Beware the Fed’s Feedback Loop in Emerging Markets

Many countries’ economies look healthier because of volatile investment flows, not real economic progress

By Jon Sindreu

The Federal Reserve’s shift away from raising interest rates has once again driven investors toward juicy returns in emerging markets. They need to be careful of a dangerous feedback loop: The very fact that money flows into these countries makes them look safer.

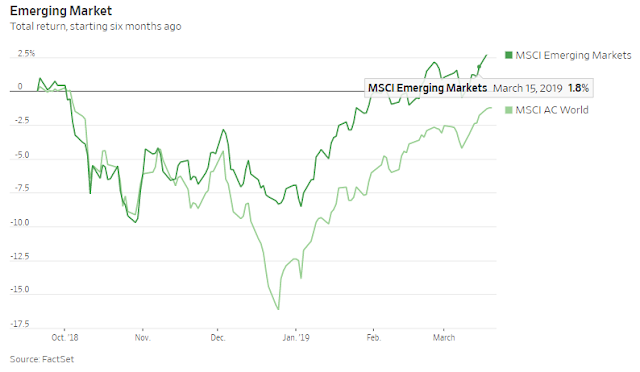

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell doubled down Wednesday on his new wait-and-see approach to monetary policy. This will prolong the good times for emerging markets, where stock markets have returned 2.8% over the past six months, compared with a 1.2% loss for all stocks globally, according to the respective MSCI indexes. Currencies in countries with high rates have also rallied more, pointing to speculative yield hunting.

Developing economies are looking impressively resilient, especially considering worries about a China-led global slowdown. Earnings expectations have stabilized and investors seem to have decided that the sharp selloff in emerging-market assets last summer had more to do with isolated problems in Turkey and Argentina than broader concerns.

A welder at a factory in Nantong, China. Photo: str/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

The problem is that investors’ confidence could be creating a deceptive sense of calm. This will suddenly reverse if the dollar appreciates or cash flows out.

Two papers recently released by the Basel-based Bank for International Settlements highlight new evidence of this effect. First, by looking at a database of nonfinancial firms in Mexico, the BIS found that corporations tend to do the same as international investors when the U.S. dollar is weak: They borrow in greenbacks at low rates to lend in pesos at higher yields, and pocket the difference.

Their aim isn’t usually to speculate, but to extend trade credit to partners with less access to global capital. Still, the need to preserve these business relationships means that, when the dollar strengthens again, companies tend to offset losses by slashing investment rather than closing the credit taps, researchers found. This means that bouts of currency volatility—like last summer’s—likely damage these countries’ long-term productivity growth.

The research flies in the face of the economic-textbook idea that weaker currencies improve poorer countries’ chances because their exports get cheaper.

A second piece of BIS research, released this week, found that sovereign-debt investors in emerging markets tend to demand less compensation when the dollar is weak, even when buying bonds in local currency.

This is shortsighted: A weak dollar boosts credit to emerging markets, making them look stronger than they are. Investors often don’t give enough weight to this, mistakenly attributing both economic improvements and crises to local political developments rather than the ebb and flow of global capital.

Right now, investors are happy to clip their coupons, lulled by the Fed’s dovish mood music.

But they should be less blasé about the risks of a weaker-than-expected global economy and the return of a stronger dollar.

George Soros famously dubbed “reflexivity” the phenomenon whereby markets are subject to feedback loops between sentiment and reality. Volatile exchange rates make emerging markets particularly extreme examples.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario