North Korea Would Like Your Attention

By: Phillip Orchard

Last April, Kim Jong Un issued a largely-overlooked ultimatum to the U.S.: Break the impasse in the negotiations over the North’s nuclear program by the end of the year, or else.

Pyongyang, however, apparently didn’t feel the need to provide any detail on what happens on Jan. 1, 2020, if talks remain deadlocked.

But it’s becoming evident what Pyongyang wants most – and what it might be willing to do about it.

Last February, at the second summit between North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and U.S. President Donald Trump in Hanoi, Pyongyang made it fairly clear that negotiations over its nuclear program would go nowhere if an end to all U.S. sanctions weren’t on the table.

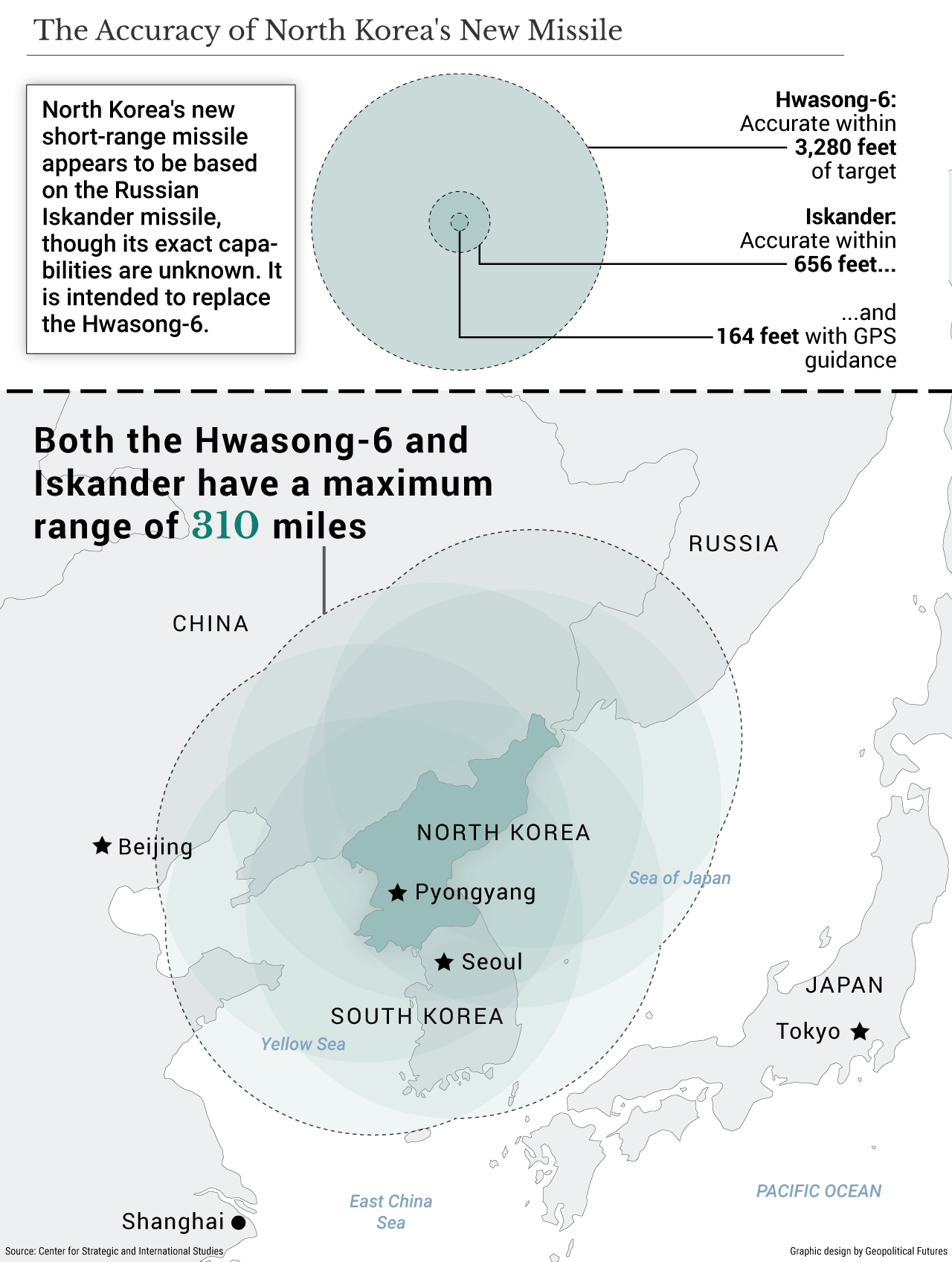

Since then, despite North Korea resuming tests of short- and medium-range missiles, the U.S. hasn’t backed off its “maximum pressure” stance, and talks have stalled.

In working-level talks in Sweden last month, the North Korean delegation walked out after less than a day, blaming the U.S. for “bringing nothing to the negotiating table.”

And when the U.S. and South Korea took the extraordinary step this week of postponing indefinitely major joint exercises in an act of “goodwill” – just the latest in several moves to scale back U.S.-South Korean military cooperation at Pyongyang’s behest – the North dismissed the gesture out of hand and rejected a U.S. offer for more working-level talks.

Bottom line: The U.S. can live with the status quo.

North Korea needs more and thinks it’s bargaining from a position of strength.

Get ready for a noisy 2020.

Why Pyongyang Is Looking To Shake Things Up

As we’ve argued several times, there’s never been much evidence that North Korea actually agreed to unilaterally denuclearize – at least, not in any of Kim’s speeches or in North Korean state media – as claimed by the Trump administration after the 2018 summit in Singapore.

In Pyongyang’s view, denuclearization means effectively the same thing as what the U.S. agreed to in 1968 when it signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which requires nuclear states to pursue disarmament at some point.

But so long as the North doesn’t resume testing of an intercontinental ballistic missile that could potentially deliver a nuke to the U.S. mainland, Washington can remain reasonably content with this reality.

And neither of North Korea’s ICBM tests in 2017 demonstrated that Pyongyang had mastered reentry technology – the most difficult part of ICBM development.

That’s why the North Korean issue has evidently been put on the back burner in Washington, which has had bigger and more immediate fish to fry, from China to the Middle East to worsening problems at home.

(Last month, when asked about Kim’s deadline, the U.S. assistant secretary of state for East Asian affairs admitted to being unaware of it.)

To be clear, the U.S. has extensive interests in seeing the North denuclearize.

A nuclear North has already led to a divergence of interests between the U.S. and its Northeast Asian allies, whose help the U.S. will want increasingly to manage China’s attempt to break free of its maritime constraints.

Over the past year, we’ve seen these strains materialize between the U.S. and South Korea, in particular, over conflicting strategies toward the North, as well as between Japan and South Korea.

But the problem for the U.S. is that, short of war, it’s hard to see a way in which the U.S. can force Pyongyang to capitulate and unilaterally disarm.

No amount of diplomatic isolation or economic pressure or offers of international integration will persuade Pyongyang otherwise, lest it risk regime security.

Thus, the most the U.S. can hope to achieve in negotiations is a permanent freeze on North Korean ICBM testing, some modest curbs on the size and makeup of the North Korean nuclear arsenal, and perhaps some mechanisms intended to contain Pyongyang’s aggressiveness as a newly confident nuclear power.

It’s standard North Korean negotiating practice to string negotiations along in perpetuity with empty promises and stall tactics.

But it’s not clear North Korea can live with the status quo indefinitely.

The North's foremost imperative is regime survival.

Its secondary imperative is paving the way for a reunified Korean Peninsula – which almost certainly would require the departure of U.S. troops from the peninsula.

Getting to hold on to its nukes in an implicit “freeze-for-freeze” arrangement with the U.S. serves both these aims.

But nukes alone aren't sufficient.

Kim’s “deadline” hints at as much.

The North’s most immediate need is sanctions relief. Kim Jong Un staked his regime’s legitimacy on economic development in a national address in April 2018, when he said the completion of nuclear deterrence would allow Pyongyang to focus fully on delivering newfound prosperity.

But his options for making good on this pledge aren’t great.

He could liberalize the economy and open the doors wide to foreign investment – and he’s been taking baby steps down this road.

But moving quickly here would risk a backlash from hardliners and elites in Pyongyang who’ve thrived on the status quo and, inevitably, weaken the regime’s control over the country.

He could solicit greater assistance and investment from more sympathetic neighbors like China and Russia, but he cannot force them to comply.

Both Beijing and Moscow have extensive strategic interests in at least limiting the North’s nuclear arsenal and, more important, deterring it from exploring just how much aggressiveness in the region its nukes let it get away with.

And both would need to be willing to open up another front in their myriad disputes with the U.S. – at a time when both are under mounting economic stress at home.

Pyongyang has ample historical reasons to mistrust both countries, anyway.

Kim’s third option – and the one most under his control – is to agitate more forcefully for the removal of the U.S.-led sanctions regime.

Success here would empower Pyongyang to open up the economy, but in a manner as tightly controlled as the regime feels is needed to manage the political risks at home.

Since early 2018, Pyongyang has hoped that by being on its best behavior and negotiating in good faith with the U.S., Washington would start to relax the sanctions on the regime or, even if the U.S. stayed the course, that enough other countries would be willing to defy the sanctions to render them largely symbolic.

This hasn’t happened.

Thus, North Korea has been signaling that it’s ready to try to take matters back into its own hands.

North Korea Gets Ready for a Show

The question of whether the North is really willing to resume long-range missile testing hinges on whether Pyongyang believes that doing so would risk provoking a military response from the U.S.

The U.S. has an imperative to protect the homeland from distant threats of that magnitude. A viable North Korean ICBM program would pose another problem to the U.S. alliance structure: The less South Korea and Japan believe that the U.S. is willing to defend them from North Korean attack if doing so puts the U.S. mainland at risk, the weaker the alliance.

Nuclear proliferation is inherently destabilizing, moreover, particularly with a regime like the one in Pyongyang.

It may never be rational for a country to conduct a nuclear first strike against a country capable of retaliating, but it would be perfectly rational to conduct a preemptive strike if a regime thought its own annihilation was imminent.

Pyongyang’s historical memory, its state-cultivated hair-trigger culture of paranoia, its suspect command-and-control systems, and the fact that it has been developing dangerous capabilities give it more reasons than most to believe it when an adversary threatens fire and fury.

Still, it will also have good reason to see any U.S. threats as mere bluffs.

As noted, the U.S. will be preoccupied elsewhere for much of the next year, including at home, with a contentious presidential election.

More important, short-range North Korean missiles can already likely strike U.S. bases in South Korea, possibly Japan and potentially even Guam.

China’s response to a U.S. military operation against the North, technically a Chinese ally, would also be unpredictable.

And maybe, just maybe, Pyongyang will have addressed the reentry problems that occurred with the ICBMs it tested in 2017.

Point being: A U.S. military operation would carry very high risks that arguably outweigh the threat posed to the U.S.

So, it's not hard to see the U.S. concluding that the only way North Korean nuclear-capable ICBMs are an existential threat to the U.S. mainland is if the North thinks a U.S. attack is imminent – and thus manageable through routine diplomacy and, say, by ending multinational exercises in the South that, from Pyongyang’s vantage point, are indistinguishable from preparations for an invasion.

The U.S. has long found ways to live with other nuclear-armed adversaries, after all.

Thus, a return to ICBM testing, or at least steps in that direction, can’t be ruled out if the U.S. doesn’t ease off its maximum pressure stance.

If and when this happens, the North will certainly have the United States’ attention once again.

It’s highly unlikely that, during the past year’s hiatus, the North has received or developed the reentry technology needed to complete its ICBM deterrent against the U.S., and so it’s unlikely to demonstrate as much.

But the only way to get there is to keep testing, and thus the U.S. will have a greater urgency to settle the matter.

Ultimately, the only realistic way out for the U.S. will be to call a spade a spade and start the process of settling for a deal that locks in North Korean testing but that falls far short of full North Korean denuclearization.

This would theoretically pose political complications for the Trump administration by further exposing the failure of his outreach to Kim.

But no U.S. president has succeeded in stopping the North Korean nuclear program, and several won reelection anyway.

The 2020 election won’t hinge on it, either.

Exactly how long it takes for the U.S.-North Korean deadlock to break very likely Will.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario