Central Banks Are Spawning A Zombie Apocalypse

by: Cashflow Capitalist

Summary- A zombie company is one that regularly requires large capital infusions in order to survive, or one that is unable to generate enough cash to cover its fixed expenses.

- According to BofAML, 13% of companies in advanced economies are zombies, while 16% of American companies are zombified.

- Central bank monetary policy has been the primary cause of this rising tide of zombie firms. Ultra-low interest rates have allowed lousy companies to prolong their lifespan with cheap debt.

- This rise of zombie companies has some long-term negative effects on the economy.

A zombie apocalypse is silently spreading across America. Indeed, across the globe. One-eighth of the United States are zombies now.

Zombie companies, that is.

Source: Amazon.com

Source: Amazon.com

A zombie company is one that regularly requires large capital infusions in order to survive, or one that is unable to generate enough cash to cover its fixed expenses.

Your typical zombie company is heavily indebted and relentlessly wracking up more debt as it promises shareholders that financial soundness is on the way. The company may still be moving, but it is essentially dead or dying.

According to Bank of America Merrill Lynch, 13% of companies in the developed world are zombified (and 16% in the US), a number that has been rising in the previous decade despite the economic recovery. The number of zombie firms has only ever been higher (by about 15%) during the Great Recession.

A short spike in zombie companies during a recession is understandable, but how could there be a sustained rise in zombified firms during good economic times?

The answer, quite simply, is artificially and historically low interest rates. The Federal Reserve and other central banks across the world have pushed down interest rates and held them near zero over the past decade. In Europe and Japan, many rates are in negative territory. And this isn't even to mention the unprecedented expansion of central bank balance sheets.

Ultra-loose monetary policy across the world has spawned this zombie apocalypse in two ways:

First, by allowing companies to borrow cheaply and thus stay afloat longer than they would if rates were in a historically normal range; and second, by increasing the attractiveness of chasing returns in speculative assets over and against the ultra-low returns from government bonds.

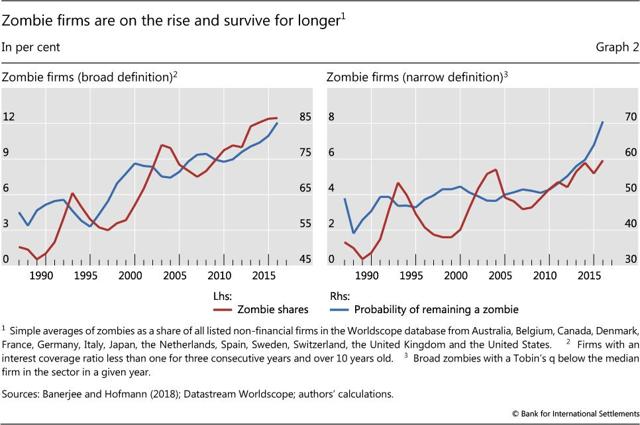

Since Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan first swooped in to backstop markets in the late 1980s with his famous "Greenspan Put," interest rates have gradually fallen as each successive Fed chairman followed in Greenspan's footsteps. Likewise, since the late 1980s, zombie firms have been on the rise:

Source: BIS Quarterly Review

Source: BIS Quarterly Review

Using a broad definition (the inability to cover interest expenses for three consecutive years), zombie firms have been rising from around 2% in 1990 to 13% today.

However, investors don't seem to care much. One need only look at the cousin of zombie companies, and that is the unprofitable IPO. Historically, these are somewhat rare, but they have grown exceedingly common in recent years.

In 2018, for instance, over 80% of initial public offerings were unprofitable, setting a new record for profitless IPOs. This year seems poised to produce as many or more unprofitable company IPOs, with Lyft (LYFT), Uber (UBER), Pinterest (NYSE:PINS) and others among them. Beyond Meat (BYND) has not yet seen a profit, and yet investors have demonstrated intense cravings for its cruelty-free shares so far.

Besides being the mark of late-cycle investor mania, demand for these profitless IPO shares signifies a paucity of safer yet still attractive investment opportunities out there. Ultra-low interest rates have helped push stock yields down and valuations up, which has in turn given a greater audience to speculative growth companies, including those that regularly post losses or can't cover their fixed expenses with net income.

Data on Japanese zombie companies signifies that zombified firms are mainly concentrated among small- and medium-sized enterprises, which likely also holds true in the United States and other developed countries. But zombie companies can certainly be larger, as in the case of a certain all-electric car manufacturer.

The Curious Case of Tesla

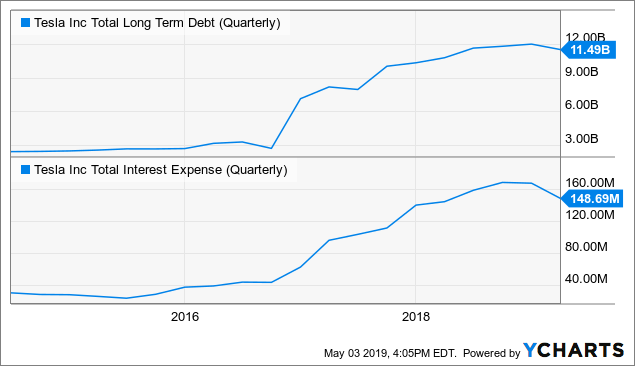

Tesla (TSLA) provides an interesting test case. Since 2014, the company has enjoyed only five profitable quarters out of nineteen. That means Tesla has reported profits for only ~25% of its existence as a public company. And yet, the company enjoys a very low cost of capital and has taken ample advantage of it.

GuruFocus puts Tesla's weighted average cost of capital (WACC) as low as 2.06%, and that is with a cost of debt of 5.95%.

With around $12 billion in debt, Tesla's debt-to-EBITDA sits at 7.05x, according to data from Seeking Alpha. And after burning through $1.5 billion in the first quarter of this year, the company recently announced plans to raise more capital — $650 million in new shares and $1.35 billion in new debt. This after a $702 million loss in Q1.

And yet, their new convertible debt will carry a coupon between 1.5% and 2%, and share prices would have to rise considerably to trigger a conversion.

In February of this year, Tesla secured $2 billion in new debt from the People's Bank of China to build a factory in Shanghai, the first round of which ($500 million) will be charged only 3.9% in interest.

Data by YCharts

Data by YCharts

The dip recently in debt and interest expense will prove fleeting, given the plans to raise more capital soon.

By the above definition, Tesla either is or comes close to being a zombie company. Regardless of one's view about the company as an innovator or investment, it's hard to deny that it has been kept afloat many profitless years through a combination of unusually low-cost debt and equity issuance.

Consequences of the Zombie Upsurge

Longer lifespans for zombified companies is not good for the economy.

The OECD lists three ways in which zombie companies drag down their respective economies (and, indirectly, the global economy):

- Crowding Out. The longer a zombie company survives, the longer it will soak up society's finite resources and prevent them from being used on more productive enterprises. "Zombies are less productive and may crowd out growth of more productive firms by locking resources (so-called 'congestion effects')," writes the Bank of International Settlements. "The estimates indicate that when the zombie share in an economy increases by 1%, productivity growth declines by around 0.3 percentage points."

- Capital Misallocation. Not only do zombie companies crowd out healthy companies, they also do plenty of wasteful spending themselves. One study of Chinese manufacturing companies demonstrates that zombie firms promote overcapacity — when an industry has the capacity to produce much more than existing demand could satisfy. Many zombies either produce more or build out the capacity to produce more in an attempt to turn a profit, even if the market is not calling for increased production.

- Delayed Technological Diffusion. A consequence of zombie companies' tendency to misallocate capital and crowd out more productive companies is a gradual fall in investment and innovation.

HSBC senior economist Stephen King echoes the above line of reasoning that these negative outcomes are a result of ultra-loose monetary policy over the previous decade. The higher asset prices spurred by excessive easing masked company issues and prevented the need for cost-cutting.

"Capital markets were thus no longer able easily to perform their central function, namely the efficient allocation of capital. Too much capital stayed in bloated and inefficient companies leaving too little to support the growth of smaller, more dynamic, enterprises."

This goes a long way in explaining why productivity growth has been slowing since the 1980s and especially since the Great Recession. It also helps to explain the lack of a strong rebound in domestic investment after the recession.

King's proposed solution to the problem is simple: "Let already-dead — or 'zombie' — companies collapse."

The OECD concurs, saying, "Reforms that accelerate corporate restructuring can have powerful effects on productivity." It turns out that creative destruction is hampered when the "destruction" part is diminished, but it can be rejuvenated by letting the whole process work.

One way to do this (probably the most straightforward way) is to normalize interest rates to a historically average range, come what may in the financial markets. This would undoubtedly cause significant short-term pain in terms of layoffs and wealth destruction, but these are preferable to the long-term pain of a permanent damper on growth and productivity.

In lieu of such reforms, it appears the rising tide of zombie firms will contribute further to the low-growth, low-inflation, low-rates future we are likely to see, which I've written about elsewhere.

"Apocalypse" may not be the right word for what central banks are spawning. But what they are spawning is perhaps just as scary.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario