The fool’s gold of emerging market valuations

By: Guest post

Lawrence Hamtil is an investment advisor at Fortune Financial Advisors in Overland Park, KS. He writes frequently about investing topics on the firm’s blog. His research and commentary have been cited in several major financial publications. The information provided in this publication is for general information only, and is not intended to provide specific recommendations.

For many years now, the value investors at Grantham, Mayo, and van Otterloo (also known as GMO) have been bullish on emerging market equities.

Jeremy Grantham, the firm’s chief investment strategist, famously suggested that a hypothetical fund manager for Joseph Stalin would stand his best chance of not being shot for poor results by investing substantial capital in EM.

“Be as brave as you can on the EM front,” he said. “Be willing to cash in some career risk units. Bravery counts for so much more when there are very few good or even decent alternatives.”

Last week, GMO again made its case for EM, with Rick Friedman from the Asset Allocation team arguing that EM equities are as appealing as ever, given they are as cheap as they have been since the heady days of the tech bubble:

Certainly, if one were to take only the index-level valuations, EM, as measured by MSCI, would look like a steal. EM trades at just under 12 times next year’s earnings as of September, versus more than 17 times for the US

Yet take a look beneath the surface of index-level data and you could argue that emerging market stocks are hardly the bargain that they seem to be.

To start, let’s break down the EM index into various sectors. On this basis, EM often trades on a par with, and in some cases even at a premium to, its US counterparts. To this point, here’s a table of the valuations of the various sectors on both forward and trailing earnings:

It’s clear from these data that the bulk of the EM discount resides in a few sectors which are generally associated with domestic revenue streams, such as banks and utilities, and in energy and materials, which are often dominated in their markets by state-owned enterprises.

However, even then, the sector-level data mask serious differences between the businesses in each sector. For example, materials in the US is dominated by chemicals firms, while mining dominates the EM materials sector. It makes sense, then, to look at some industry-level data to see where these valuation discounts are.

Indeed, if you look at what one might characterise as the more globalised industries like software, beverages, and automobiles, there are actually very few valuation differences between the US and EM:

In contrast, within the more domestically-reliant industries like banks and utilities, there are significant valuation differences between the US and EM:

It is likely, then, that any strategy that focuses on the cheapest stocks in the EM universe would be heavily based on this latter group. That is certainly the case for MSCI’s EM Value index, where financial, energy, and materials stocks currently combine to make up just under 60 per cent of the index.

GMO also cites a favourable cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings rate (CAPE) to make its case for EM. As Mr. Friedman notes in his article, EM CAPE is at 15 times versus a lofty 29 times in the US

It is true that the CAPE ratio has certainly been a reliable tool for forecasting real equity returns in both the US and EM, but, as Joachim Klement of Fidante Partners observed in 2012: “[I]t is clear that emerging market stocks can only outperform developed market stocks if their respective currencies continue to appreciate versus the US Dollar or other developed market currencies.”

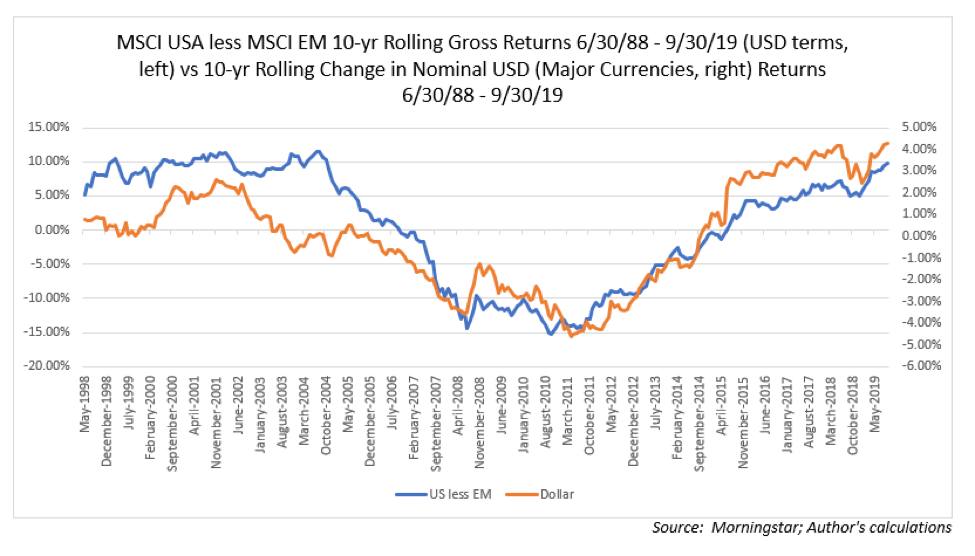

For a US investor, this is a critical point; over the decades since MSCI’s EM index began in June of 1988, excess returns for EM relative to the US have coincided with significant dollar weakness:

As you can see from the chart, the great EM bull market (relative to US stocks) of the 2000s coincided with a substantial bear market in the dollar, and its end coincided with the resurgence of the greenback circa late 2011.

Mr. Friedman does acknowledge the dependence of excess EM equity performance on USD weakness, but suggests EM currencies are currently positioned favourably to the dollar, which GMO believes is due for a period of weakness on a relative basis.

I’m no expert in currency valuation, so I am agnostic on this point, but it seems a rather tall order to have one’s equity bets so reliant on something as fickle as the currency market.

The final argument Mr Friedman and his colleagues make is that because of their cheaper valuations, EM equities are poised to hold up better than expensive US stocks, just as they appear to have done in the aftermath of the tech bubble (in their analysis, GMO measures performance over the four years ending in January 2004):

As I have argued before, this particular period of index returns had more to do with the excessive tech weighting in the S&P 500 index at as the bubble popped, as well as a decline in the dollar, than it had to do with EM being cheap.

For example, over the same period cited by GMO in the chart above, while both MSCI EM and MSCI EM Value did outperform their respective MSCI USA counterparts, EM tech performed almost as poorly as US tech, just as US energy performed well, though it did lag its EM counterpart.

Perhaps most tellingly, over this period the equal-weighted version of the MSCI USA index outperformed the equal-weighted EM index, which suggests the excess performance cited by GMO was due to imbalances in sector composition (a lot of tech and little energy in the US versus little tech and a lot of energy in EM). EM energy, of course, benefits from a weaker dollar as energy stocks, particularly with the tailwind of rising oil prices, trade inversely to the dollar:

To conclude, it is difficult to share GMO’s enthusiasm for emerging markets.

In addition to not being as cheap as they appear, the majority of EM markets are overly concentrated in financial stocks, and they are subject to large drawdowns due to political and fiscal instability, among other things.

It is even debatable whether EM stocks, using the generic MSCI EM Index as a proxy, add any material value to diversified portfolios, as I have argued previously.

GMO’s EM trade may end up working out very well for them and their clients but, in my opinion, the thesis requires too many external factors to work to make it worth the risk.

Home

»

Emerging Markets

»

Investment Strategies

» THE FOOL´S GOLD OF EMERGING MARKET VALUATIONS / THE FINANCIAL TIMES

sábado, 23 de noviembre de 2019

Suscribirse a:

Enviar comentarios (Atom)

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario