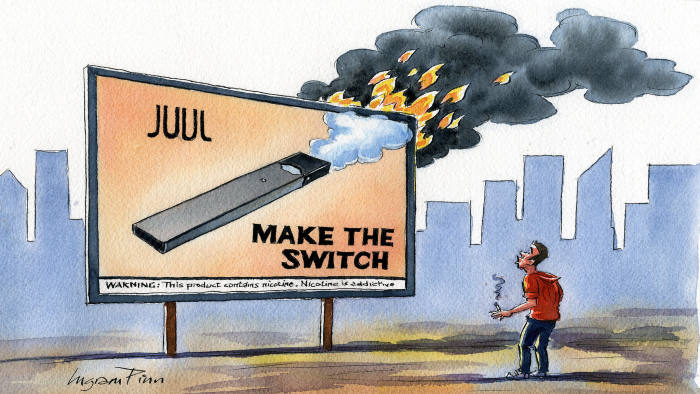

The US is in danger of lurching from lax oversight of vaping to banning it unwisely

John Gapper

© Ingram Pinn/Financial Times

The crisis at the US vaping group Juul that contributed to the collapse of a possible $200bn merger between Altria and Philip Morris International is another example of a fashionable disrupter of a traditional industry faltering. WeWork has shelved its initial public offering and Juul’s $38bn valuation is evaporating.

But Juul’s troubles, which led to its chief executive being replaced last week, are not merely a financial shock to its investors, including Altria. The company’s misbehaviour could cause public health damage by sparking a broad US crackdown on the best alternative to smoking so far, apart from giving up nicotine entirely.

The US is in danger of lurching from an overly permissive approach, which encouraged vaping to spread among teenagers, to barring e-cigarettes. Asian countries are already imposing bans.

Neither is the best way to regulate vaping and to wean citizens off their dangerous addiction to tobacco.

The trouble started with a teenage craze that led to 21 per cent of US high school students inhaling nicotine through devices at least occasionally last year. Like other countries, the US prohibits television and other kinds of advertising for cigarettes, but it allowed Juul and others to advertise e-cigarettes widely, and to enlist celebrities and social media influencers.

The damage done by this loophole was compounded by lax regulation. Juul was permitted to sell higher strength pods in the US than in Europe and to add flavours. Although US retailers are barred from selling e-cigarettes to under-18s, 80 per cent of Juul’s US sales are estimated to come from teen-friendly flavours such as mint.

It became a crisis with the discovery of 805 (and counting) cases of unexplained lung injuries among vapers, including 12 deaths in 10 states. That led to a warning by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for all Americans to consider stopping vaping. Walmart has stopped selling e-cigarettes, San Francisco has prohibited sales, and states are leaping into action.

Parents are understandably worried about their children becoming addicted to nicotine, and fears are growing that vaping will turn out like cigarette smoking: a habit that seemed benign in the early days, but turned out to be very dangerous. Some 480,000 people die every year in the US from smoking-related diseases.

But nicotine vaping does not appear to be the cause of most of the recent lung injuries. The CDC disclosed on Friday that 77 per cent of the cases it analysed involved people who had used devices to inhale the cannabis compound THC.

THC is often mixed by street sellers of cannabis vapes with Vitamin E acetate, an oil that can irritate lungs and cause a form of pneumonia.

Only 16 per cent of patients claimed to have inhaled only nicotine vapour, which is water-based and contains few chemicals, compared with an estimated 7,000 chemicals in tobacco smoke. “There is some risk with nicotine vaping but the health benefits of reducing smoking hugely outweigh it,” says John Britton, director of the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies.

The UK’s Royal College of Physicians estimates that nicotine vaping could carry 5 per cent of the health risk of smoking in the long term. This is equivalent to 24,000 deaths per year in the US if every smoker vaped instead (and had never smoked). It would be a heavy toll, but tiny compared with smoking.

The best public health outcome remains to persuade as many adult smokers as possible either to give up cigarettes, or limit their risk by switching to vaping nicotine from regulated suppliers. That means keeping e-cigarettes available for sale while trying to prevent young people from taking up vaping and becoming addicted to nicotine, with the risk of later turning to smoking.

This strategy has worked quite well in European countries including the UK, despite the US crisis. Cigarette smoking is in long-term decline and while 3.6m British people now vape, only 6 per cent of them never smoked. Meanwhile, only 1.6 per cent of 11 to 18-year-olds vape more than once a week.

Unlike in the US, e-cigarette advertising is banned in Europe and an EU directive in 2014 set stricter standards for the regulation of vaping. European countries including Finland have barred flavours, and regulators have not faced the same political backlash as the US Food and Drug Administration.

The FDA has changed course under pressure. It wrote a warning letter to Juul last month asking it to justify claims that vaping is safer than smoking and accusing it of ignoring the law. That begs the question of why the FDA has not found out for itself, and why so much marketing was allowed.

The danger is that the US compensates for past laxity and cracks down so heavily that it snuffs out proper uses for e-cigarettes; vaping companies face a deadline of next May to submit existing products for approval. Outlawing vaping would be easy, but the side effect would be heavier smoking.

Amid fears about the spread of teen vaping, it is easy to miss another vital statistic: the number of US adult cigarette smokers fell by 9 per cent in 2017 as people gave up or found alternatives.

Something is going right.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario