Uncertainty, Uncertainly, Uncertainty

by: The Heisenberg

Summary

- It's been 10 days since I last chatted with readers here. Spoiler alert: There's still no light at the end of the tunnel for the global economy.

- On the bright side, equities have managed to surge back near all-time highs, and I'm happy to give you some granular color on that.

- I'll bracket that with a 30,000-foot view on the global outlook and a 10,000-foot view (if you will) from the executive suite stateside.

- On the bright side, equities have managed to surge back near all-time highs, and I'm happy to give you some granular color on that.

- I'll bracket that with a 30,000-foot view on the global outlook and a 10,000-foot view (if you will) from the executive suite stateside.

The last time I chatted with readers here was on - checks notes, because it seems like a lifetime ago - October 14, in a piece called "Stephanie Kelton For President."

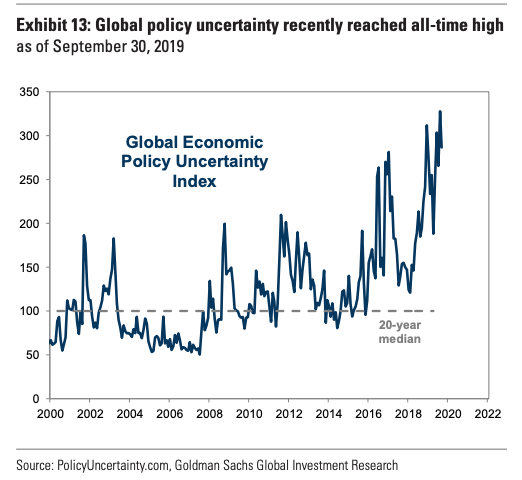

In that post (which Stephanie tweeted with a blushing emoji), I noted that expectations for global growth have continued to deteriorate in the face of record-high policy uncertainty and the seemingly intractable trade war between the world's two largest economies.

After citing the latest forecast cuts from the IMF and the OECD, I drew your attention to the latest edition of BofA's FX and rates sentiment survey.

When asked to choose from a variety of statements regarding the prospects for the flagging global economy, the 57 fund managers (who together control more than $800 billion in AUM) overwhelmingly chose "The global uncertainty shock has been so persistent that lasting damage has been done and policy action will be too little, too late."

In the 10 days since, there's been no shortage of fresh data to support the contention that the global economy continues to decelerate. There's been some decent news sprinkled in with the bad, but no top-tier data that I'm aware of (and I'm aware of pretty much everything) suggests there's a light at the end of this tunnel.

Allow me to just run through a few of the more worrying points, in no particular order. Some of these readers will be well apprised of, and others maybe not so much.

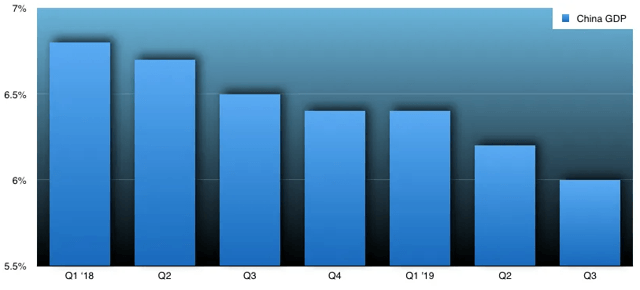

Most obviously, China reported the slowest quarterly GDP growth in some three decades last week.

The world's second-largest economy expanded 6% in the third quarter, below expectations (consensus was 6.1%).

September activity data (released concurrently) was generally better than expected, but that's not saying much.

For example, industrial output rose 5.8% last month, which sounds good versus consensus (4.9%), but has to be considered in context - August's 4.4% print was a 17-year low.

The raft of Chinese data out last week also included September trade numbers which found exports falling 3.2% and imports plunging 8.5%.

That latter figure suggests domestic demand is flagging in the face of the trade tensions.

As I noted elsewhere last Friday, a larger Chinese surplus due to flagging imports is the worst-case scenario from a global perspective - it effectively means the country is exerting downward pressure on already subdued global demand.

At the same time, the stimulus out of Beijing continues to come in dribs and drabs. The PBoC injected $28 billion in medium-term funds last week ahead of the GDP numbers, but when the third vintage of the revamped loan prime rate was released on Monday, it was unchanged from September.

Beijing implemented a broad RRR cut last month, and targeted cuts on October 15 and November 15, ostensibly help. But the pace of stimulus (both monetary and fiscal) has been maddeningly slow for those betting on Beijing to rescue the global cycle.

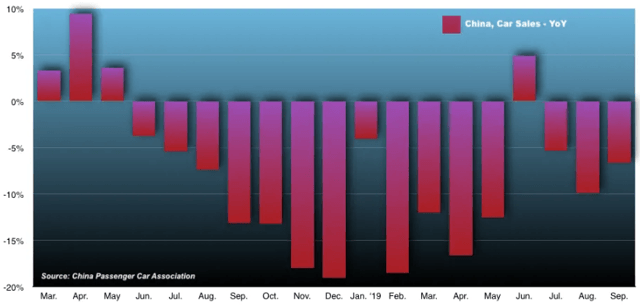

One notable chart in the context of the above shows sales of sedans, minivans and SUVs in China falling for 15 of the last 16 months. Deep discounts prompted one month of respite over the summer, but that’s it.

Data out of other countries tells a similar story.

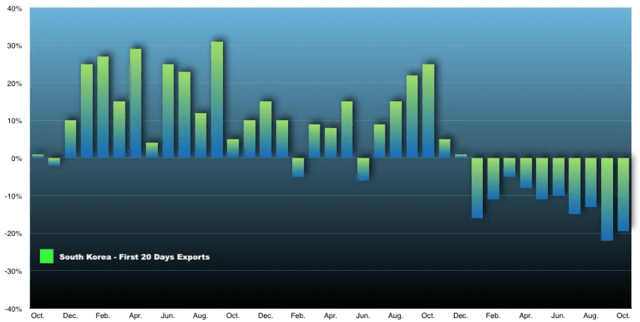

Bellwether South Korea, for instance, delivered another egregious first-20-day exports print on Monday.

Shipments in the first three weeks of October plunged 19.5% from the previous year, putting the country on track for an eleventh straight month of contracting exports.

Have a look at this:

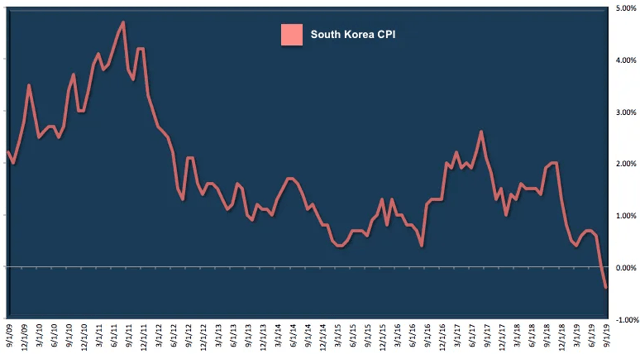

With apologies for the hyperbole, that is just plain, old horrible. Earlier this month, the BoK cut rates for the second time this year and although the bank did an admirable job of getting out ahead of things when it came to preparing the market for what, hopefully, will be just a brief trip below zero for consumer prices, it is nevertheless disconcerting that South Korea is now in deflation for the first time in recorded history.

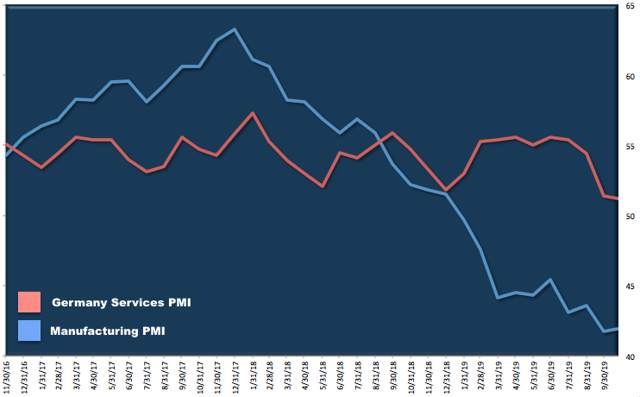

Moving on to Germany, most readers likely know the story there.

The world's fourth-largest economy almost surely entered a technical recession in the third quarter and thus far, Berlin has stuck to its guns when it comes to fiscal rectitude.

Rumblings about deficit-funded stimulus are getting louder, but so are the cries that by the time it comes, it will be too late.

On Thursday, flash PMIs for Germany betrayed a slight improvement from September, but the manufacturing slump is deep and entrenched.

Earlier this month, the German Economy Ministry slashed its growth outlook for 2020 to just 1% from 1.5% previously.

And I could go on.

Again, there are green shoots here and there (and if you ignore the employment subindexes, Thursday's Markit PMIs for the US weren't too bad), but the overall picture is clear. BofA described it in stark terms in a recent note.

To wit, from a piece out earlier this month:

Secular stagnation has now become our baseline. Growth is slowing in almost all major economies, in some cases from already low levels. Trade deals are only likely to avoid further tariff increases, at least for now, while keeping the tariffs of the last two years in place. Political uncertainty in the US is likely to increase ahead of the elections next year. We see increasing evidence that monetary policy has become ineffective, accumulating negative side effects. Fiscal policy is not coming to the rescue, and in any case, very few major economies could afford it. Structural reforms remain a theoretical and unpopular concept for most governments. Having to fight increasing populism, mainstream governments have often become reluctant to push for much needed reforms. Tight labor markets, in any case, suggest capacity constraints. Increasing wages without inflation also point to risks for profits.

In the first linked post above (the Kelton piece), I suggested that MMT-like policies are almost surely in the offing, as they are popular (in one variant or another) among populists on both sides of the political spectrum. Right-wing populists aren't likely to embrace Modern Monetary Theory by name, but they will (and, indeed, they already have in the US) in practice.

Of course, none of this has stopped US equities from scaling close to new highs in October.

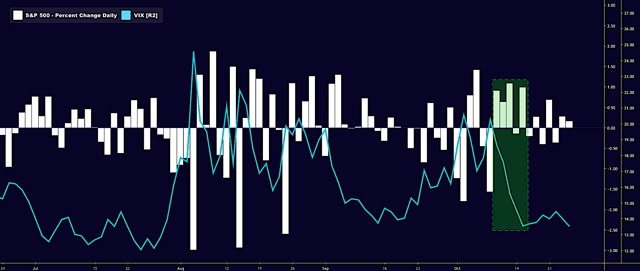

If you wanted to explain the mid-month "melt-up" in US stocks highlighted in the visual below, it wouldn't be very difficult.

For weeks, folks had been "long" worst-case scenario expressions and "short" good news, a thesis which eventually collided head-on with two macro catalysts in the "Phase One" Sino-US trade "deal" and unexpected progress towards a Brexit agreement.

Leaving aside the nebulous nature of the former and the fact that the latter is still hanging in the balance (Boris Johnson is now angling for a December 12 election in the event he can't get his Brexit deal crammed through by November 6), movement on both trade and Brexit hit amid heavily lopsided positioning (dealers had hedged what they were short to clients in terms of crash protection).

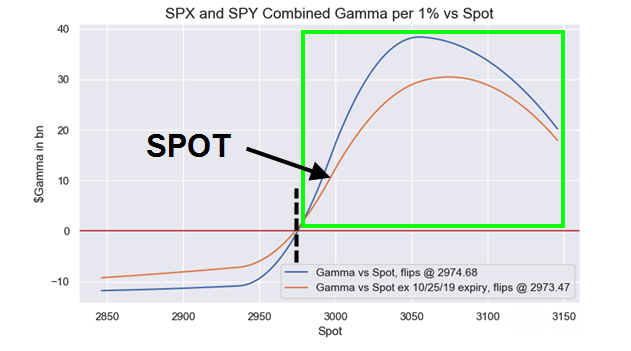

"The dealer 'crash' hedge purge as the flow catalyst into the monthly 'Gamma Event' that is expiration has been a second-order slingshot for stocks over the past week-and-a-half," Nomura's Charlie McElligott wrote late last week, adding the following crucial color on the mechanical catalysts behind the move:

This multi-day rebalancing out of front and into the 2nd contract by Wednesday—on top of Dealers puking a meaningful amount of the VIX upside / VIX futures exposure which they had to buy in order to hedge the “Oct Call Wing” buyer flow that they were short to clients and each other—is the real “how and why” of this rally and the stickiness of Stocks holding “higher,” despite the constant complaints from those who believe we should be lower for “fundamental” reasons.

That's from a note dated Friday, October 18 (I emphasize that so readers have a reference point for his mention of "Wednesday" and "the past week-and-a-half").

There's a tactical trade coming out of that, which I don't want to delve into in any great detail for fear of encouraging readers to attempt things they probably have no business attempting.

But, in the interest of adding a bit of additional color to the above, I will give you a brief quote from McElligott's latest note (dated Wednesday) which captures the thrust of it:

As I referenced last week with the VIX “knee-capping” we’d been calling-for into expiry (which then drove a massive steepening of the VIX futures curve, as longer-dated stays “bid” against VIX ETN rebalancers SMASHING front-month thx to the contract roll), the trick is that this ETN rebalancing impact on “lower VIX into expiry / settlement” then marks a “local low” which tends to see a 1) higher VIX- and 2) VIX curve flattening- (or even inversion) impulse thereafter.

Meanwhile, equities are now pinned, as it were.

(Nomura)

(Nomura)

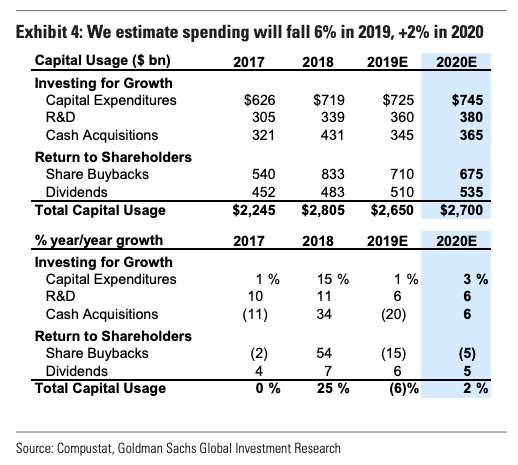

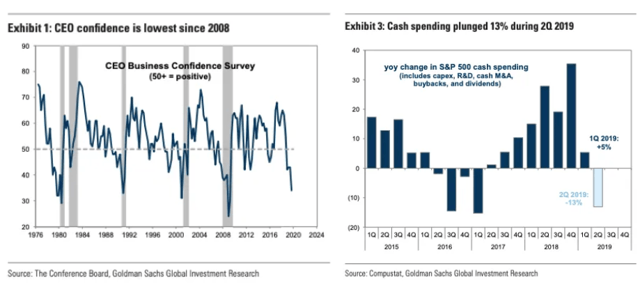

Trudging out of the deep weeds and panning quickly back to a 10,000-foot view (but not quite to the 30,000-foot level we started from here at the outset), CEO confidence in the US has plunged to crisis-era levels (left pane below).

That, in turn, has weighed heavily on cash spending, which dove double-digits in the second quarter of 2019, after hitting records the previous year.

Behind plunging executive confidence is rampant uncertainty, attributable in part to trade tensions.

Here's Goldman (NYSE:GS), from a note dated October 17:

Companies spend less cash when policy uncertainty is high. Historically, growth in aggregate S&P 500 cash spending has been weaker during periods of high policy uncertainty. The combination of an ongoing trade conflict and next year’s US presidential election will likely result in lingering uncertainty.

The outlook for cash spending isn't great, although it's not terrible either. The year-ahead numbers are, of course, just projections, but the rationale behind them (i.e., the self-evident notion that more uncertainty makes management teams less willing to spend) and the fact that the 2019 estimates reflect some numbers that are already on the board (e.g., the steep drop-off in Q2 shown in Exhibit 3 above) make them well worth highlighting:

We estimate cash spending will fall by 6% during 2019 before rising by a modest 2% during 2020. S&P 500 cash spending rose by 5% during 1Q, but plunged by 13% yoy during 2Q. During 2019, the decline in spending will be driven by a 20% drop in cash M&A and a 15% fall in buybacks. In 2020, we expect modest growth in capex (+3%), R&D (+6%), dividends (+5%), and cash M&A (+6%) will be partially offset by a 5% decline in share repurchases.

Note that Goldman sees gross buybacks falling 5% in 2020. The bank cites dramatically lower cash balances, sluggish earnings growth and political scrutiny of corporate cash usage as factors likely to weigh on management teams’ capacity and willingness to buy back shares.

Obviously, buybacks have supported US equities over the past several years. Good people can debate the extent to which that support has been responsible for rescuing the market during acute downturns and smart investors can argue about how much share repurchases actually matter when it comes to inflating corporate bottom lines and thereby share prices. What isn't debatable, though, is that buybacks do have an impact and they are set to wane going forward.

Taken as a whole, all of the above suggests that from a macro perspective, the only three words that matter are "uncertainty," "uncertainty" and "uncertainty."

And don't let anyone try to use the old "there's always uncertainty" line on you, if the goal is to somehow trivialize just how indeterminate things are. For one thing, many of the readily accessible non-market-based measures of uncertainty at our disposal are sitting at or near all-time highs. The EPU is one example (there all manner of variations which you can access here).

(Goldman, EPU)

(Goldman, EPU)

Beyond that, common sense tells you that these are particularly trying times. Just watching the news is enough to stress the average investor out. Imagine if you were a CEO.

In addition to the trade frictions, the ongoing impeachment inquiry in D.C. is now highly relevant for investors and corporate America. Donald Trump will almost surely be impeached by the House. That is just an objective assessment. If you don't believe pundits and historians or you can't do the math yourself, just ask the crowd (i.e., just look it up on PredicIt here).

The real problem, though, is that the Syria debacle raises the odds of a Senate conviction from zero previously to a number higher than zero, even if that number is still infinitesimal.

When you throw in the fact that Elizabeth Warren is just as likely as not to beat out Joe Biden for the Democratic nomination, the level of political angst among professional investors, and certainty among CEOs and CFOs, is very elevated, even if the average investor is more insulated from all of this by virtue of not having as much to lose.

Although nobody knows what's coming, we do know what people would like to see to alleviate some of their concerns.

For one thing, the trade war needs to end - like, yesterday. As is the case with Brexit, the market is exhausted with trade headlines.

And yet, it appears as though the Trump administration and China are set to do this dance for years as multiple "phases" of a prospective agreement materialize at unpredictable intervals.

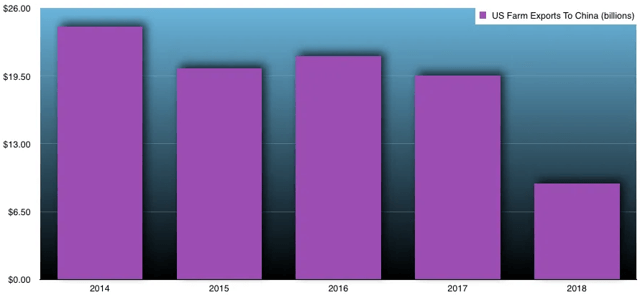

Just Thursday, Bloomberg reported that China may be willing to buy $20 billion in US farm goods during year one, as part of "Phase One," but will only hit the $40 to $50 billion figure cited by President Trump in year two, under Phase 2 (or 3), when tariff relief is expected.

Underscoring the extent to which this has become something of a hamster wheel is the following chart which shows that if China does ramp farm purchases back up to $20 billion, that will only get us back to levels seen in 2017, before the trade war started. So, all of this for what, exactly?

The other thing that has to happen for the outlook to improve materially is that somebody (where that means either China or Germany) needs to step on the fiscal gas pedal.

As outlined above, it seems like we are some way away from seeing Beijing and/or Berlin embark on an aggressive, "kitchen sink" stimulus push.

The longer that takes, the more vulnerable the world will be to negative headlines, especially those with a direct connection to the global economy.

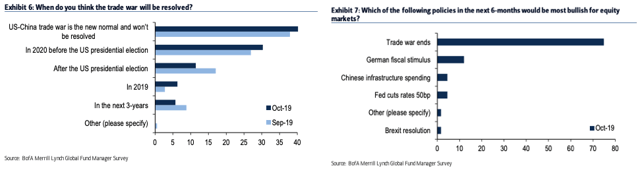

And with that, I'll leave you with two passages and two charts from the October edition of BofA's closely-watched Global Fund Manager Survey. To wit:

Ongoing bearishness about the prospect of a trade war resolution: note 43% of FMS investors think the US-China trade war is the new normal vs. 36% who think we will see a resolution before the 2020 US Presidential election.

Aside from the end of the trade war (#1 FMS “tail risk”) FMS investors think a German fiscal stimulus package, a 50bp cut by the Fed or a Chinese infrastructure package would be the most bullish for risk assets over the next 6 months.

(BofA)

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario