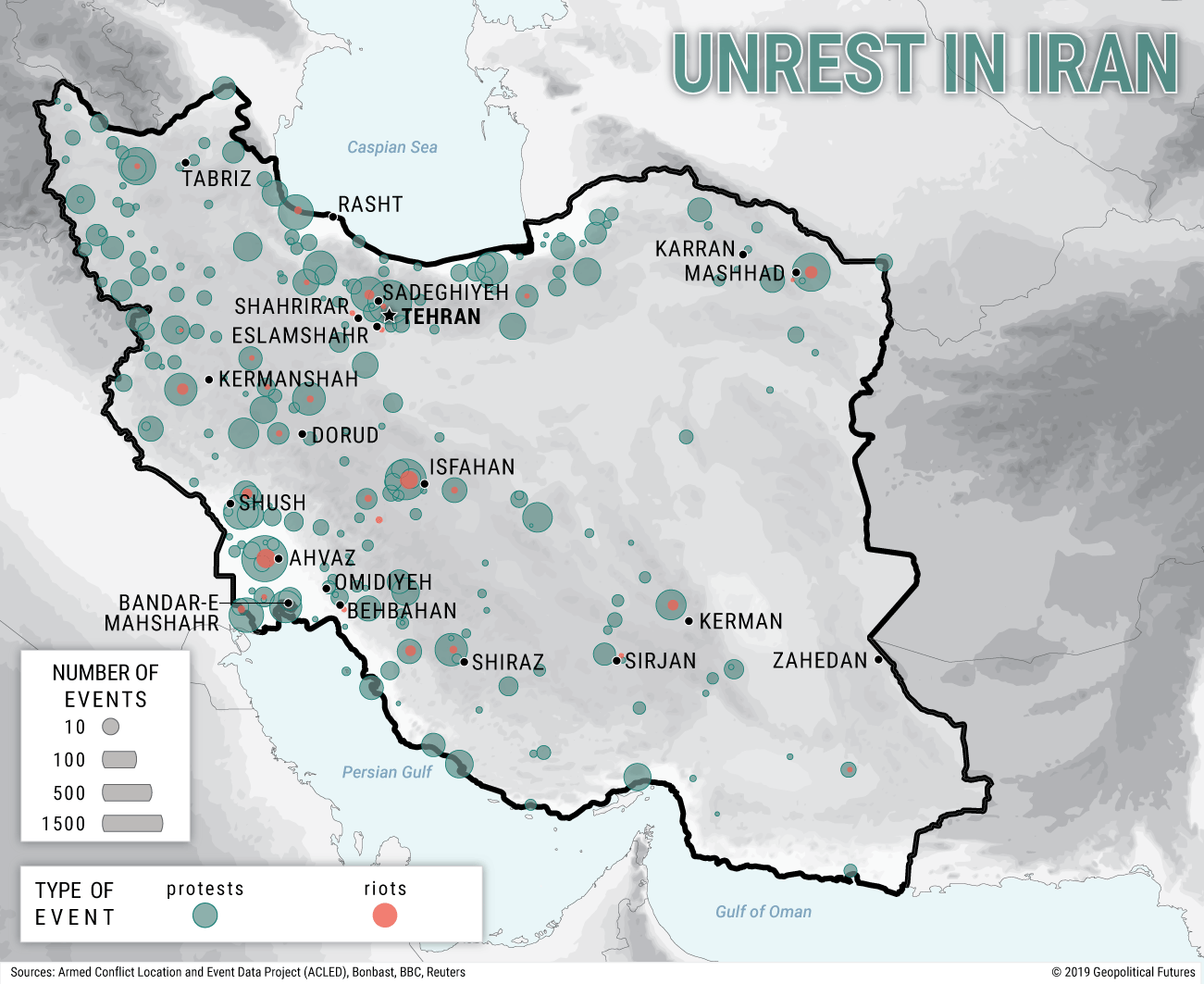

1. U.S. economic sanctions and the formation of an Israeli-Saudi-UAE coalition have challenged the Iranian move to the Mediterranean.

The United States wishes to avoid military confrontation, and therefore the most likely counter to Iran’s own counters will be covert operations by the anti-Iran coalition in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon.

These will be designed to destabilize the Iranian position while maintaining heightened pressure on Iran’s economy.

The pressure will create a political crisis in Iran as its expansion efforts and the domestic situation are weakened.

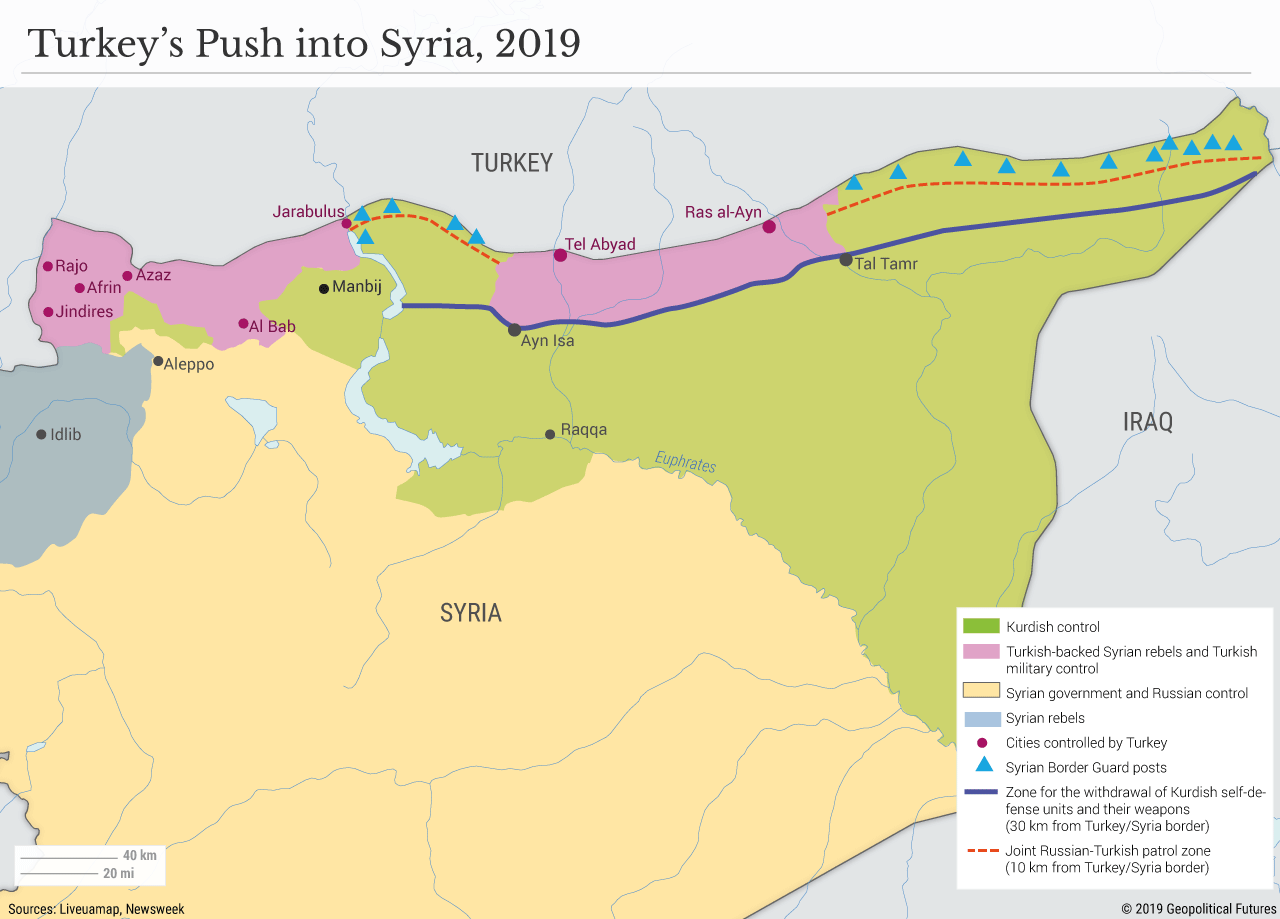

2. In the long term, Turkey is the dominant regional power.

Except for cross-border operations into northern Syria, it has thus far hesitated to undertake activities far beyond its border.

By the waning months of 2019, however, Turkish troops were again in northern Syria, drillships were venturing farther and farther out in the Eastern Mediterranean, and Ankara was offering to send troops to Libya and signing maritime delimitation deals with one of Libya’s rival governments.

The Turks will increase their assertiveness in 2020, with dramatic consequences for the region.

3. The vague alignment of Turkey and Russia will come to an end over Libya and Syria. On Libya, they find themselves on opposing sides. Russia is Syria’s ally, Turkey its enemy. Turkey does not trust Iran’s intentions to its south. Therefore, with fits and starts, Turkey will move closer to the United States.

Asia

1. China will struggle to maintain economic stability, which was imperiled even before the trade war with the U.S. Considering the state of the global economy, neither resolution of the trade war nor financial reforms will restore China’s economic power.

This will turn into an internal political struggle between competing interests.

The viability of China’s financial and banking system will be tested.

2. To compensate for the internal weakness, China will seek to stabilize the social system by increasing repression.

In addition, China will become more assertive militarily, particularly in the South China Sea but also the East China Sea as it tries to take advantage of the South Korea-Japan confrontation.

We expect quiet political tensions among the elite to grow.

3. The confrontation with China and North Korea will dramatically increase Japan’s drive to boost its military.

Although allied with the United States, Japan faces too many potential threats in the region not to build a more significant offensive capability.

South America

1. Russia will use political ties, supported by modest economic efforts, to regain more active influence in the Caribbean.

2. China will attempt to increase influence more generally in South America through limited economic cooperation complemented by increased political engagement.

3. The U.S.-Colombia relationship will be the priority relationship in the region for Washington.

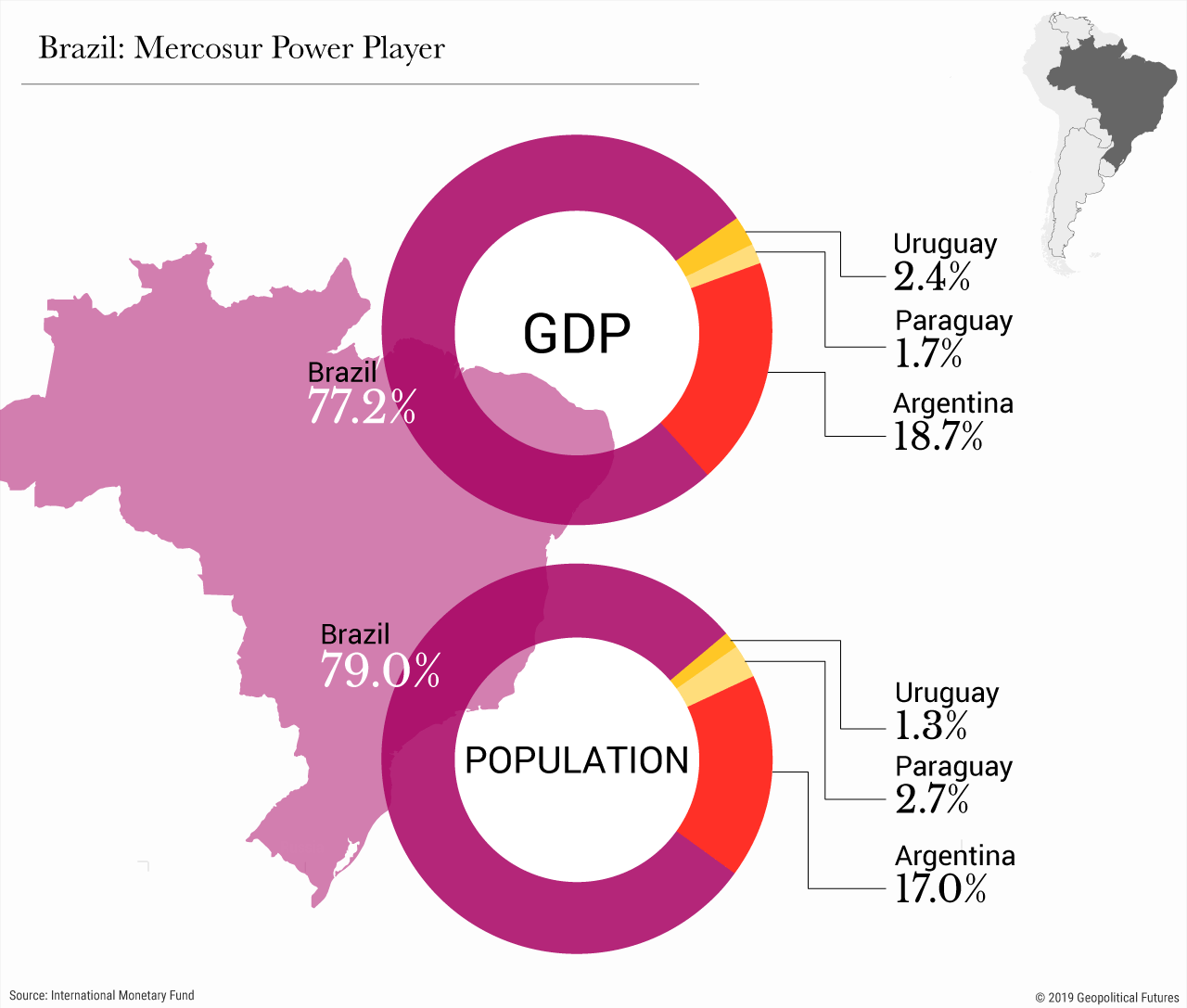

4. Brazil will use its weight and dominance in Mercosur to get Argentina to fall in line with Brasilia’s desired trade policies.

There will likely be much resistance, and Brazil will then shift to questioning the utility of Mercosur to get Argentina to fall in line.

Australia/New Zealand

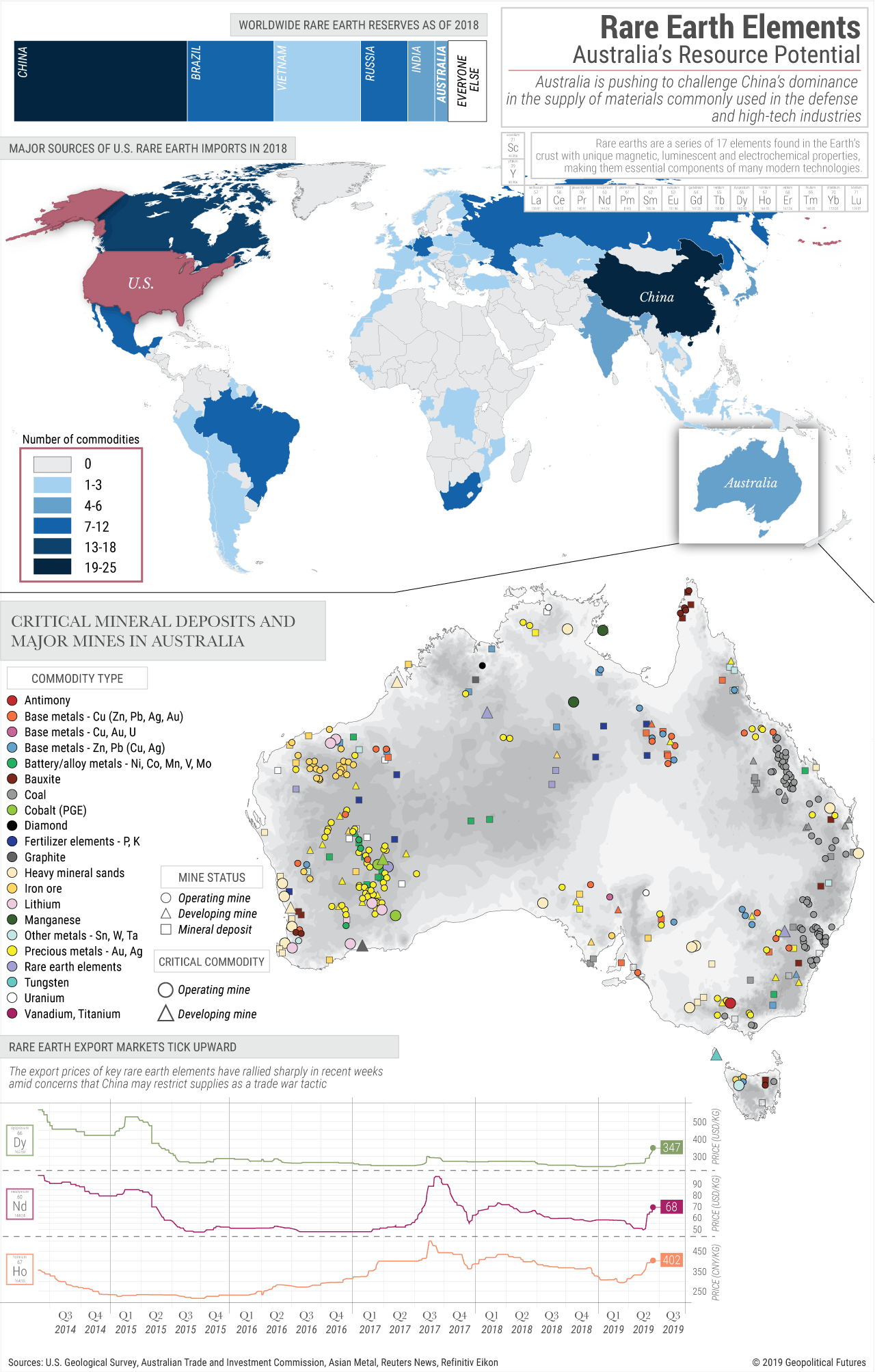

1. Australia will find itself in an increasingly unstable region, with the sea lanes on which it depends for trade increasingly at risk.

It will therefore have to maintain and enhance its relationship with the United States.

2. As China’s economy weakens, the need to align militarily with the United States will outweigh the desire to export to China.

3. The United Kingdom’s shift toward the U.S. will contribute to the creation of a trade bloc that will include Australia and other sources of industrial minerals.

The bloc will act as an alternative to the Chinese market, as China’s appetite for these minerals declines.

Conclusion

Our forecasts make sense only in the context of the broader post-1991 and post-2008 models.

They define the constraints and imperatives driving the components of the international system.

In most ways, the broader processes are more valuable guides to 2020 than the forecasts we outline here, simply because they tell us the general thrust of events and are less open to variation than the forecasts themselves.

Nevertheless, since the forecasts are embedded in the broader models, their general trajectory remains valid, even though variations in detail are likely.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario