As This Bubble Deflates, All Assets Will Be Affected: The One Polity, Two Economies World

by: Roger Salus

Summary

- Western countries are demarcating into two distinct economies, consisting of higher- and lower-tiered earners.

- With the shrinking of the once-strong middle class, the political intelligentsia loses credibility and legitimacy in the eyes of increasing numbers of voters.

- As unconventional parties and candidates gather popularity, our elites grow increasingly defensive, enraged, and unable to constructively deal with events occurring beyond their bubble.

- As the bubble surrounding mainstream politics deflates, economies will be affected, along with assets ranging from currencies to stock markets to precious metals. Nothing is exempt. Be warned.

- With the shrinking of the once-strong middle class, the political intelligentsia loses credibility and legitimacy in the eyes of increasing numbers of voters.

- As unconventional parties and candidates gather popularity, our elites grow increasingly defensive, enraged, and unable to constructively deal with events occurring beyond their bubble.

- As the bubble surrounding mainstream politics deflates, economies will be affected, along with assets ranging from currencies to stock markets to precious metals. Nothing is exempt. Be warned.

As promised, dear readers, your humble author concludes his look at the "two economies" phenomenon by discussing the inevitable political consequences that are already unfolding. The growing class divide within developed economies has been happening since at least the 1960s, but it was the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 that shook the political status quo to its core. Whether that will be good or bad remains to be seen, and open to interpretation. What's not in doubt is that our political class is mortally wounded, and there will be consequences for asset values, whether stocks, precious metals, or even currencies.

Until now, the political elites of developed nations have been either ignorant of, or in outright denial about growing class divisions. In my previous three articles (see here, here, and here), I discussed how outdated economic indicators, like GDP, inflation, and unemployment have disguised the slow stratification of society into two classes due to disappearing job opportunities, punitive living costs, and decreasing social mobility.

Since 2008, the chasm between grass-roots voters and mainstream political elites has grown wider. The result has been the rise of unconventional political parties and candidates in the West and worldwide. This will inevitably affect our investments and asset values.

Brexit, for example, demonstrated how political earthquakes can affect national currencies and precious metals. The Trump White House attests to the fact that previously sacrosanct notions, like freer trade, are no longer sacrosanct. The latest Italian standoff proves that unconventional governments now have the popular backing to challenge the political establishment.

If these developments are not factored into your asset allocations, perhaps it's time they were.

What, We Worry?

We of the developed world are in the midst of epochal political changes. That so few of us realize it is testament only to the extent that our political class is in denial of the fact, and that includes the mainstream media.

The evidence is too extensive to dismiss.

In the US, in the midst of the 2008 economic crisis, voters angrily rejected mainstream politicians, like Hilary Clinton and John McCain, and elected a relative unknown in Barrack Obama. This was not a temporary blip. Come 2016 voters were still rejecting mainstream politicians, like Hilary Clinton and Ted Cruz, in favour of the highly unconventional Donald Trump.

It is critical we don't misunderstand the significance of these events. The mainstream media, for its part, has consistently misinterpreted it. President Obama's election was not, as we were told, a warm embrace of the Democratic Party and a "turn to the left". It was clearly a rejection of the status quo, period. Developments since then have further confirmed this.

Consider that Mr. Obama was elected in the midst of a financial crisis and an unpopular war. In 2008, there was a surge of voter turnout, the highest seen in decades (see here).

By 2012, however, enthusiasm for the President waned as he came to be seen as much more mainstream than many supporters had wished. Voter turnout in 2012 reverted back to pre-2008 numbers (see here). The president easily managed re-election but did so against a most archetypal mainstream Republican challenger, Mitt Romney.

If you're still clinging to the media narrative, then fast forward to 2016. A most unconventional candidate, Donald Trump, shocked the Republican establishment by seizing the party's nomination amidst a storm of inner-party acrimony (see here). Meanwhile, Hilary Clinton, the anointed next president, unexpectedly faced a grassroots revolt that nearly placed Bernie Sanders, himself a most unconventional candidate, on the party's ticket instead. Clinton eventually received the nomination but did so under a cloud of controversy (see here).

Ultimately, the unconventional Donald Trump won the election, despite the deafening jeers of the political establishment. Recent reports even show significant numbers of Obama voters preferring Trump to Clinton in 2016 (see here).

Most recently, the recent US mid-terms saw the unlikely nomination, and then election, of professed 'Democratic Socialist', Alexandra Ocasio Cortez, who unseated the establishment Democratic congressman, Joseph Crowley (see here). The move towards the unconventional continues on, and in every case, the political class is "shocked" by the results.

This shift is not merely a US phenomenon, either.

Since the GFC, so-called "fringe" parties have been gaining momentum year-after-year in Europe. The rising popularity of nationalist and right-wing parties, like the Dutch Freedom Party, True Finns, Swiss People's Party, and the Danish People's Party was first dismissed, and then jeered, by a political establishment watching its own monopoly on power evaporate.

Just as importantly, left-wing "fringe" parties have also seen new-found success since 2008.

From the Greens to Podemos, the rising popularity of leftist parties is undeniable. In Greece, the far-left SYRIZA, led by the academic Marxist, Alexis Tsipras, actually assumed power.

Even boring, conventional Germany is seeing its political establishment turned on its head. Ten years separated from the GFC, unconventional parties perform as never before. From the right-wing AfD to the leftist Greens, fringe parties are not merely pecking away at mainstream German parties, they're now threatening to topple them (see here and here).

Meanwhile, in Italy, a most unlikely coalition between Five Star and the Northern League has taken power and is challenging Brussels on everything from fiscal policy to immigration.

Of course, possibly the most shocking development was the UK's Brexit referendum in which Britons voted to leave the EU. Needless to say, the establishment was "shocked" when the Brexit votes were tallied.

More localized separatist movements have also grown in various jurisdictions, like Scotland and Catalonia. Indeed, Italy's Northern League initially cut its teeth as a party by advocating for regional Independence.

If you've been watching network news you're likely aware of the aforementioned developments, but you may be completely unaware that what we're seeing is the incremental overturning of a political establishment that has existed for half a century, an establishment that includes, of course, network news.

How We Got Here

So, what gives?

How is it that the political scene is so prone to upheaval amidst what is supposedly one of the longest economic expansions in history? After all, GDP growth is positive, unemployment is at "record lows", and inflation is non-existent. This isn't the way it's supposed to happen.

In my three previous article (see here, here, and here), I demonstrated that many measures used to gauge the health of the economy - namely GDP, inflation, and unemployment - are either outdated or hopelessly inaccurate. The incremental stratification of nations into two distinct economies is simply not built into the models.

GDP numbers post-2008 have been mostly positive. However, in many developed countries, like the US, UK, Canada, and Australia, they mask many nations' over-reliance on consumer spending to produce those positive numbers. Worse, they mask the fact that the meager post-crisis GDP growth is mostly attributable to spending by the lowest-tiered earners, thanks largely to unsustainable consumer debt, decreased savings, or plundered savings.

The inflation rate, which central bankers continuously insist is "too low", is deceptive as well. Attempts to accurately account for "hedonic adjustments" or "substitution", while perhaps well-intended, have had the effect of confusing price increases with living standards and with living costs.

These are not the same things, yet "inflation" is frequently paraded as a measure of them all.

In a two economies world, the net result has been that for high earners wage-increases have kept up rather well with living standards and living costs, but bottom-tiered earners are being crushed. All the hedonic adjustments in the world can't disguise the fact that 50 years ago a sole bread-winner could support a family and still hope to retire. Today, for much of the population, two bread-winners are needed if families are to merely keep up with advancing technologies and living costs, and even then, ever fewer can realistically hope to retire.

Unemployment numbers, too, are misused by our political class, whether by politicians, bureaucrats, or the media. The typical model of "employment" that existed in the 1950s and 1960s no longer exists, yet it is still expected to continue functioning in economic models exactly as it did then, by using the famous/infamous Philips Curve, for example.

Employment once referred to permanent full-time work, a livable wage, and a retirement plan.

For the unskilled, it represented a path to the middle-class for those possessing some combination of work ethic, loyalty, and prudence. It no longer does. In a two economies world, the old standard of employment is gone, likely forever, for not only low-skilled workers but increasingly for the skilled as well.

Our political class has been rhetorically aware of the hollowing out of the middle class but has been impotent to address the issue beyond the realm of, well, rhetoric. The media, in particular, is in outright denial. Whether for reasons of laziness, incompetence, or worse, our media routinely trumpets GDP, inflation, and unemployment without looking closer at the big picture.

Indeed, I've also shown (see here) that, as an inseparable part of the political establishment, the media often cynically touts these numbers selectively, either trumpeting or ignoring them, depending on which party it suits.

Don't Get Too Comfortable

So, it is. Given the decades-long deterioration of economic conditions for ever-larger swaths of the economy, one would expect the intelligentsia to be prepared for, and able to deal with, challenges from the fringes of the political spectrum. But clearly, events like Brexit and Trump take them by surprise, again and again, and again and again, the political establishment responds only with rage. Presumably, if the political class had any solutions of its own, it would have instituted them by now. It doesn't and hasn't. And hence, a political battle has begun in earnest.

To be clear, this article is not an endorsement of any party, mainstream, or otherwise. Rather, our financial well-being depends on recognizing and accepting the macro trend now sweeping the developed world. No one is asking us whether we like it.

Simply put, expect more of the upheavals like we have seen since 2008.

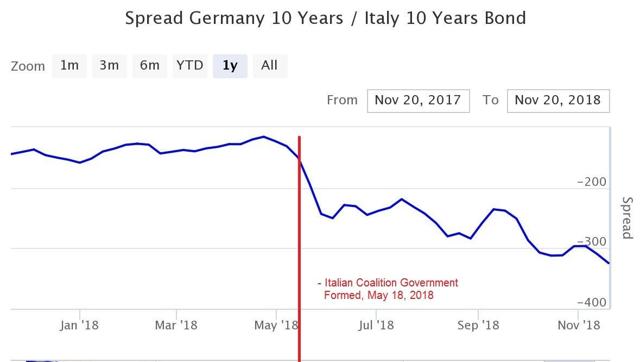

Perhaps the most stunning of these post-2008 upheavals was the UK's vote for Brexit, essentially rejecting membership in the EU. The aftermath in the markets was nothing short of spectacular. The following day the UK pound dropped 8%, its biggest one-day drop since the collapse of Bretton Woods (see here), but more importantly, the pound has not come close to recovering from its lows two and one half years later. From The Federal Reserve.

US/UK Exchange Rate 2016 - Present

Moreover, the London FTSE stock exchange lost 3% by the end of the first day, though it had been down as much as 7% at the start of trading. Perhaps surprisingly, most European markets dropped even harder, with the German DAX losing almost 7% and Paris losing 8% (see here). The price of gold, meanwhile, surged 5% in a single day.

Since then, of course, normalcy has mostly returned to the stock markets, though the pound still remains markedly lower (see above). The longer-term effects of a potential Brexit, meanwhile, are proving to be more difficult to quantify (see here and here).

On the West side of the Atlantic, the election of Donald Trump in November 2016 created other interesting reactions. As results came in, there was initial shock (again, "shock"), as Dow futures fell up to 750 points. Meanwhile, global markets also dropped sharply. However, those moves,

particularly in US markets, quickly whipsawed, erasing those losses before finishing higher.

Policy-wise, Mr. Trump appears to be somewhat serious about pre-election threats to challenge the trade paradigm in place for roughly 30 years. Granted, with regard to NAFTA, some have reasonably labeled the president's changes as largely "cosmetic" (see here), but his standoff with China is proving to be anything but. The reverberations of this move have only begun, and only time will tell how it ends.

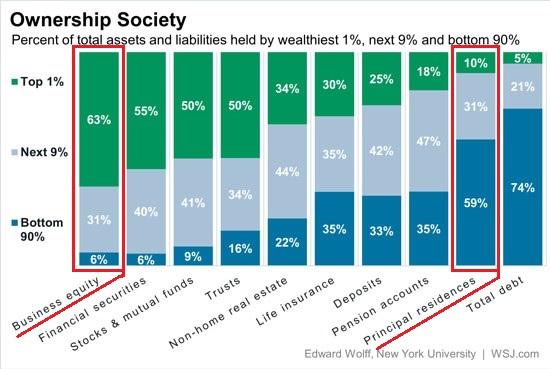

Meanwhile, the situation in Italy demands particular attention. It's becoming clear that the new coalition believes it has the popular support to defy the European political establishment from fiscal policy to immigration.

Not even the dramatic deterioration in Italian government bond spreads has caused the coalition to blink. Since May 2018, when the current Italian coalition was announced, bond spreads vis-a-vis the German Bund have not recovered:

.

Source: World Government Bonds

This is the crux of it. It's not just that unconventional parties and candidates are getting elected, it's that they are more willing to take the unconventional actions voters elect them to take. As a visibly impotent political class spits ever more contempt upon elected governments (and, by implication, those who elect them), whether left or right, it only appears to lose further credibility and legitimacy (see here and here) and accelerates its own decline.

As I mentioned previously, the current political upheavals we are seeing are occurring in the midst of one of the longest economic expansions in history. A recession is statistically overdue, and that may be when the real fireworks start.

Takeaways For Investors

There are three major takeaways that investors should be aware of:

1) Thus far, globally, stock markets have largely shaken off the more significant electoral shocks. For example, a sharp drop in Asian markets made headlines after Trump's November 2016 US election.

However, the whipsaw action back to the upside was just as dramatic, and can be seen nicely in the following Nikkei chart, for example:

Nikkei 255, Q4 2016

Source: Macrotrends

2) The few assets that have been affected longer-term are confined to the specific countries where the electoral shock occurred. Weakness in the pound sterling, for example, has largely been the principal consequence of the Brexit vote. Globally, stock markets have largely recovered since the UK referendum, even those in the UK and Continental Europe.

Similarly, the main consequence of the new Italian coalition has been the aforementioned widening of Italian government bond spreads, though the potential for wider contagion is at least conceivable.

3) Safe-haven flight has also tended to be fleeting, with the dollar often (though not always) filling that role as a preferred asset. In the immediate aftermath of first, the Brexit vote, and more recently, the Italian coalition announcement, the euro experienced sudden drops of 3.16% and 2%, respectively, against the US dollar before eventually normalizing (see here).

The election of Donald Trump initially had the opposite effect, however, as the expectation of higher US deficits initially weakened the US dollar. However, that trend, too, reversed once new Fed Chairman Powell demonstrated continued commitment to normalizing US monetary policy.

Precious metals, of course, represent another perceived safe haven. And in just the first two weeks following the Brexit vote, gold increased 7.6%, reaching US $1370/oz on July 6th. Since then, however, gold moved back down and has not repeated that post-Brexit high since. This adds further weight to the conclusion that political shocks have thus far been shrugged off by markets, save for short-term reactions.

London Gold Fixing Price 2016 - Present

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

Conclusión

Thus far, there have been several major political earthquakes in developed countries, and countless minor tremors. Market effects, however, have been largely temporary or localized to specific countries.

The larger trend, however, is clear: the unraveling of the Western political establishment is underway.

However, it is also a gradual unraveling, and not cause for immediate panic. That said, we can't assume that markets will indefinitely shrug-off political shocks.

By way of currencies, I believe the euro is most vulnerable.

The current spat with Italy's coalition is only the tip of the iceberg. Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland are approaching outright revolt against Brussels on immigration. Catalonians in September 2017 voted for independence and were violently crushed by the Spanish government. Meanwhile, French President Macron, the darling of the political establishment, now sports approval ratings of 21%, and his party currently trails Marine Le Pen's in popularity (see here). This, as voter turnout for EU parliamentary elections has declined in every single vote over four decades (see here).

It's unclear that Europe's political elites can realistically rely on either financial threats (shades of Greece, 2015) or baton-wielding riot troops (shades of Catalonia 2017) to hold an increasingly unpopular status quo together.

Catalonia, Sept. 2017, Source: PRESSTV

As we saw in the wake of Brexit, currencies can undergo major moves when voters don't behave as their "betters" expect. The euro is a more widely held currency than the pound, so expect the reverberations to be even more extreme should the eurozone experience a major disruption, such as a country leaving.

Stock markets have also shown fits of volatility. From the whipsaw action following Donald Trump's election to the steep drops post-Brexit, moves can be big and happen fast. It's also true, however, most of these moves have stabilized with time. Traders may wish to try to profit from such moves, while long-term investors may wish to merely ignore them. However, the current rising rate environment presents a brand new variable, and thus stocks look increasingly risky from your humble author's perspective.

As for precious metals, it seems they will always retain some safe-haven appeal. As we saw post-Brexit, gold's status as a safe haven is still alive in the minds of millions. It has recently shown weakness as the Federal Reserve continues its rate-tightening policy, but short-term it at least appears to have found a bottom. Such levels might present buying opportunities for gold bugs.

Frustratingly, while we can clearly see that the Western political establishment is in its death-throes, we cannot clearly see what direction(s) voters will take near-term. Of course, if we knew which unconventional direction any given country might take we could take preparatory measures. But we don't know.

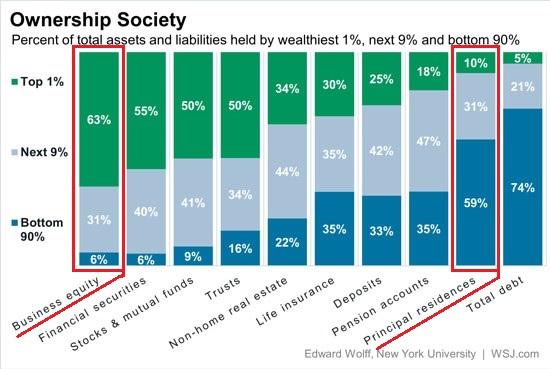

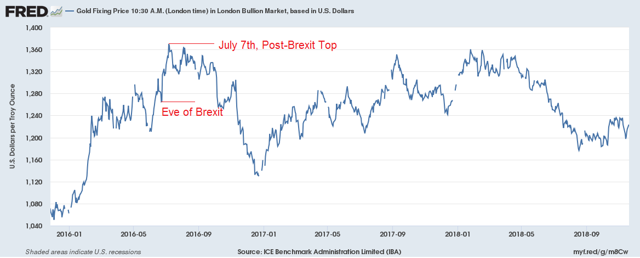

What we do know is this: Warnings of financial turmoil from our elites will not frighten voters away from the unconventional any longer. This, too, is a function of our "two economies". With 10% of Americans, for example, owning 91% of stocks and mutual funds (see below) it would be unwise to expect restraint from those who increasingly believe they have little to lose.

Source: Wall Street Journal

We can no longer deny that greater numbers no longer see the political class as elected representatives, public servants, or even fellow countrymen. Both elites and the modern state apparatus are perceived by more and more as serving career technocrats, financially endowed lobbyists, political correctness high priests, or varied special interests. Citizens who do not fall within any of these categories - i.e. who exist outside the bubble - have become marginalized and despised, and they know it.

The Western intelligentsia seems unable to fathom what is happening from within its bubble. Internally its rigid academic "correctness" on all matters remains unquestioned. Continued use of the aforementioned dubious economic measures has only contributed to this disconnect.

Thus, challenges to the status quo are routinely attacked as evil outside forces, but such attacks resonate less and less with each passing year.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario