EM groups will pay heavy price for gorging on debt

Less investment for growth and yet more borrowing beckons

Jonathan Wheatley

© Bloomberg

Emerging-market companies have gorged on debt. Slower global growth and higher funding costs will make servicing that debt harder, just as the amount coming due this year reaches a record high. The result? Less investment for growth and yet more borrowing.

These are some of the concerns raised by the Institute of International Finance, a Washington-based industry body and data gatherer, as it published its quarterly Global Debt Monitor this week.

The world is “pushing at the boundaries of comfortably sustainable debt,” says Sonja Gibbs, managing director at the IIF. “Higher debt levels [in emerging markets] really divert resources from more productive areas. This increasingly worries us.”

The IIF’s data show total global debt — owed by households, governments, non-financial corporates and the financial sector — at $244tn, or 318 per cent of gross domestic product at the end of September, down from a peak of 320 per cent two years earlier.

In some areas, though, borrowing is rising. Of particular concern is the non-financial corporate sector in emerging markets (EMs), where debts are equal to 93.6 per cent of GDP. That is more than among the same group in developed markets, at 91.1 per cent of GDP.

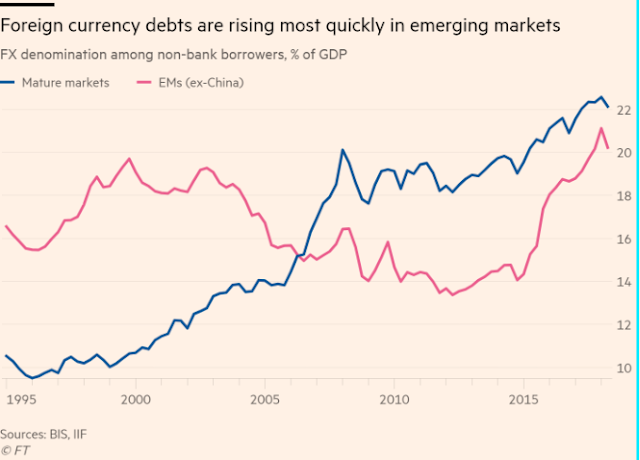

The amount of debt denominated in foreign currencies among all non-bank borrowers in EMs (excluding China, which has little foreign currency debt) has risen quickly to the equivalent of more than 20 per cent of GDP, says the IIF.

This problem is expected to become acute this year, as the amount of debt maturing across EMs reaches its highest level since the IIF began collecting such data in 2014. Of $2.16tn coming due this year, more than $500bn is denominated in foreign currencies.

“In emerging markets, the issue is not the level of debt but the pace of accumulation,” says Emre Tiftik, an IIF economist, pointing to countries such as Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Turkey.

Jim Barrineau, head of EM debt at Schroders, says Turkey offers a great example of a corporate sector with foreign currency debts that must be repaid out of local currency revenues.

This is an age-old problem, described as “original sin” by economists Barry Eichengreen and Ricardo Hausmann after the EM debt crises of the 1990s. Many governments made great efforts to reduce their vulnerabilities over the following two decades — at least until recently.

“When Turkey had its mini-crisis in 2018 the corporate sector became very stressed,” Mr Barrineau says. “To avoid default, the debt is being put on the sovereign balance sheet. That is what we’re seeing in Turkey in stealth mode, and that is what countries with stressed corporate sectors ultimately end up doing.”

In the end, each country has just the one balance sheet. Meeting those obligations may be about to get tougher.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario