Mark It Zero

by: The Heisenberg

Summary

- Friday was a wild ride, and it continued after the closing bell on Wall Street.

- Investors are now left to ponder both the short- and longer-term consequences of the latest Fed and trade drama.

- Here are some thoughts on what happens next both for markets and for policy.

- Investors are now left to ponder both the short- and longer-term consequences of the latest Fed and trade drama.

- Here are some thoughts on what happens next both for markets and for policy.

After the closing bell sounded on the fourth consecutive week of losses for the S&P, President Trump responded to China's retaliatory tariffs.

The tariff rate on the $250 billion in Chinese goods which were taxed at 10% from September 24, 2018, and from 25% after the White House abandoned the Buenos Aires truce in May, will be taxed at 30% starting on October 1. Additionally, the tariff rate on the $300 billion in Chinese goods which were set to be taxed from September 1 and December 15 (Trump delayed duties on some items in an effort to avoid hurting US consumers ahead of the holiday shopping season) will be 15% instead of 10%.

Delaying the announcement until after the close on Wall Street was clearly an effort to avoid triggering further losses. The S&P fell more than 2.5% on the final day of the week.

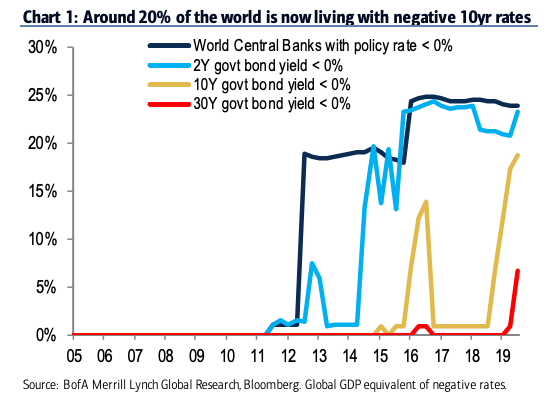

The worst, second-worst and third-worst days of 2019 for US equities have all come in August.

Here's an updated version of the annotated August chart which documents all of the relevant twists and turns.

If you, like everyone else, are wondering what comes next, the first thing you'll want to watch in the new week is the yuan. China on Saturday "strongly objected" to Trump's Friday afternoon tariff hike, and the yuan was already on the back foot following the President's tweets.

You can expect the offshore yuan to test its all-time low of 7.14. The daily fix will be scrutinized for signs that Beijing is either trying to calm things down, or send another message Washington's way.

Obviously, any indication that Beijing is willing to let the currency absorb more of the tariff pressure would ostensibly be bearish for risk assets, but it's worth noting that last week brought the first ever revamped loan prime rate print (the "new" LPR), which marked the culmination of China's efforts to reform their two-track interest rate system.

Long story short, on the 20th of each month, China will publish the rate (there's a one-year tenor and five-year), which is set based on submissions from banks, which quote the new LPR in basis points on top of the medium-term lending facility ("MLF" for short). So, mathematically, cutting MLF rates will bring down LPR, all else equal. The point: Beijing may well cut open market operation rates soon thereby tipping a lower LPR in late September, and that option could substitute for weaker yuan fixes.

From a bigger picture perspective, what happened on Friday increases the odds that the Fed will ultimately cut rates to zero (or close).

As documented here, Jerome Powell's Jackson Hole speech was replete with references to the darkening global growth outlook and to geopolitical turmoil. On top of that, Powell alluded to the flatter Phillips curve, a nod to the purported safety of running the labor market (and the economy more generally) hot without risking a dangerous spike in inflation. The Fed chair also said, quote, "a lower r* combined with low inflation means that interest rates will run, on average, significantly closer to their effective lower bound." That's pretty explicit in terms of validating bets for a lower short-rate.

What you want to keep in mind here is that the longer the US economy holds up in the face of a deteriorating global backdrop, the bigger the risk of importing disinflation due to a persistently stronger dollar. I've talked about this in these pages before, but it's even more relevant after Friday.

One of the reasons the market is pricing in sharply lower rates in the US is arguably that some believe the Fed will have to cut aggressively even if there's not a recession, because if they don't, the imported disinflation from a strong dollar will eventually cause a downturn anyway. The whole thing has a certain deterministic feel to it, which President Trump seems to have picked up on.

The trade war is exacerbating the situation by imperiling the global growth outlook, thereby compelling foreign central banks to cut rates and lean ever more dovish. Meanwhile, the US economy is still hanging in there, having run out ahead in 2018 thanks in part to the tax cuts and fiscal stimulus. It's hard for the Fed to justify aggressive rate cuts when the US consumer is still spending, the labor market is still healthy and the jury is still out on whether the manufacturing sector is going to roll over in earnest or not. So, you're left with both an economic and a monetary policy divergence, with the former feeding into the latter and the trade war exacerbating both.

Clearly, the trade tensions have now worsened, which sets the stage for more lackluster data abroad, more accommodation from foreign central banks and, all else equal, a stronger dollar, which risks imported disinflation.

So, why did the dollar dip on Friday? Well, because President Trump's tweets were seen as materially raising the odds of outright, active FX intervention by Steve Mnuchin's Treasury. To be clear, Treasury doesn't have very much ammunition in that regard. The Exchange Stabilization Fund is small in absolute terms and tiny compared to the FX market. Here are the technical details of how Mnuchin can effectively marshal the entire $94 billion in the ESF (from a Barclays note):

While the ESF’s dollar holdings total only $22.6 billion, it has the ability to issue ‘SDR Certificates’ equal in value to its SDR allocations to the Federal Reserve in exchange for USD.

Additionally, it can ‘warehouse’ its euro and yen holdings with the Fed through an FX swap, but requires Fed FOMC authorization to do so. The outstanding FOMC authorization for warehousing currently stands at $5 billion, but in the past the FOMC has authorized as much as $20 billion. However, even assuming warehousing of all the ESF’s euro and yen assets, its $94.6 billion in total assets would represent just 2% of average daily FX transactions involving USD.

The Fed would be compelled to match that. In other words, the Fed, in keeping with historical precedent, would likely double Mnuchin's firepower to roughly $180 billion. Some on the FOMC would doubtlessly dissent against any such move. After all, there were two dissents last month on a 25 bps rate cut, so one can only imagine what the reaction would be if Powell came to his colleagues with a tacit mandate from Mnuchin to conjure up $90 billion for the purposes of helping the White House drive down the dollar. But, in theory anyway, Powell has unlimited ammunition. Here's Barclays one more time:

Were the FOMC fully on board with an effort to depress the exchange value of the dollar, because the Fed has the ability to create dollars by fiat, it could sell unlimited quantities. This would almost certainly require complete politicization of the Fed — a rising concern of market participants following the nominations of Stephen Moore and Herman Cain as Governors — but even then would not be the most likely outcome. As noted before, President Trump appears to see too-tight Fed policy as the primary source of excess USD strength, hence easing monetary policy would be a more straightforward action from a politicized Fed (and one that would attract less Congressional scrutiny).

The point in all of this isn't to suggest that unilateral intervention would be successful. It almost surely wouldn't. Historically, interventions were coordinated affairs, but nobody is going to coordinate with Trump in an effort to undercut their own exports by helping push down the dollar in the face of tariffs. Rather, the point is to say that on days like Friday when the President's pronouncements come across as particularly irritated and thereby foreboding, it stokes concerns about the volatility which would invariably accompany an intervention, and those concerns manifested themselves in the dollar falling against G-10 peers.

As alluded to in the latter passage from Barclays, the far more likely scenario when it comes to the dollar "problem" is that the Fed ultimately cuts rates to the effective lower bound.

Powell's speech provided a series of justifications for starting down that road, although clearly, President Trump did not read between the lines or bother trying to decipher the nuance.

Deutsche Bank's Stuart Sparks summed the situation up in a note out Friday afternoon. Here is a brief passage from the executive summary:

Powell enumerated slower global growth, trade policy uncertainty, and muted inflation as key risk factors for the policy formation process, noted the effects of a flat Phillips curve, and reiterated previous Fed comments that “a lower r* combined with low inflation means that interest rates will run, on average, significantly closer to their effective lower bound”. Taken together, these can be seen as validating market pricing for aggressive further Fed easing. China's announcement of additional tariffs on US imports, and President Trump’s response, have provided a catalyst for still more aggressive Fed pricing, and Powell’s statement can be seen as establishing the basis for an ultimate move to zero policy rates.

Assuming the dollar doesn't suddenly roll over and sustain a drop (unlikely barring an abrupt deterioration in the US economic data or concrete signs that Mnuchin is set to intervene), the Fed will find itself forced to cut rates further and faster, or risk a disinflationary FX shock that would further undermine the central bank's ability to fulfill its price mandate.

Of course, the Fed can wait and hope that the environment shifts. A sudden inflection for the better in the data abroad, a series of dour data points on the home front or, potentially, a lasting trade truce that helps stabilize the global growth outlook thereby removing some of the pressure for the FOMC's counterparts abroad to ease, could potentially take some of the pressure off when it comes to dollar strength.

But waiting around risks falling even further behind and having to catch up by rapidly cutting rates, something Deutsche's Sparks underscores in his exposition on the subject.

Ultimately, it's hard to see how the Fed doesn't end up back near zero one way or another.

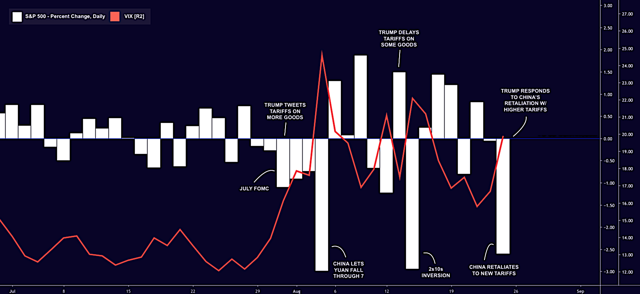

The worry is that all of this competitive easing (i.e., the "race to the bottom") will come to naught, as the tit-for-tat rate cuts and monetary accommodation offset each other in the FX space, while further distorting fixed income markets along the way, leaving everyone with negative rates and no ammunition to deploy in the event of another acute economic crisis.

And with that, I'll leave you with one final chart (this one from BofA) which shows that, to quote the bank, "a quarter of the world, in GDP terms, is now subject to negative central bank rates and a fifth of the world is now living with negative 10-year yields."

(BofA)

(BofA)

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario