by: The Heisenberg

Summary

- This post is equal parts critique (of the over-democratization of markets), recap (of the bond rally and its reversal) and in-depth analysis (of the mechanics behind recent action).

- The late-March rally in bonds is poorly understood. It was, at least in part, another example of a "false optic".

- Misinterpretation helped fuel last month's "growth scare" narrative.

- And in a testament to how untrustworthy narratives can be, last month's "growth scare" story gave way to this month's "cyclical reflation" tale in the blink of an eye.

- The late-March rally in bonds is poorly understood. It was, at least in part, another example of a "false optic".

- Misinterpretation helped fuel last month's "growth scare" narrative.

- And in a testament to how untrustworthy narratives can be, last month's "growth scare" story gave way to this month's "cyclical reflation" tale in the blink of an eye.

Most people familiar with my musings are aware that I harbor grave reservations about the over-democratization of markets.

Plain vanilla index funds that offer investors low-cost, broad-based exposure to benchmark equity indexes are obviously a great thing and balanced funds which pair that exposure with a simple allocation to bonds are even better. They should be the building blocks of any portfolio.

That assessment is more truism than opinion, which is why I long ago ceased responding to anyone who challenged my critiques of democratized markets by extolling the virtues of S&P 500 index funds.

It's never been clear to me, though, why we need a plethora of ETFs that allow retail investors to trade in and out of markets in the blink of an eye and it's even less clear to me why we need ETFs that encourage non-professional investors to day trade things like high yield credit, leveraged loans and emerging market assets.

Before anyone tunes out, let me quickly steer this discussion off the rumble strips and back onto the highway. This isn't a post about liquidity mismatches in credit ETFs or about why I think the epochal active-to-passive shift is pernicious (those two topics are near and dear to me, but they tend to elicit eye-rolls from some readers).

Rather, this is a post designed to make a simple point about the extent to which the over-democratization of markets sets the stage for widespread misinterpretation which can then translate into manifestly false narratives and, ultimately, undesirable outcomes.

I made a similar point in one of the few posts I've written for this platform in 2019 called "Fata Morgana". There, I described how, in Q4, investors suffered from a kind of parallax effect - a confused perspective. In late November, hedging dynamics and the unwind of someone's long WTI/short Nat Gas spread trade accelerated crude's collapse, leading some to believe that oil, which was already plunging, was signaling something particularly dire about the global economy. Shortly thereafter, misunderstandings with regard to the Fed's efforts to normalize policy and misplaced angst about inversions, sparked a panic. Stocks dove, spreads widened and the volatility-liquidity-flows feedback loop kicked in. At the same time, incessant media coverage, tweets from the president and an extremely engaged investor base (from a public interest perspective) perpetuated the spiral.

Some of that, I would argue, stems directly from too much engagement by non-professional investors and (far) too much media coverage which, even when largely accurate and done responsibly, risks lapsing into hyperbole or otherwise pouring gas on the proverbial fire.

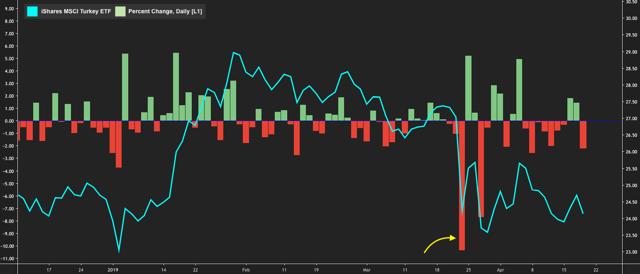

Before I bring you the latest example of a market Fata Morgana, allow me to use a (very) recent example to make a point about the over-democratization of markets. On Thursday, the iShares MSCI Turkey ETF (TUR) had its seventh-worst day of 2019, falling more than 2%. To be clear, it's not unusual for that product to fall more than 2% in a single session - there were dozens of such days last year when Turkish assets were besieged by a combination of external and idiosyncratic factors which, by August, conspired to push the lira to the edge of crisis. Additionally, it should be noted that Turkish stocks have had a rough go of it lately. Local elections held late last month stoked uncertainty and, ultimately, the Borsa Istanbul wiped out most of its YTD gains.

That latter bit (about the municipal vote) strikes at the heart of the issue. Clearly, some large investors who use TUR to gain exposure to Turkish equities know what they're doing and as such, are well apprised of local dynamics. But I don't think it would be a stretch to suggest that most "average" (and I don't mean that in a pejorative way) investors who own TUR are largely in the dark about what moves Turkish assets on any given day. And that's to say nothing of the vagaries of Turkish politics, which themselves are inextricably bound up with the fate of the country's markets.

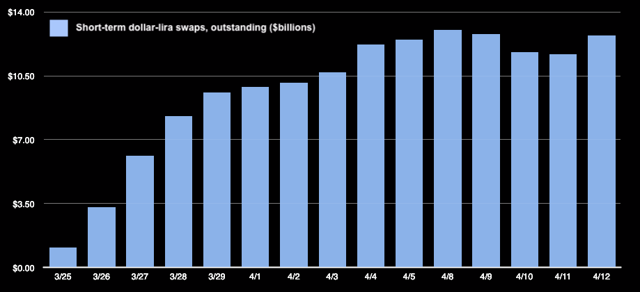

For instance, Thursday's decline in Turkish equities was, for the most part, the result of questions about the country's foreign reserves. Without getting too far into the weeds on this, the Financial Times decided to take a look at the central bank's swaps book and this is what they found:

Why is that a problem? Well, the central bank's borrowings from banks (i.e., those swaps) never rose above $500 million - with an "m" - from January through the end of March. You'll note that the numbers in the chart are in billions - with a "b". The implication is that Turkey is now working pretty hard to inflate its reserves.

Again, the point isn't to get mired in this particular discussion (if you want to, there's more here), but you should also note that one of the worst days in years for TUR came on March 22 (yellow arrow below) when traders couldn't explain a sudden decline in the country's reserve pile.

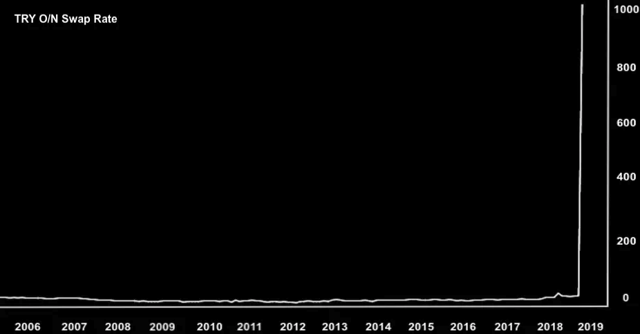

That selloff coincided with a dastardly day for the currency which, in turn, led to a vicious crackdown the following week, when President Erdogan essentially trapped investors in the lira in a bid to keep the currency stable ahead of the above-mentioned local elections. On March 27, the overnight rate surged above 1,000%.

Ok, so, who cares? Well, anyone who owns TUR, presumably, and that's a problem because it's not entirely clear to me why anyone save emerging market fund managers and seasoned FX traders should have to worry about any of the above. In fact, it is wholly unrealistic to expect "average" investors to sort through what I just outlined, which raises the following simple question: Do we really need a product that allows anybody and everybody to day trade Turkish equities? If such a product (i.e., an ETF from a top-tier sponsor like iShares) is in fact desirable, then shouldn't it be the purview of institutional investors and, perhaps, active EM fund managers who can use it to hedge?

While I don't know the answers to those questions definitively, what I do know is that, anecdotally anyway, it stands to reason that the more democratized the market gets, and the more of these vehicles there are, the easier it is more investors who have no business actively trading certain assets to do just that. The result, I would argue, is a less efficient market as uninformed investors attempt to decipher things they shouldn't have to decode.

It's relatively easy to make that case when it comes to something like Turkish stocks. Given the myriad idiosyncratic factors involved, suggesting it's preferable to leave the decision making to active EM fund managers (or, if you like, to say investors wanting passive exposure should opt for a broader-based EM ETF so as to mitigate the perils associated with any one country) is not a particularly contentious thing to say.

What is contentious, though, is to suggest that most investors probably shouldn't be in the business of trading macro themes with ETFs at all, even when the themes relate to subjects most engaged investors claim to know something about and even when the ETFs and the underlying assets are extraordinarily liquid.

Enter another Fata Morgana.

Late last month, developed market bond yields dove following the March Fed meeting when, against all odds, Jerome Powell and co. managed to deliver yet another "dovish surprise". I say "against all odds" because, generally speaking, the view on the street was that the Fed couldn't possibly get any more dovish without actually cutting rates.

Two days after the Fed meeting (so, on Friday, March 22) data showed Germany's manufacturing slump deepened in March. The new orders subindex (on the March PMI) fell to 40.1, the lowest since 2009. 10-year German yields pushed below zero for the first time since 2016. The mood, as I put it that morning, was "doom and gloom".

Two days previous, Jerome Powell managed to do what Mario Draghi couldn't earlier in the month:

Deliver a dovish surprise without accidentally "confirming" the market's worst fears about the outlook for growth. One of my favorite analyst quotes of 2019 comes from BofAML's US credit strategist Hans Mikkelsen who, following the March Fed meeting, wrote the following:

Just when you thought the Fed could not possibly deliver another dovish surprise, they did. Of course communicating dovishness is always tricky as there is a delicate balance between the benefit of stimulus and the underlying driver, which is economic weakness.

Mikkelsen probably didn't mean to say anything particularly novel there, and indeed he didn't. The beauty of that passage lies not in profundity, but rather in how concisely Mikkelsen communicates what is perhaps the key quandary of monetary policy in the post-crisis world. There is a fine line between assuaging market fears about the outlook for the economy by indicating policy will be accommodative, and accidentally spooking markets further in the course of justifying a dovish lean.

In a rare misstep, Draghi went too far in March, when the ECB delivered a cut to the euro-area growth outlook dramatic enough to override the good vibes that would have "naturally" accompanied a renewed commitment to accommodation.

Powell, on the other hand, largely succeeded. The March Fed meeting was overtly dovish, but risk assets were not truly spooked. Or at least not until 48 hours later, when the above-mentioned "doom and gloom" narrative took hold. In response to a friend's question about whether the March 22 selloff was an opportunity to buy the proverbial dip, I wrote something called "As Bonds Find ‘Best Friends’, Stocks Grapple With Inversion Freakout", in which I detailed the series of events that helped spark the second-worst day for US stocks of the year after the US 3M-10Y curve inverted.

Here are some quick excerpts:

JGB yields had to play catch up (or, actually, “catch down” is better) to the dovish Fed after a holiday and the Japan CPI miss threw gas on the fire. Then came the grievous German manufacturing data and it didn’t help that France’s composite PMI sank back into contraction territory. Ultimately, the die was cast by the time the US session got going.

The data from overseas underscored growth concerns and, more importantly, appeared to lend credence to the idea that the Fed’s dovish surprise might have been predicated on the FOMC “knowing something” everyone else doesn’t know.

At that point, the "growth scare" narrative became somewhat entrenched. Predictably, the media and every armchair macro watcher on the planet, rushed to breathlessly opine on i) the US curve inversion, ii) what a return to sub-zero bund yields in Germany was "saying" about the world's fourth-largest economy and iii) what might happen in the event forthcoming activity data out of China were to disappoint.

To be clear, some of that breathless commentary was justified. Growth worries were proliferating and for good reason. 2019 has been a year defined by ominous signs and warnings about the global economy and, after all, there's a reason why central banks felt the need to pivot so sharply.

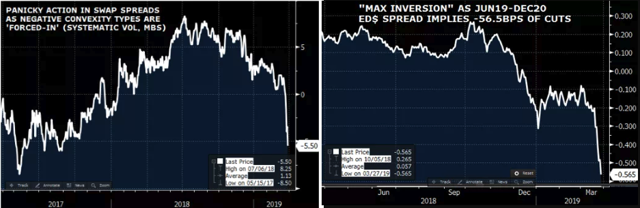

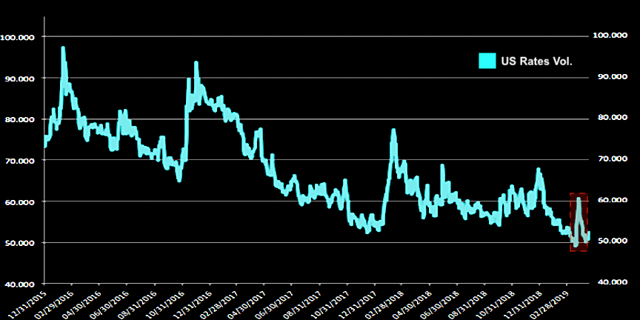

The problem, though, is that most casual observers were oblivious to the fact that what was going on in US rates wasn't entirely attributable to a "growth scare". Previously moribund rates volatility suddenly woke up during the week of March 25, and by Wednesday of that week, things were getting really interesting to the detriment of risk asset sentiment.

"Global rates [are] again foaming at the mouth with another leg of panicky grab, while conversely [we] see risk assets spooked by the instability seen in the rates-trade", Nomura's Charlie McElligott wrote early on the morning of March 27, adding that the following color:

UST- / swap spread- / front-end- / front-end flattener- 'stop-ins' again 'going off' overnight, with likely exacerbation culprits again being negative convexity types from MBS and systematic short vol strategies.

That may sound like gibberish to most investors, and indeed, that's the point. What the vast majority of casual market observers were interpreting as a "growth scare", was at least partially the product of convexity flows and hedging following the March Fed.

As noted above, rates volatility suddenly jumped after grinding to record lows earlier in the year.

"This spike in rates vol. is making headlines all over the place today", I remarked, in an e-mail to a friend on March 26. "I guess you've seen that - Bloomberg is running headlines like 'calm goes the way of the dodo'."

"It is very simple", this person responded, adding the following:

Clients were short gamma when rates weren’t moving. The street was long gamma, of course. Since last week, rates have moved a lot, so some of those strangles yield enhancers sold are at the money—they became shorter gamma and started covering. In the meantime, the street became less long, so vol. had to go up.

The next day, Bloomberg ran a feature story called "Here's Why U.S. Bond Yields Plunged So Much Over the Past Week". It contained the following layman's explanation:

Treasuries rallied after the Fed signaled it was done raising interest rates for the moment, driving yields on 10-year notes down to levels last seen in 2017. That forced two sets of traders -- those who had bought mortgage bonds and those who had bet markets would remain calm -- to turn to derivatives markets to tweak their portfolios or stanch their losses. They snapped up positions in interest-rate swaps, pushing Treasury yields down even more.

On March 29, Deutsche Bank's Aleksandar Kocic delivered a characteristically trenchant take on the whole episode, complete with a "seesaw" analogy to illustrate the difference between the way things used to be (when MBS hedging was the dominant market mode) and the way things are now (what he calls the "insurance mode", defined by periods of placidity shattered by episodic vol. spikes). For those interested, I did a lengthy post on that at the time, called "The Gamma See-Saw: Deutsche’s Kocic Explains This Week’s Biggest Market Story".

All of that served to exaggerate moves in US rates and those exaggerated moves were misunderstood and generally misinterpreted by most market participants who assumed that the ferocity of the rally in bonds late last month was solely a function of growth worries. That misinterpretation led many to fearfully point to what's colloquially known as "the jaws" or, more simply, the yawning gap that developed on a simple chart of the S&P (which continued to grind higher) and 10-year yields (which hit their lowest levels since December of 2017 late last month). Here's what the "jaws" looked like on March 30:

"It really depends from which direction the jaws close – through higher rates or via lower equity prices", one client told Goldman a few weeks back.

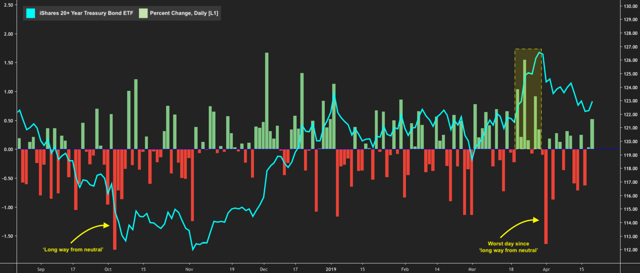

So, many investors went into April believing the bond market was "saying" something more than it was actually "saying" about growth. Had you not appreciated the role played by convexity flows and hedging dynamics, you might well have gone into the first week of April not realizing that with positions mostly squared and two critical data points on deck (March PMIs from China and US payrolls), the stage was set for a pretty violent snapback in, for instance, the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) which had its worst single session decline since "long way from neutral" on April 1. Have a look at this chart:

In that yellow-shaded box is the bond rally that played out following the March Fed. On April 1, China reported better-than-expected PMI data, eliciting a huge sigh of relief from those concerned about global growth. With the impact of hedging flows on US rates in the rearview, things reversed in dramatic fashion, leading directly to the selloff in TLT denoted with the yellow arrow and caption in the visual above. A subsequent beat on ISM in the US lent further credence to the idea that the March growth scare was perhaps overdone. On April 3, Nomura's McElligott summed up the situation as follows:

Currently this is simply about the re-pricing of growth expectations which, to me, is partially due to the potentially ‘false optic’ created by the enormity of the convexity hedging impact on Rates over the past two weeks into the rally having caused an ‘overshoot’ of the growth-scare narrative.

There you go - another "false optic". Another confused perspective. More financial parallax.

Another Fata Morgana.

In the three-ish weeks since, the market was pleasantly surprised by, in order, a solid March jobs report in the US (helping to erase the memory of February's debacle), a better-than-expected read on exports out of China, across-the-board beats on Chinese credit growth and, on Wednesday, a blowout set of numbers from Beijing which showed GDP stabilizing in Q1, while retail sales and industrial production surprised markedly to the upside.

The end result: "The jaws" have closed in the "right" direction, with 10-year yields rising some 16bps in April (top pane in the visual). Meanwhile, German bund yields are back in positive territory despite still-dour manufacturing data and Berlin slashing its official outlook for growth to just 0.5% in 2019 (the yellow circle in the bottom panel shows that in March, German bund yields converged with yields on 10-year JGBs, underscoring the "Japanification" story in Europe).

(Heisenberg)

So, what did we learn from all of this? Some readers will invariably say "nothing", but that would be wholly disingenuous. For one thing, anyone who made it through this piece now knows more than they did previously about at least something, whether it's what's going on in Turkey or what accelerated last month's much ballyhooed bond rally.

More importantly, what the above underscores is that in today's markets, over-engagement by average investors (and "average" isn't meant as a comment on ability, but rather to denote anyone for whom investing isn't a profession) and the deafening cacophony of the financial media/blogosphere makes it all too easy for misleading narratives to take the reins. Once that happens, narratives are notoriously stubborn when it comes to ceding control of the carriage, irrespective of evidence. Ask any casual observer of markets what was behind the late-March bond rally and they'll tell you it was a "growth scare". As explained above, they'd be only partially correct.

A more nuanced argument could well be that because growth concerns prompted the Fed to deliver another dovish surprise and because that dovishness was behind the initial moves which kicked off all the manic hedging activity, "growth scare" was in fact the proximate cause of the bond rally. I'd concede that.

But, in general, my contention is that we'd all be better off if we didn't have a setup where every mom and pop investor on the planet is free to day trade macro themes with ETFs based on a never-ending stream of real-time, broad-strokes commentary pushed out at warp speed by journalists and bloggers all parroting the same theme du jour in a kind of "publish first, ask questions later" fashion. The late November collapse in oil prices (mentioned above) was easily explainable by reference to producer hedges and some soured spread trades. The 2s5s and 3s5s inversions in December begged for nuance, but all anyone cared about was cramming "inversion" into headlines. The ferocity of the late-March bond rally was in part down to convexity flows following the Fed, but it was far easier to churn out dozens of "growth scare" stories first and then call the street's rates desks five days later to see if there was more to the story.

As should be clear from the excerpted conversation I had with a friend on the street last month, there are often "quite simple" explanations for large moves and the people manning the desks are more than happy to elaborate if anyone cares to ask. But that takes effort on the part of the media (to write) and on the part of market participants (to understand). It's far easier to cram a given move into a cookie-cutter narrative.

These narratives have a tendency to become self-fulfilling as we saw in December. Once things get moving in one direction, systematic strategies get roped in, headline-scanning algos are triggered and before long, the nuance becomes irrelevant. Fortunately, the string of upbeat data surprises mentioned above served to short-circuit the "growth scare" story and now, were trading squarely on a "nascent cyclical reflation" theme.

Going forward, that theme will live and die by the prevalence (or not) of more "green shoots".

With central banks now firmly committed to a dovish policy stance, good data can arguably be interpreted as just that - good data. The "good news is bad news because it suggests further stimulus and accommodation isn't necessary" story popped up again vis-à-vis the recent run of positive data out of China, but as far as developed market central banks go, the bar for putting rate hikes and/or normalization back on the table is impossibly high.

In other words, barring a series of "rogue" inflation prints, DM policymakers will be sitting on their hands for the foreseeable future, so we needn't fear good news on the worry it will tempt central banks to lean hawkish again.

That should be a volatility suppressant and, assuming the data hangs in there, we may soon be able to drop the "nascent" adjective from the "nascent reflation" headlines.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario