In South America, US Influence Faces a Backlash

By: Allison Fedirka

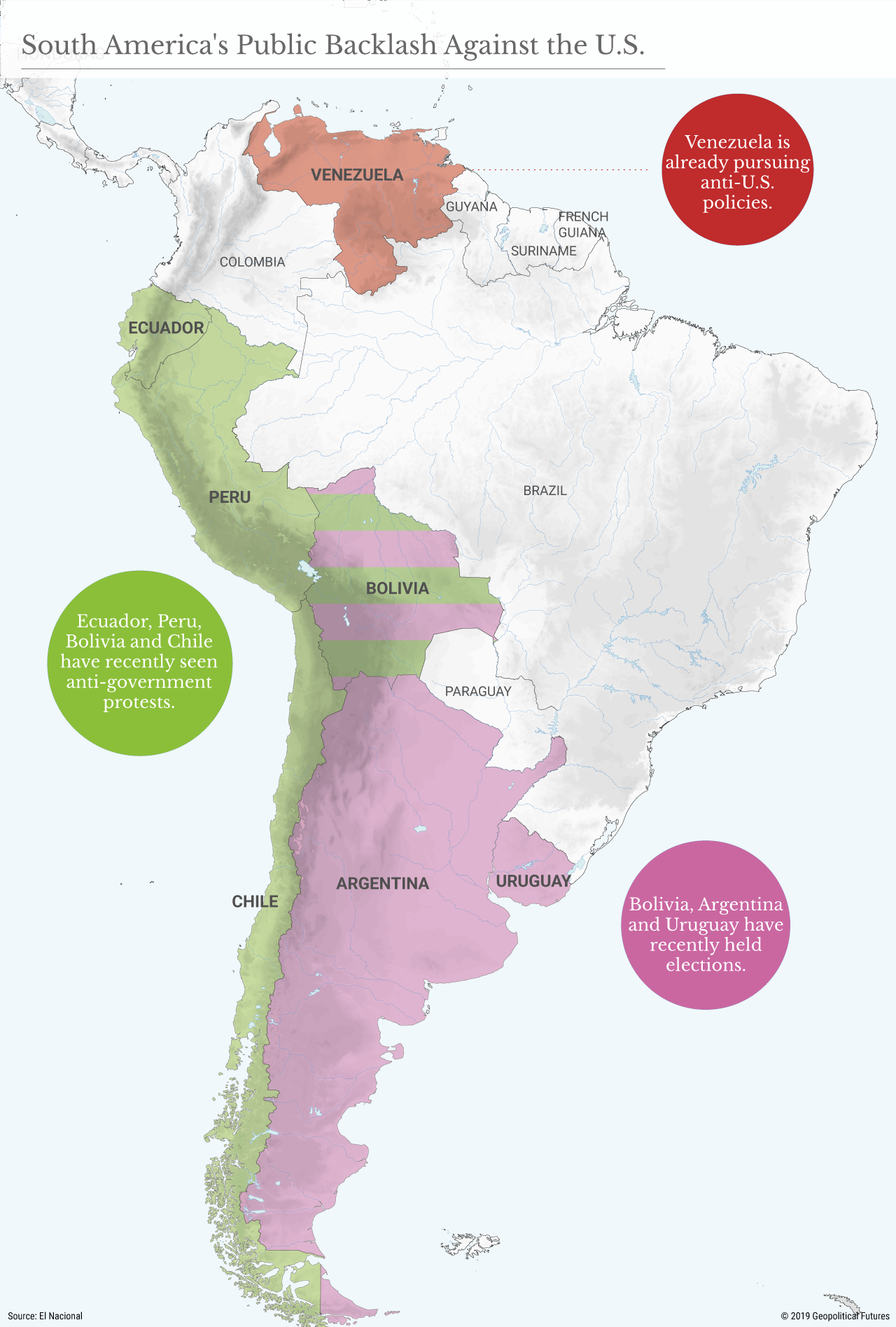

With a global economic slowdown looking increasingly inevitable, it’s time to turn from what’s driving that slowdown to what impacts it will have. Among the most important impacts is social unrest, as embodied in recent anti-government protests in South America – including in Chile and Ecuador.

As the global economy slows, wealth disparities will be thrown into sharper relief, and citizens’ demands on governments to provide for them will grow.

Governments unable to meet these demands or sufficiently justify their policy approaches will continue to be challenged by the people.

This will undoubtedly have domestic consequences – but it’s also worth exploring the impact this will have on international ties.

In South America, anti-government citizen protests will call into question the United States' role, influence and relations in the region.

Within nearly every South American country there is a fault line between an open-market, fiscally conservative camp on the one hand and a controlled-market, pro-social spending camp on the other.

The two sides’ positions naturally align them with different international powers that follow similar economic orders: the first with the United States and the second with countries like Russia or China.

This means that when South American countries implement austerity measures, protesters tend to lash out against their governments for following U.S.-designed policies.

Consequently, this creates a backlash against the U.S. and a space into which extra-regional powers like Russia can advance their positions in the region.

The U.S. and the Global Economy

The United States has, needless to say, played a pivotal role in shaping the global economic order for the past 75 years.

The U.S. ranked as the world’s single largest economy for the entire 20th century and into the 21st. Its 2019 nominal gross domestic product totals $21.44 trillion, accounting for nearly a quarter of the global economy, according to the most recent International Monetary Fund figures.

But U.S. economic influence goes beyond the sheer size of its economy. In the wake of World War II, much of the global economy faced two major challenges – reconstruction and avoiding yet another repeat of such a catastrophic conflict.

The United States found itself in the unique position of having been a combatant in the war but without having large swaths of its economic hubs destroyed by it.

This afforded Washington the opportunity to heavily influence the postwar reconstruction of international monetary and trade systems.

These systems were laid out in the Bretton Woods Agreement, which was based on the premise that equal terms for trade and international economic collaboration would help secure prosperity and peace.

In practice, it helped regulate exchange rates, curtail speculative capital flows, promote foreign direct investment and discourage the formation of closed, controlled trade blocs.

Bretton Woods underpinned the operational framework for major world economies – with smaller allied economies in tow – for nearly three decades.

Even after the Bretton Woods system formally ended, its key institutions remained in place, along with sustained U.S. influence in global economic policy.

Both the IMF and what is now the World Bank came into existence under Bretton Woods.

The IMF currently serves as the lender of last resort to countries in financial trouble in an effort to help stabilize the global economy. Its aid is often conditioned on countries meeting specific criteria, which are often aligned with U.S. views and priorities.

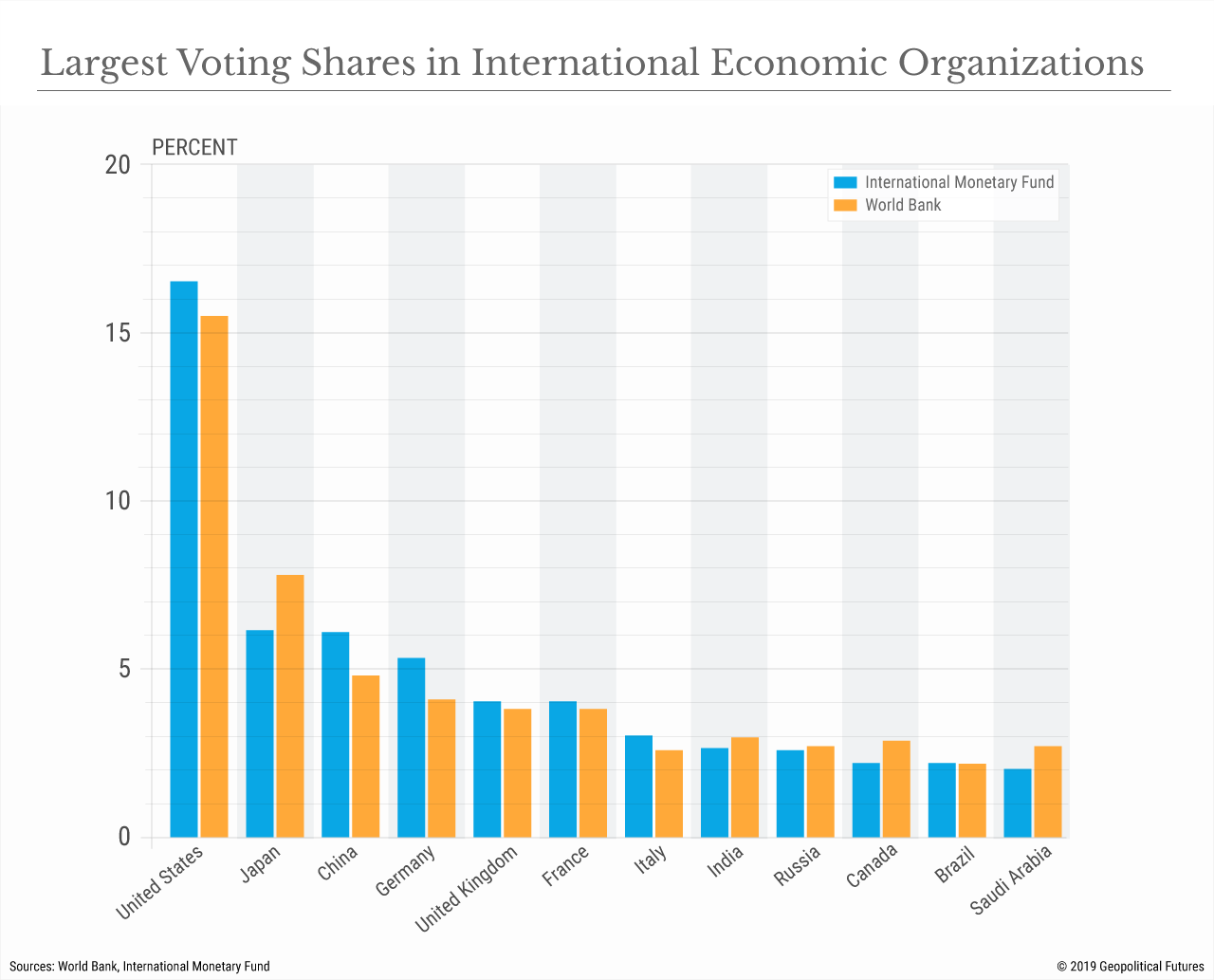

The U.S. also has a larger voter share in the IMF than any of the other 189 member countries.

Amendments, reforms and other decisions require 85 percent support to pass, and while the U.S. cannot fully control the IMF, its share of the votes is large enough to give it effective veto power over any action the fund may try to take, putting the U.S. in a position to direct the general course of the IMF.

The World Bank evolved out of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the institution that funded Europe’s reconstruction.

It serves as a major source of development assistance to lower-middle-income and low-income countries. As with the IMF, the U.S. has the highest share of votes of any country.

In addition, the U.S. dollar remains the global currency for commodity trade and prices.

The U.S. also has immense sway over the behavior of other countries – for instance, by using the SWIFT money transfer system to enforce economic sanctions on other entities.

Though Russia and China, among others, are making attempts to stand up alternatives to these U.S.-tied mechanisms, they are still a long way from being direct or equal substitutes.

In South America, the United States’ impact on national economies and individual livelihoods goes well beyond the general influence it has in the global system to include specifically prescribed and designed policies.

As the Third World debt crisis unfolded in the early 1980s, many countries in the region found themselves in need of loans, investment and help servicing debt.

In what became known as the Washington Consensus, institutions such as the U.S. Treasury Department and the IMF offered a solution: South American countries could adopt policies of fiscal reform, privatization, market deregulation and free-market trade in exchange for loans and investments.

After a decade, however, it became clear the United States’ recipe for success in these countries was not producing the desired results, and many participant countries felt the U.S. had left them in the lurch.

Critics who argued the policies did more harm than good managed to push out the governments that had accepted the Washington Consensus.

The entire process sowed seeds of resentment and doubt over U.S.-led economic policies among political parties across South America.

How the Economic Becomes Political

Most South American economies are characterized by political cycles where power alternates between governments favoring free-market economic policies and those advocating more interventionist, social-spending policies.

This feature is rooted in their colonial pasts, dependence on exports of raw materials and past experiences with U.S.-driven economic policies.

As a result, domestic discussions over economic models and policies are closely linked with the question of whether to accept or reject political alignment with the United States.

A free-market economy is often associated with a pro-U.S. stance, while a highly controlled, high-social spending economy tends to have a more antagonistic stance toward the U.S.

Swings between cycles have become particularly pronounced in the past 20 years as part of the prolonged fallout from the Washington Consensus.

A significant anti-U.S. wave swept through the region at the turn of the century.

After 15 years, there were signs of this tide ebbing as more pro-market, pro-U.S. leaders were elected.

But slowing global economic conditions have changed matters.

First, it triggered greater scrutiny of governments, the services they provided and their use of funds.

Second, people became more focused on their quality of life and living conditions, especially as those conditions started to decline.

Last, it renewed the debate over whether these countries should continue following their current policies or adopt new ones to better deal with the economic problems they’re facing.

As economic pressures intensify, the polarization between the two sides of the cycle becomes more apparent, relations grow more strained and unrest more common.

And, as the slowdown continues, there is a higher risk of backlash against the U.S. and increasing opportunities for powers outside the Western Hemisphere to expand their political influence in the region.

Doubts, critiques and debates over the Washington Consensus are sharp in the region’s recent memory.

In light of the slowing global economy, they’ll be revived as countries consider the U.S. role in driving the current decline and which economic policy path to pursue.

There are active political camps in a number of these countries that reject the neoliberal U.S. model and demand more spending and action from their governments to address economic shortcomings.

As segments of the population reject their governments’ U.S.-aligned economic policies, space will open for other actors, particularly Russia and China.

This opening will be primarily political; economic ties can play a supportive role but won’t be foundational, since a global slowdown means even major powers will have more limited resources that they’ll need at home.

Similarly, security ties will be symbolic at best. But the political sphere is ripe for the taking and promises the greatest potential return for outside powers.

Realignments to Watch For

Russia has already started to capitalize on this opportunity, focusing so far primarily on the Caribbean.

There are two advantages for Russia in focusing its time and attention here.

First, its proximity to the U.S. is valuable to Russia.

Second, Moscow has Cold War ties in this region that it can tap into.

Russia’s economic and security interactions, primarily concentrated on Cuba and Venezuela, reflect a pragmatic approach that takes into consideration Moscow’s economic constraints and a desire to avoid any major conflict with the U.S.

Russia’s interest in Venezuela’s energy sector has shifted to focus on acquiring strategic hard assets and revenue-generating endeavors, while it phases out less strategic and unprofitable projects.

Similarly, on defense Russia continues to honor past agreements and promote political and technical exchanges but has reigned in things like loans and credit to buy more Russian military equipment. In Cuba, Russia has put forward funding for small projects to help boost the island’s economy but resisted any high-cost initiatives such as providing the island with discounted fuel to make up for losses resulting from Venezuela’s decline.

China, on the other hand, faces a more challenging path given that its ties with South America have been mainly economic and commercial.

The trade war with the U.S. and China’s domestic economic pressures have forced Beijing to be more selective and pragmatic about its economic engagements in South America.

But current conditions also make developing political ties more attractive.

Until recently China was able to offer countries like Venezuela and Ecuador generous loans with favorable terms in exchange for commodities, usually oil.

This approach has been phased out because of falling oil prices and increased uncertainty over loan repayments.

Trade and investment, the other pillars of Chinese engagement in the region, will also come under increased scrutiny during the slowdown.

South American trade with China includes large volumes of raw materials and natural resources.

Slowing demand and the likelihood of lower commodity prices will pressure South American countries to trade more value-added goods, which is a hard sell in China.

While China still has hundreds of billions of dollars available for foreign investments, its internal slowdown and mounting debt have already forced it to be more selective with who it gives funding to and make an extra effort to assure partners that those funds will actually appear.

Overall, then, this puts China in a good place: The opening of political space in parts of South America will coincide with China’s need to put more emphasis on political relationships as the economic ones face more constraints.

South American governments’ oscillation between polarized economic policy platforms, coupled with those policies' close ties to U.S. relations, creates a distinctive regional reaction to the global economic downturn.

The pursuit of economic policies aligned with U.S. and IMF principles is fiercely at odds with an alternative, more socialist approach.

In the event that countries reject the U.S.-aligned policies – and current protests and elections suggest that is a real possibility – there will be an opening for outside actors like Russia and China.

These actors will also be vulnerable to an economic slowdown, but their desire to build stronger political ties becomes an alternative to potentially reduced economic investment that neatly coincides with the current dynamics of the region.

The degree to which Russia and China can build political influence and maintain that hold will depend on a host of variables.

But at this point what is clear is that the current environment makes public backlash against the U.S. likely – and that, at the very least, opens the door for Russia and China.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario