Red Hot China Mailbag

By John Mauldin

An odd aspect of being a writer is you never know in advance what will excite readers. I’ve written letters I thought very provocative only to draw mostly yawns.

Last week’s trade deficit letter lit some fireworks. The response was immediate and, in many cases, quite passionate in both directions. I got emails from old friends and longtime readers saying it was my best letter in years. Others said I had lost my marbles or gone over to the dark side. In fact, my whole China series has generated a lot of response. Evidently, I kicked the anthill.

I always appreciate feedback, even when it’s negative. Our staff collects feedback from social media, the comment threads on our website, email, and probably other ways unknown to me. They dutifully assemble it into one document and distribute it to the team. When that email hits my inbox, it gets top priority and I read them all. I always learn a great deal. An amazing number of intelligent, articulate people read these letters. So today, I’ll feature some reader comments from recent weeks and explain further where my point perhaps wasn’t clear.

While it is nearly always dangerous to make broad associations, the responses generally broke down into “John, you said it clearly and I wish everyone would read this,” and “John, you simply don’t understand the danger that China is, either geopolitically or trade wise, and we have to stop their cheating.”

As I read the responses, I realized that my letter didn’t have all the nuance I intended. Further, I needed to refine some of my own thinking. In the interest of brevity, I will ignore the positive comments and focus on a few (out of many) that pushed back. I picked a few examples because a proper tour of tariffs would take a complete book

I should note we’ve lightly edited some of these readers for clarity. With that, let’s jump right in.

Predatory Practices

Here’s Lawrence Brady responding to The Trade Deficit Isn’t the Boogeyman.

In purely economic terms, I could not agree more. However, there is a bigger game taking place here that supersedes the discussion in only GDP terms.

In a level playing field, specialization is the most effective way of creating opportunities and minimizing costs. In this case, there is more at stake since there is no international Sherman Antitrust Act that precludes monopolization and eventual control of all aspects of the supply chain.

China’s predatory practices through unregulated production standards/industrial espionage and violation of US security protocols is indicative of economic warfare. Admittedly better than the alternative of nuclear or conventional actions, the results can be the same if not checked.

So, I think we need to look beyond import/export ratios and currency reserves. It is a Cold War by other means dictating a new paradigm in analysis.

John: Lawrence’s note represents many others who said they understood about trade deficits, but think China is a unique threat that deserves a stronger response.

Let me rephrase that for emphasis: Using tariffs to reduce the trade deficit is economically irrational. It won’t work. Tariffs do have their uses, from time to time, but are dangerous if used haphazardly or in the wrong circumstances. I was not against tariffs per se, but against tariffs as a weapon against “the trade deficit.” Which is not a problem, at least if yours is the reserve currency. Especially if you have the world’s reserve currency.

I suppose carefully-targeted tariffs could be part of the answer to the problems Lawrence describes, but that’s not what the US is doing. We are, in effect, firing artillery shells at paper targets. It’s loud and emotionally satisfying but doesn’t hit the real target further downrange. It also hurts innocent bystanders who happen to be in the area.

Part of the real problem here is that China gets to play by a different rulebook. The World Trade Organization lets member nations define themselves as “developing” countries. It’s kind of like an open book test where you know the questions beforehand, but some other students have to study. WTO rules give developing countries, as China considers itself, certain additional rights. (Explaining them would get us deep in the weeds; click here if you want to geek out.)

Is China a developing country? That’s complicated. Much of the vast, mostly impoverished interior and Far West certainly isn’t “developed.” But the wealthy eastern coast and a few hundred miles inland is as developed as many Western countries. So, it’s really both.

You could say the same about the US, by the way. New York and San Francisco (and Dallas!) are world-class cities while parts of Appalachia, Maine, and the rural South are relatively as undeveloped as China’s poorer regions. Should the US call itself a developing country and claim WTO relief? We might have a case if we use the Chinese standard. By that standard, every country is developing as income distribution varies by region.

What we really need is for China to admit it no longer deserves the same protections other truly developing countries receive under WTO. Beijing wants to be a great power? Fine. Put on your big boy pants and you can have a seat at the adult table.

In my view, tariffs are not the way to nudge China in this direction. They are a blunt instrument in a situation that needs more finesse. US strategy seems directed at making Xi Jinping feel so much pain that he will surrender and do what he’s told. That will never happen. Xi may be president for life, but he still has political constraints.

If tariffs won’t work, what will? Patient, methodical, and private negotiations in alliance with the other countries whom China’s practices are harming. Europe and the rest of the world have the same issues. That would take time, but I think stand a much better chance of success. Tariffs should only be used as a last resort.

Better yet, it would avoid the damage the tariffs are already beginning to impose. Which brings us to the next letter...

War Talk

Joann Middlestead writes:

The problem isn't economics. The problem with China is the theft of intellectual property—and the fact that IF war were to break out, we could conceivably find ourselves like the southern states versus the North, who had all the manufacturing capabilities which enabled them to win the war.

As China becomes more and more modernized and more and more competitive, they WILL attempt to become the world superpower (that is without doubt). So, the USA needs to return jobs onshore—with the ability to manufacture what we would need to both enable us to win a war using our own resources and the ability to feed and clothe the populace while said war is ongoing.

John: As noted above, I agree with Joann on intellectual property. I want to gently dispute the war talk, though.

First, China has no interest in starting a war with the US. If by some chance it does get frisky, that war would look nothing like the Civil War or even World War II. It would happen mostly in cyberspace and outer space. Our domestic manufacturing base would not be the kind of edge it was a century or two ago. Those who think so are like generals who are fighting the last war.

Feeding the population is no problem, either. The US is a net food exporter. We might have to do without some delicacies (though I can’t think of any I would miss), but we won’t starve without imports.

But what really bothers me about Joann’s note (and the many others like it) is this casual willingness to go to war—either trade war or military conflict. War hurts people on both sides. We should do all we can to avoid it.

A full-on trade war with China would not simply mean tightening our belts. We would be sacrificing large parts of our own economy and population, putting entire companies and even industries out of business.

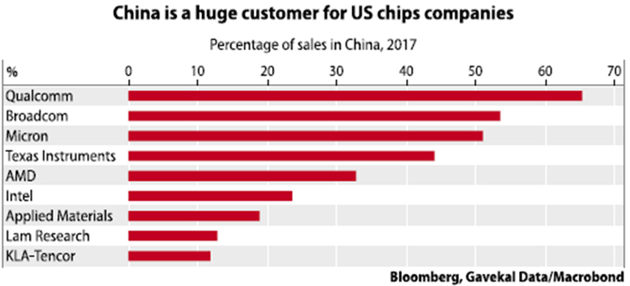

Here’s a Gavekal chart showing how dependent US semiconductor firms are on China sales.

Some of these companies will die if we cut off trade with China or China applies similar tariffs. Most of these companies have very sophisticated competitors in other countries. They will go out of business, their workers will lose jobs, and their share prices will drop to zero. Numerous small businesses that supply them will go bankrupt.

That shock alone might push the economy into recession and stock prices into a real bear market, but plenty of other sectors would get hurt as well.

Many trade hawks who want to take that risk seem to ignore the costs. They are wrong and, given our other social tensions, I fear catastrophe if we choose to bring this on ourselves.

If you disagree, let me ask you this: What are you willing to give up? Is sticking it to China worth losing your job, or having your taxes rise and your income drop? If you own a business, are you ready to find domestic sources for everything you buy? And pay higher prices that you can’t pass on to your customers because they’ll be struggling, too?

All that is unnecessary. We can get what we want from China without imposing such pain on ourselves. But it will require a different negotiating strategy than we’ve seen so far.

Quality Control

David Oldham writes:

China seem to be flooding the world with garbage quality goods, or do they only send their garbage to the UK? Almost everything marked “Made in China” is exceedingly poor quality with the exception of Apple products, which I assume is subject to Apple quality control inspectors. This has become a real problem in the UK, especially where safety is an important factor—boat and rigging parts for example.

I understand a large portion of Chinese goods exported to the UK end up returning to China for recycling. I wonder if all the plastic destined for recycle treatment ends up in our oceans. I have a very different view of China than you, John. To me, they are a ginormous public pest.

John: I partly agree with you, David. Certainly, many of the products China exports to the West are low-quality or even counterfeit. That is part of the intellectual property reforms the Trump administration is demanding. It’s a serious problem, as you say.

I would dispute that “almost everything” China exports is low-quality. The government has been aggressively pushing businesses (state-owned and otherwise) to make more sophisticated goods. They have little choice, in fact. Other Asian and African countries are quickly taking market share in the relatively simple manufacturing segments because their labor costs are so much lower than China’s. That will continue.

This brings me to a point my friend Andy Kessler made so well in the Wall Street Journal last week. It is not actually desirable to produce every low-margin product in the US. As he said:

That’s the fallacy of today’s tariff war with China: It is meant to save jobs but ends up destroying better ones. By now, it feels like every Chinese import, save iPhones, are subject to tariffs under Section 301. As President Trump said in February, “I want to bring the steel industry back into our country. If that takes tariffs, let it take tariffs, OK? Maybe it will cost a little bit more, but we’ll have jobs.”

But not all jobs are equally desirable. It’s profits, not sales, that create wealth. We should invest along the productivity fabric. Jobs for jobs’ sake destroys wealth. Saving Detroit was a mistake. Should Nike shoes really be made in Oregon?

We should take a page out of Lee Kuan Yew’s playbook for Singapore and think about what jobs and businesses fit best for the US. Singapore was once a nation of assemblers and T-shirt makers. But over time, it moved up the business food chain and is now among the most advanced.

Ironically, some textile work is coming back to US, but it is automated and brings relatively few jobs. Formerly labor-intensive assembly and manufacturing work is coming back to the US, but the jobs, wages, and profits are further up the scale.

Manifest Destiny

Jeffrey Ho writes:

I just completed a month-long, 2500-mile journey across western China. Signs of an economic boom are everywhere. While there are no Tier 1 or 2 cities in the west (only two western cities, Lanzhou and Urumqi, are considered Tier 3), even tiny cities of a million or less now sport brand new, modern train/bus stations and airports rivaling or surpassing America’s best.

A massive construction boom is evident all across the classic Silk Road. Small towns that have not seen a new building in 50 or 100 years are now being rebuilt with modern high-rise condominiums right alongside the old. What they do have in Gansu, Qinghai, and Xinjiang Provinces is space. Xinjiang, the westernmost province, is 3-times the size of France.

Gansu, once considered an impoverished backwater area that was largely desert is now a green hinterland as modern irrigation and farming techniques have tamed the waters of the Yellow River. To put it in perspective, Lanzhou, the capital of Gansu Province, is the geographic center of China. This means that as modern engineering and agricultural progress turn more of the desert into productive land, China is just beginning to realize their Manifest Destiny.

The ride on the high-speed train was almost boring. You couldn’t tell that you were barreling across the desert at 130mph except for the LED indicator inside the cabin. My fellow passengers were all seated in their assigned seats with no one laying in the aisles, no agricultural produce or live animals, and the only annoyance was perhaps the conductors incessantly making sure that overhead baggage were perfectly in place. If there is one sign that China has achieved their greatest aspiration to be a first world nation, this is it.

John: Thank you for that on-the-scene report, Jeffrey. First let me say that I’m jealous. I wish I had a month to do that. Or maybe I should just make a decision and take a month. I especially like the part about “tiny” cities of a million or less! While I have not ridden the trains in China, I’ve been all over Europe by train. The speed and comfort is almost unimaginable to most Americans. Why we insist on either flying or driving everywhere is beyond me. I much prefer trains when available.

More interesting, perhaps, is the idea that China’s east-to-west development mirrors the “manifest destiny” that drove the US to expand in the same direction, and for similar reasons: abundant, inexpensive land and natural resources. One difference is we had an ocean waiting over there while China has mountains and deserts. However, the One Belt, One Road projects are opening China’s western edge much like the Pacific gave the US new export markets.

And as the OBOR extends toward European markets and literally the entire Eurasian continent, it will inevitably draw investment, entrepreneurial talent, and even more construction and infrastructure. The growth potential is staggering.

There

I wish I had time and space to include more letters. We actually had four others in the first draft, but we also need to keep the letters a reasonable length. If you responded, rest assured I read your comments and thought about them. I’m well into my 19th year of writing this letter, and every time I write as if I am talking to my best friend. When you write back, it is like I’m reading a letter from one of my closest friends. Thank you for your time and attention in a world where both are ever more precious. I recognize their true value.

Shane and I will go to Puerto Rico in less than two weeks, then come back to Dallas for a few days before I catch a plane to Frankfurt where I will speak to a large group of institutional investors. I know I have a few other trips that aren’t scheduled as yet, but they are clearly going to be in my future.

Sunday evening, I will be having dinner with my great friends Steve Blumenthal and Steve Cucchiaro, who will both be in town for the ETF Strategy Summit. I’m doing the Monday keynote at lunch. Be sure and look me up if you’re there.

About a month ago, before I entered my current not-drinking phase, I was sitting outside at the nearby Stoneleigh P, which I think of as our local “Cheers” bar. Shane was out of town and it’s easy for me to walk there and get good food.

One great thing about the Stoneleigh P is that patrons choose the music, and many are from my generation. The greatest playlists ever. I was sitting outside and an old Roger Miller (born down the road in Fort Worth) song came on. The young wait staff clearly didn’t understand why a few of the older clientele were singing or humming along.

Then all of a sudden, as if doubling down on Miller’s songs that night, you hear him starting to sing “Trailers for sale or rent…” from King of the Road. Totally unprompted, at least a half-dozen of us began singing along, getting louder as we went. It was a generational experience of a song remembered from our youth, when the radio was king.

Third boxcar, midnight train, destination, Bangor, Maine. Old worn-out suit and shoes, I don’t pay no union dues.

This may seem small, but it made me happy to be alive and with my “tribe,” even though I didn’t know one of them. And I would point out that my tribe, at least that night, was very multicultural. Our backgrounds didn’t matter; our common memories united us. We went back, however briefly, to a time when this country wasn’t divided by left and right. The music brought us together. It was a great evening.

It’s time to hit the send button. I hope you have a great week and create some of your own memories.

Your man of means by no means, king-of-his-own road analyst,

John Mauldin

Chairman, Mauldin Economics |

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario