Doubting The Gods

by: The Heisenberg

Summary

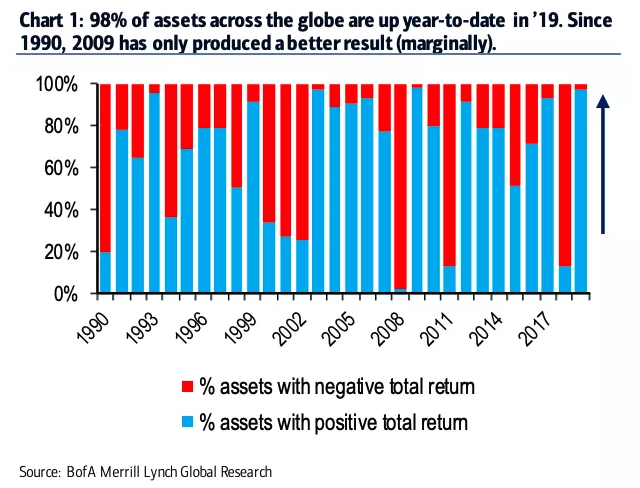

- 98% of global assets have posted a positive total return YTD.

- But suddenly, price action looks uninspiring again.

- A lackluster week even as the central bank "pivot" went global suggests market participants doubt monetary policy has the capacity to fully offset key tail risks.

- But suddenly, price action looks uninspiring again.

- A lackluster week even as the central bank "pivot" went global suggests market participants doubt monetary policy has the capacity to fully offset key tail risks.

- Equities traded uninspired last week, and that should come as no surprise.

As Deutsche Bank's Aleksandar Kocic put it on Friday evening, "there is a sense of fragile local stability", and that fragility is directly attributable to a lack of visibility around virtually all of the key risks for markets.

News that President Trump will not meet Xi Jinping ahead of the March deadline beyond which tariffs on $200 billion in Chinese goods will more than double (to 25%) derailed sentiment materially on Thursday. While Steve Mnuchin and Bob Lighthizer will travel to Beijing next week to resume trade talks, we've all seen this movie before. Structural sticking points (e.g., IP theft and forced technology transfer) appear intractable and the threat of an executive order banning Chinese telecom equipment from U.S. wireless networks is a stark reminder that the Huawei soap opera is far from over.

Meanwhile, the global recession narrative continues to gather adherents. The economic downturn story never really went away despite the sharp snapback in risk assets to start the year. It's just one body blow after another, with the latest hit coming from The European Commission, which on Thursday cut its growth forecasts for all of the euro-area’s major economies. Italy is of course already in a recession and Germany looks like it might be next.

Finally, the drama inside the Beltway picked up considerably this week as House Intelligence Chairman Adam Schiff moved aggressively forward with a reinvigorated probe into election interference and House Democrats grilled Acting Attorney General Matt Whitaker in a highly contentious hearing on Friday. As a reminder, the more fraught that situation becomes, the higher the likelihood that the debt ceiling will end up getting used as a bargaining chip over the next couple of months. Markets will not be amused if politicians start playing around with America's credit rating (again), especially not at a time when the U.S. is issuing mountains of debt and the nation's biggest creditor ((China)) has pared its holdings for six consecutive months (through November).

Although I went out of my way in December to pound the table on the idea that stocks had overshot economic fundamentals and that a bounce was likely in the cards, part of the rationale for that thesis (as delivered in dozens upon dozens of posts over on my site) was that i) the looming government shutdown didn't yet threaten to spillover into the debt ceiling debate and ii) the 90-day trade truce had just started, meaning it would be at least two months before people would be inclined to sell on every ostensibly negative trade headline again.

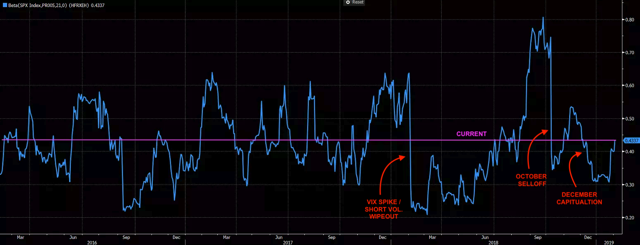

At the same time, positioning had undergone a veritable purge, with the Long/Short universe having de-netted/de-grossed materially following the October rout and the systematic crowd still largely sidelined as well. In other words, there was nobody left to sell, especially after mutual fund investors bailed en masse midway through December. The top pane below proxies for the Long/Short crowd's exposure using a moving beta of the HFRX Equity Hedge index to the S&P while the bottom pane is a proxy for vol.-targeting strat exposure.

(Bloomberg)

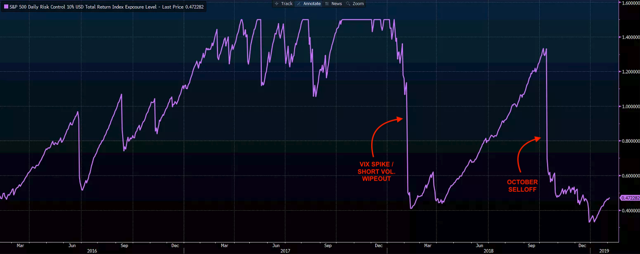

Around the same time, the S&P's (SPY) traditional beta to the short rate had been restored (see chart below) thanks to the selloff, meaning the Fed had largely succeeded in restriking its "put" and would likely be inclined to step in with something overtly dovish to ensure financial conditions didn't tighten so much that it jeopardized the committee's ability to engineer a "soft landing."

(Deutsche Bank)

All of that argued for a bounce in the new year and what a bounce it was. In fact, it was the best start to a year for global equities since 1987.

You might recall that 2018 was the year that USD "cash" became a viable asset class for the first time since the crisis. Only 9% of assets outperformed US 3m Libor last year. Well, as of this week, 98% of global assets have posted a positive return YTD.

(BofAML)

Needless to say, that's in large part attributable to the Fed's dovish pivot and expectations that central banks in general will follow the Fed's lead. Indeed, this week brought fresh evidence to that effect as the RBA's Lowe shifted to a neutral stance and the RBI "shocked" markets with a (politically motivated) rate cut. On Thursday, the BoE's Carney expressed serious concerns about the economic impact of a prospective hard Brexit and you're reminded that last month, the ECB explicitly acknowledged downside risks, opening the door to a new round of TLTROs (targeted long-term refi ops).

For their part, BofAML described the combination as "a central bank blink for the ages" on Thursday.

The question, though, is whether monetary policy has the capacity to cushion markets in the event one or more tail risks are realized.

A persistent worry over the past several years has been that central banks simply haven't normalized policy quick enough, and that when the next downturn finally comes calling, the major CBs will be uncomfortably close to the zero bound (at best) and still mired in negative rates (at worst). Meanwhile, central bank balance sheets remain bloated, ostensibly constraining policymakers' ability to reflate in the event the global economy takes a turn for the worse.

This is the paradox of policy normalization. Suspending market rules in the interest of restoring normal market functioning (which is what central banks did in the wake of the crisis) comes with a tacit obligation to re-emancipate markets at some point in the future. But the longer martial law (if you will) stays in effect, the more atrophied the market becomes. Everyone forgets how things normally work as the exceptional (i.e., ultra-accommodative monetary policy) becomes the "norm".

As central banks' addiction liability accumulates, restoring normal market functioning (and thereby rolling back what amounts to policy protection for the short vol./carry trade in all its various manifestations) becomes an increasingly dangerous proposition. Hence the tendency to push the date of re-emancipation further and further into the future. Of course in doing that, central banks delay the process by which they rebuild their countercyclical ammo (i.e., their capacity to cut rates and expand the balance sheet), thereby risking a scenario where the next downturn comes along and they are constrained in their ability to act. But, again, rebuilding that ammo entails normalizing policy and as we saw in 2018, that normalization process has the potential to itself trigger a downturn if the accompanying weakness in risk assets begins to manifest itself in real economic outcomes (e.g., the wealth effect going into reverse to the detriment of consumer spending, etc.).

This is where we find ourselves now. A recent study by Deutsche Bank looked at what the effect on global growth would be if the tail risks inherent in a trade-related US recession, a no-deal Brexit and/or a policy-induced unwind of all the leverage built up in China were to be realized. Suffice to say the bank's conclusions were not particularly comforting and while the very idea of a "tail risk" means such outcomes are unlikely, the juxtaposition between constrained monetary policy and mounting geopolitical risks is one of the more vexing issues facing markets in 2019.

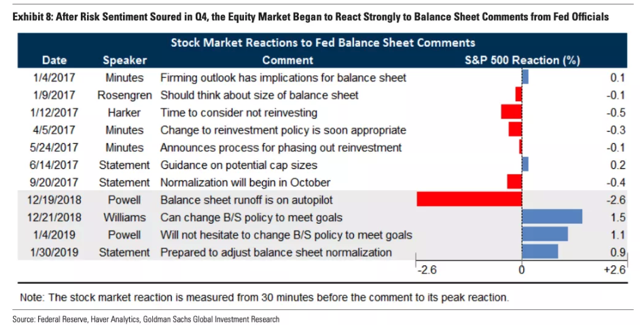

The ECB has few "good" options when it comes to additional easing and Japan arguably as no options at all, although Kuroda would beg to differ. The Fed, by virtue of being the "first mover" on the normalization front, has more leeway. Officials (both past and present) have made it clear that the next move for US rates could be a hike or a cut (the January statement tipped the same thing), but the market is intently focused on the balance sheet. Obviously, you cannot cut rates and proceed apace with balance sheet runoff. That's a contradiction too glaring for anyone to stomach. Here's what BofAML said about that last month:

We do not believe that the scenario of the Fed continuing with the reserve drain while cutting rates is credible. It is generally inadvisable to drive an automatic car with one foot on the brake and one on the Accelerator.

Given that, and given the "special statement" on balance sheet normalization that accompanied the regular January statement, a tweak to the runoff plan seems like a foregone conclusion at this point.

To be clear, there is virtually no convincing evidence to suggest that runoff has had a material mechanical impact on risk assets. It's true that the total tightening impulse in the current cycle is somewhere on the order of 5.5% (using the total rise off the estimated negative 300bp level the shadow rate hit in 2014), but the best estimates I've seen show the cumulative impact of runoff itself equating to just a little more than 1 (that's one) 25bps rate hike.

Additionally, the term premium (which is where the return of duration to the market should theoretically show up, especially in light of increased Treasury supply) has actually fallen, hitting near record lows in Q4.

Rather, the impact on risk assets from balance sheet runoff seems to be almost entirely psychological, as illustrated rather poignantly in the following table from Goldman which shows that nobody cared about this until the issue was amplified by President Trump's "50 Bs" tweet (what you're looking at are the outsized moves around balance sheet chatter in the grey shaded area):

(Goldman)

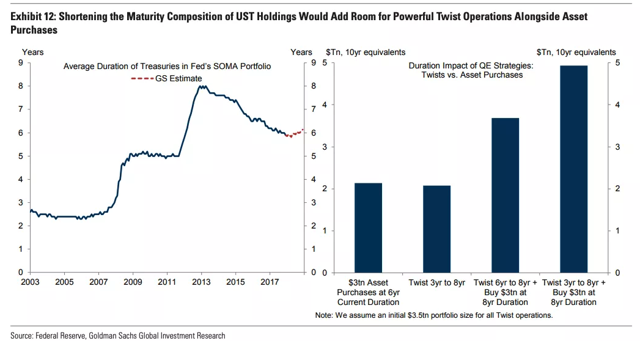

While the debate about how the balance sheet will evolve is obviously many-sided, one thing seems pretty clear. The Fed will likely try to shorten the average duration of the portfolio. This is a long and winding discussion, but for our purposes here, just note that one advantage would be that such a move would open the door to another Operation Twist later. "The motivation would be to provide greater flexibility to lengthen maturity if warranted by an economic downturn," Goldman wrote earlier this month, in a lengthy piece documenting the likely evolution of QT.

On the left below is the average duration of the Fed’s holdings. On the right, Goldman attempts to show you the asset-purchase equivalent of a new twist based on an initial $3.5 trillion portfolio (the two bars on the left) and also the duration impact of a couple of different combinations of twisting and buying (the two bars on the right).

(Goldman)

Clearly, freeing up room for duration extension down the road (by shortening duration now) is desirable. "As a result, we see an eventual deliberate shift toward shorter Treasury maturities— including bills—as likely," Goldman concluded, in their analysis.

That's been echoed by a number of analysts over the course of the last two months.

The overarching point from all of this is that against a backdrop of seemingly permanent political tumult and proliferating concerns about growth, central banks are again pondering the uncomfortable prospect of being forced to reflate the global economy and rescue risk assets.

The fact that stocks went nowhere this week despite the Fed's dovish pivot and clear signs from policymakers (e.g., the RBA's Lowe) that the global bias is no longer towards tighter policy, suggests the market doubts the ability of central banks to offset the myriad headwinds enumerated here at the outset.

That's not necessarily to say market participants doubt the efficacy of monetary policy itself. Rather, the question is more about whether those policies have been exhausted and if they haven't, whether there's a will to push things even further (e.g., to push rates deep into negative territory and/or resort to outright debt monetization).

The next couple of weeks will be key when it comes to getting a read on whether markets are inclined to view central bank dovishness as "sufficient" when it comes to adding risk (i.e., extending the rally) or whether the accommodative policy pivot is viewed as being already priced in after the best January in more than three decades.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario