The People’s Bank of China doesn’t want easier monetary policy to flood the housing market with fresh credit, as happened in 2015

By Mike Bird

Like President Trump, China’s leaders want lower interest rates. The constraint they face isn’t an independent central bank but a bubble-prone property market.

This week, the People’s Bank of China revealed a long-anticipated change to how commercial bank interest rates will be calculated. Revealingly, PBOC officials were at pains to stress that while the move might lower interest rates for corporate lending, mortgage interest rates wouldn’t fall.

Eighteen banks now have to show the PBOC the best interest rates they offer to their clients, based on rates set by the central bank’s medium-term lending facility, a source of credit for the banks themselves.

The change has two objectives. One is to lower rates, at least for some loans. Previously, the banks had to base their lending rates not on the MLF but on China’s benchmark rate, which is roughly a percentage point higher for one-year loans. The other is to improve the transmission mechanism for monetary policy: The PBOC wants banks to do a better job of passing changes in policy on to their customers.

The reform is described widely as a market-oriented liberalization, but it isn’t entirely clear why. The PBOC is making banks calculate their lending rates based on one interest rate it administers, rather than another interest rate it administers. Rates for the one-year MLF have barely changed in the past three years.

The most interesting aspect of the PBOC’s new approach to interest rates is the deliberate exclusion of real estate. Photo: wang zhao/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

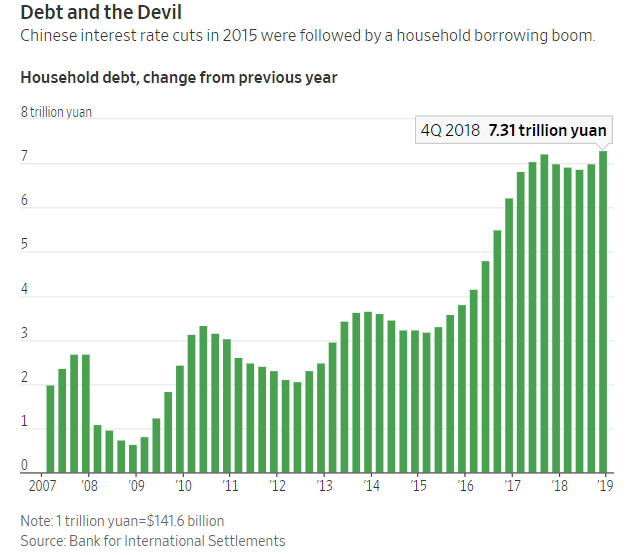

The most interesting aspect of the new approach is the deliberate exclusion of real estate. This is likely because Chinese households went on a borrowing spree after the PBOC’s 2015 round of benchmark rate cuts. In 2016, household debt rose by 6.2 trillion yuan ($878.11 billion)—compared with an increase of around 3 trillion yuan a year on average for the previous five years—and only accelerated subsequently.

Beijing is also aware of the other lesson from its last round of interest-rate cuts: They helped send the yuan sharply lower, in turn triggering capital outflows. The PBOC may be comfortable with the yuan trading past 7 to the dollar, but a much weaker currency isn’t its ambition. The fact that the new lending guideline was set at 4.25% on Tuesday, just fractionally below the 4.31% under the old system, suggests hesitancy on the part of policy makers.

This week’s announcements are more a reflection of China’s limited monetary options than a grand effort to liberalize how credit is dished out. The PBOC’s existing tools can’t be deployed without generating the same worrying imbalances as last time.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario