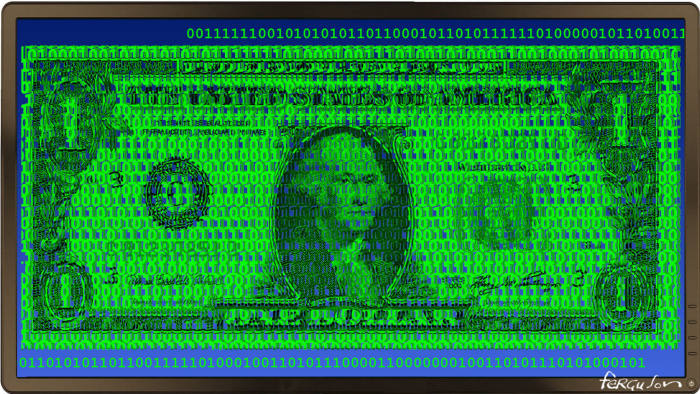

The libertarian fantasies of cryptocurrencies

Digital money needs tough regulation rather than bleating in favour of ‘innovation’

Martin Wolf

“Move fast and break things” was the famous motto of Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s founder. Among those broken things have been norms of trustworthiness essential to democracy. An activity as dependent on trust as democratic politics is money and finance. This is why developments here cannot be left to the greed and fanaticism we see in the world of cryptocurrencies. Careful assessment needs to be made of this world and its relationship to the broader one of digital money. Change is indeed on the way. But it cannot be left to happen.

The cryptocurrency movement would reject that, because its roots lie in anarchistic libertarianism, as Nouriel Roubini of New York University argues. This ideology also beats in the hearts of many Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. They are not altogether wrong: the state can be a dangerous monster. But it is also essential: it is humanity’s ultimate insurance mechanism.

The world of anarchy is one of competing bandits. It is far better to have just one, as the late Mancur Olson argued in Power and Prosperity. Moreover, he added, liberal democracy helps tame that bandit. States exist to provide essential public goods. Money is a public good par excellence. That is why dispensing with the role of governments in money is a fantasy. The history of the so-called cryptocurrencies demonstrates this.

Money is a store of value, a unit of account and a medium of exchange. To be a really good currency, it needs to be durable, portable, divisible, uniform, limited in supply and acceptable.

How do cryptocurrencies measure up against these requirements? They are clearly neither a store of value nor a good unit of account, as their vast swings in price show. They are not a good medium of exchange, because law-abiding people and businesses do not want to own assets that are, by virtue of their anonymity, ideal for criminals, terrorists and money launderers. While an individual cryptocurrency can be limited in supply, the aggregate supply is infinite; according to the International Monetary Fund: “As of April 2018, there were more than 1,500 cryptocurrencies.” There could just as easily be 1.5m.

The best way to view cryptocurrencies is as speculative tokens of no intrinsic value. One could have value if it became the currency of choice of a jurisdiction. Yet there is a compelling reason why, in normal circumstances, people use the currency of their own government: they need to pay taxes. To do that, they need to render money the government accepts — principally, deposits denominated in national currency at banks with accounts at the central bank. This, in turn, is the government’s bank. The state can enforce this: that is why it is the state. You may have an online existence. But you also have a physical body, which the government can put in prison if you don’t pay your taxes. This is why the state can enforce its domestic monetary monopoly. Only those operating in the shadows would seek to operate outside this framework — and even they will find it very dangerous.

As the Financial Times’ Izabella Kaminska and Martin Walker of the Center for Evidence-Based Management argued in evidence for the House of Commons Treasury committee, so far the cryptocurrency craze has made online criminality easier, created bubbles, fleeced naive investors, imposed grotesque waste in so-called “mining”, offered funding for malfeasance and facilitated tax evasion. What is the social value in any of this? There is no good case for new anonymous currencies. Cryptocurrencies are not yet important. But they need tough regulation. It is no longer enough to bleat in favour of “innovation” or “freedom”.

Whatever the dangers of cryptocurrencies may be, “distributed ledger technology” including “blockchain” might prove valuable in making activities dependent on safe record-keeping, notably finance, more efficient and secure. A huge number of experiments is under way. A recent Geneva Report on the Impact of Blockchain Technology on Finance, argues that such technology can “mitigate the ‘cost of trust’” and so “lower overall costs, reduce economic rents and create a more secure and fairer financial system”. That would be welcome, if true. Let us experiment. But all the important public policy requirements of transparency and financial stability must continue to apply.

One of the most important potential innovations in the broad area of digital money is potentially the opposite of cryptocurrency: central bank digital money, perhaps as a substitute for cash and possibly as something more radical than that. Analysis at the IMF and the Bank of England demonstrates that we need to be clear about what central bank digital money is to achieve, how it relates to cash or bank deposits, and whether it could be a substitute for central bank reserves, which at present can only be owned by commercial banks.

Replacing cash with digital tokens of some kind would be relatively simple. It would mainly raise questions about the degree of anonymity of such replacements. Far more potentially revolutionary and destabilising possibilities would arise if the public at large were able to switch from deposits at commercial banks to absolutely safe accounts at the central bank. This radical idea has obvious attractions since it would remove the privileged access of one class of businesses, banks, to the monetary services of the state’s bank. But it would also transform (and surely destabilise) today’s monetary system, in which the state seeks to guarantee and regulate a money supply largely created by private banks and backed by private debts. Yet the revolutionary fact is that it would now be easy for everybody to hold an account at the central bank. Technology is eliminating the historic difficulties over such access.

As everywhere else, innovation is transforming monetary possibilities. But not all changes are for the better. Some seem clearly for the worse. The right way forward is to reject libertarian fantasy, but not change itself: our monetary system is far too defective for that. We should adapt. But, history reminds us, we must do so carefully.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario