A multidecade rise in profit margins may already be in the process of reversing, taking the wind out of the stock market’s sails for years to come

By Justin Lahart

Illustration: Mikel Jaso

It isn’t how much you make but how much you keep.

Most investors grasp that concept when it comes to their own finances, but they also need to consider how it applies to the companies they own. A long-term tailwind to stocks from expanding profit margins is at risk of flipping into reverse.

Steady increases in margins have been the stock market’s secret sauce since the 1980s, allowing earnings to grow at a much faster clip than sales and pushing share prices higher as a result. If profit margins were merely to return to their levels of 20 years ago, then earnings—and share prices—might be 40% lower than they are today.

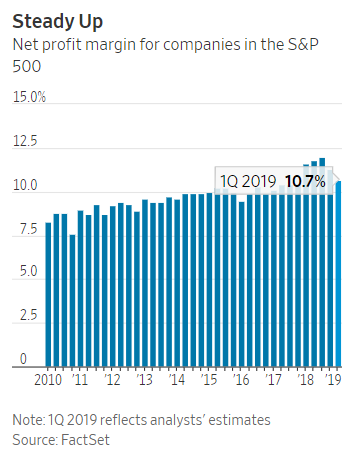

For the first time in over two years, corporate profit margins are falling. In a shifting economic and political environment, this may be only the beginning of a long slide. The S&P 500’s forecast first-quarter profit margin—or earnings as a share of sales—is 10.7%, according to FactSet. While down nearly a percentage point from a year earlier, that would, with the exception of 2018, still count as a record high.

The decadeslong increase in profit margins was the result of many things going right at once, including a steady decline in labor costs, increases in global trade, lower taxes and gains in market share. Unfortunately for companies, each one of these trends seems at risk to at least partially reverse itself in the years ahead.

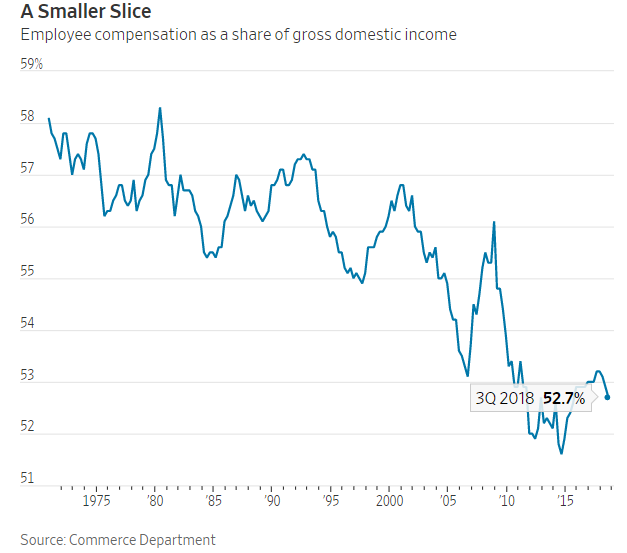

Start with labor costs. One way to consider these is to look at the income earned by U.S. workers as a share of gross domestic income—a sum of all wages, profits and taxes the economy. This has been falling for decades, dropping to about 53% in the first three quarters of last year from about 58% in 1980 according to the Commerce Department. Among the reasons for this downtrend: a diminution of employees’ bargaining power as union membership declined and an expansion of global trade that allowed companies to shift production to countries where labor costs are cheaper—particularly China.

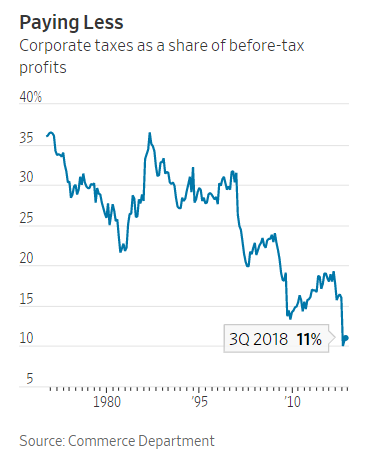

Next, taxes. Last year’s tax cut was just the most recent in a series of actions that have dramatically lowered companies’ tax bill. Taxes came to about 11% of before-tax U.S. corporate profits in the first three quarters of last year, according to the Commerce Department. In 2000, the tax share was about 32%. Additionally, U.S. multinationals appear to have steadily shifted more of their domestic profits to tax havens such as the Cayman Islands since the 1990s, effectively reducing their tax rates by even more than the Commerce Department data show.

Big companies, like those in the S&P 500, also have gained market share. This hasn’t only given them a larger share of the profit pie, but it’s also allowed them to reduce costs through greater scale. It also has reduced competition for labor, some economists argue, adding to big companies’ power to set wages. As of 2016—the most recent year with available data—about 47% of U.S. workers were employed at firms with 1,000 or more employees. That compared with about 42% in 1996.

But all of these trends—the reduction in labor’s share of the economy, the decline in corporate taxes and big companies’ amassing of increased market share—seem unlikely to persist.

Worries about inequality are on the rise and, with Democrats vying for their party’s 2020 presidential nomination viewing it as a hot-button issue, proposals to combat it through higher taxes and other redistributive policies are gathering momentum. Meanwhile, the U.S. trade fight with China and the fact that Chinese wages have steadily risen may give U.S. multinationals second thoughts about shifting more production abroad.

Criticism of large companies’ power has risen, too. As part of his beef with Amazon.com Chief Executive Jeff Bezos, President Donald Trump has argued that the giant internet retailer’s business practices are unfair. Massachusetts senator and presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren earlier this month proposed breaking up Google, Amazon.com and Facebook .

At the very least, this is an environment in which companies will struggle to squeeze out much more from these favorable trends. It seems unlikely workers’ income share will continue to decline. Corporate taxes probably aren’t heading even lower. The forces of globalization that helped bolster earnings are on the wane. Profits will come under pressure if companies can’t enjoy the marginal benefits of these trends.

Climbing margins have given investors a sweet ride. The downhill portion could be bumpy and highly unpleasant.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario