The Bond Selloff That Nobody Noticed

by: The Heisenberg

- Amid last week's global risk-on euphoria, a Treasury selloff got lost in the shuffle.

- Never forget that a bond rout preceded the February VIX spike.

- Some analysts think they're hearing echoes of that episode.

- Here's an in-depth discussion complete with all the visuals you need to understand what is and what isn't potentially problematic.

- Never forget that a bond rout preceded the February VIX spike.

- Some analysts think they're hearing echoes of that episode.

- Here's an in-depth discussion complete with all the visuals you need to understand what is and what isn't potentially problematic.

At least there is a simple and intuitive transmission mechanism directly from yields on US Treasuries into prices for other assets, whereas we see no equivalent obvious direct transmission mechanism from the central bank’s balance sheet to risk asset prices.

That's from Credit Suisse's Kasper Bartholdy, who, in an emerging market (hereafter "EM") strategy note dated September 19, took direct aim at the idea that the wind down of G4 central bank balance sheets is the proximate cause of the turmoil in EM and threatens to undermine risk assets in the months ahead.

Generally speaking, analysts worry that just as the expansion of G4 central bank balance sheets was accompanied by a rally in risk assets of all stripes, the contraction of those same balance sheets will have the opposite effect, as investors move back up the same quality ladder they scrambled down during the QE years. Kasper doesn't necessarily agree for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that he's not even sure it makes sense to talk about balance sheet unwind just yet. Consider this excerpt from the same note:

We also question the whole notion that the sum of the G4 central banks’ balance sheets can really meaningfully be said to be falling at this stage. The ECB, the BOJ, and the central bank of China have all continuously been expanding their balance sheet this year. Only the Fed has reduced its balance sheet in local currency terms. If we compute the sum of G4 central bank balance sheets by converting local-currency data for all days into dollars at the set of exchange rates that applied at the end of last year, we find that on that measure there has been no shrinkage in the sum of the G4 central bank balance sheets in recent months.

I tend to disagree with that way of conceptualizing things, but Bartholdy's overarching point is that if you want to know what to watch for when it comes to warning signs for risk assets, it might make more sense to eschew the obsession with quantitative tightening in favor of a focus on Treasury yields. Here's the key excerpt:

Our broad view is risk markets, including the markets for EM assets, can live with the Fed balance sheet reduction and rate increases that lie ahead for the remainder of the year on the condition that the pickup in both US wage growth and term risk premia in the UST market remain slow, and the market’s views on the neutral Funds rate is not shaken in a major way. When and if that condition is violated, perhaps in response to a string of very strong US wage data, real yields across the US curve may rise sufficiently to cause a major problem for all risk assets, not least in EM space. However, we see no obvious reason at present to expect sharp US wage acceleration to play out exactly in the months between now and the end of the year.

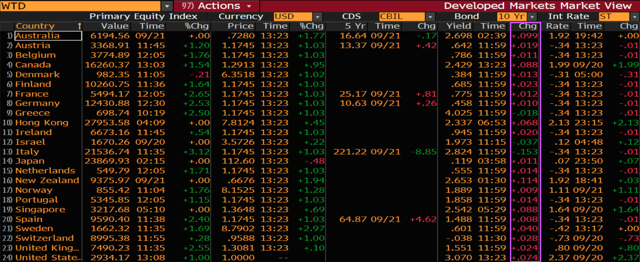

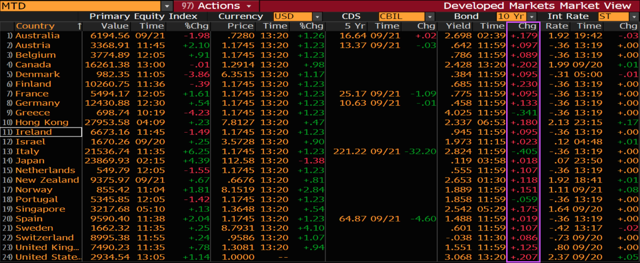

Those interested in the tedious details can read a bit more here, but what I found particularly amusing about Kasper's analysis is that it happened to make the rounds during a week that featured a selloff in US Treasurys (TLT) and other developed market bonds:

On the month, the picture looks like this:

One of the interesting things about this week was that the dollar (UUP) failed to respond to rising U.S. yields. I talked a bit about why that might be the case in a Thursday post for this platform called "Heads Up: Narrative Shift Alert".

It's possible that higher yields abroad and renewed expectations of developed market monetary policy convergence are sapping demand for the long end of the U.S. Treasury curve. It's also possible that this week, the risk-on move catalyzed in part by dollar weakness reduced the appeal of safe haven Treasurys. Also note that the causation works both ways there. Reduced demand for USD assets (i.e., Treasurys) is USD negative. A weaker dollar begets more risk-on sentiment, in a loop. Additionally, the dollar is negatively correlated to global growth, so stimulus rumors out of China and the reflation hope those rumors engendered, likely played negative for the greenback as well. Finally, it's possible that folks are starting to refocus on the U.S. fiscal path and on the prospect of the Trump administration talking down the dollar in an effort to avoid a scenario where the stronger greenback waters down the tariffs on China.

But the simplest explanation for dollar weakness in the face of rising U.S. rates this week is probably that real yields (to which the dollar responds) essentially went sideways, even as nominals widened. Here's nominal yields and real yields, normalized from August 12, and plotted with the Bloomberg dollar index:

Now, here's breakevens:

Is the rise in breakevens really down to reflation optimism? The timing of the spike in the chart above certainly seems to suggest so, considering it coincided with rising crude prices, but a more nuanced discussion finds market participants pondering the elusive term premium. Here's what a strategist at one of the major banks told me on Friday:

It was strange breakevens were widening so much. Breakevens widening was because nominals were selling off and real rates were steady, and the dollar responds to real rates. This could be just the term premium trade in nominals and nothing to do with inflation. Breakevens are just a casualty of that.

Bloomberg's Luke Kawa noted something similar in his weekly newsletter. To wit:

China isn’t the only place where a reduction in overseas risk has allowed for a more positive stance, to the detriment of safe debt. The extent to which the situation in Italy has actually improved is debatable – but the headlines have been supportive enough for BlackRock to go long on the embattled nation’s sovereign bonds. The receding of risk in Europe's periphery has also allowed core rates to rise, as investors rotate out of safe assets. Japanese investors in particular may be back in European debt in earnest after a short-term hiatus. The hedging costs certainly point in that direction.

Under this lens, it’s no surprise that risk assets have been able to weather rising yields so well. At the same time, a decomposition of Treasury yields doesn’t support that sunny a view. A rise in the term premium – the part of longer-term yields we can’t really explain – appears to be the proximate cause of the rise in rates. Despite the seemingly positive newsflow, higher yields for reasons we can’t quite put our fingers on might be cause for worry.

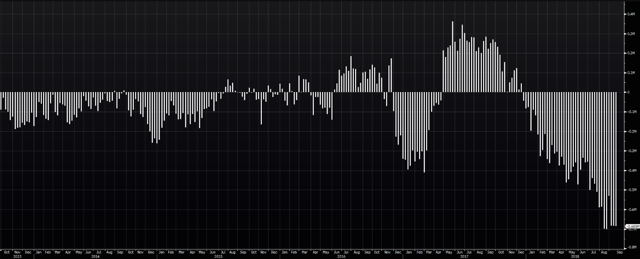

For reference, here's a chart that shows the rise in 10Y yields along with the rise in an estimate of the term premium from late August through Friday:

That's what my analyst friend and also what Luke are talking about when they attribute this week's selloff in Treasurys to the term premium trade.

So what does all of this mean? Well, go back up and read the excerpts from Credit Suisse's Kasper Bartholdy again. The good news for risk assets (e.g., U.S. stocks) is that real yields are still rangebound and haven't moved above their May peak. A sharp rise in real yields would present a "real" (pardon the pun) problem for equities.

That said, this is anything but cut and dry. Remember, real yields have become a function of inflation expectations to the extent price pressures force the Fed to lean hawkish. That's why you want to keep a close eye on wage growth, which is rising at the fastest annual pace since 2009, according to the average hourly earnings print that accompanied the August jobs report.

Here's Bartholdy tying all of this together for you:

The Fed Funds rate is far lower now (about 2%) than it was in 2006 (the Fed raised it to 5.25% in that year). Among the factors that are currently keeping TIPS yields contained and the Fed funds rate low by pre-2008 “strong-economy-standards” is a widely held perception (both within and outside the Fed) that the neutral short-term real interest rate has fallen over time. That rate is, rightly or wrongly, widely perceived to be much lower now than it was in 2006.

Against that background we find it probable that even in the presence of sustained Fed balance sheet reduction in the period ahead, TIPS yields will get back to 2006 levels only if the Fed’s and market participants’ estimates of the neutral Funds rate rises notably, and that will in turn probably require a substantial acceleration in US wage growth or other measures of US inflationary pressure.

When it comes to the term premium, it's interesting that Bartholdy seems to at least partially discount the fact that Fed balance sheet rundown necessarily entails private, price-sensitive investors shouldering a larger percentage of the burden when it comes to absorbing new supply. Considering the deteriorating U.S. fiscal position and the distinct possibility that China will be less enthusiastic about buying U.S. debt in the face of the trade war, one might reasonably expect the term premium to rebuild going forward, although if you follow this debate, you know that expectations for a rebuilding of the term premium have been pushed back time and time again by analysts who seem perpetually perplexed at how suppressed it remains.

In any event, as you ponder the risk-on mood that dominated global markets last week, it's important to note that it unfolded against a backdrop of a meaningful selloff in Treasurys. Jeff Gundlach's interest was piqued and he thinks the financial media might be a bit slow on the uptake:

Do recall that it was just last week when Gundlach suggested that stretched short positioning in the long end could catalyze a "monumental" short squeeze, potentially driving 10Y yields down to 2.25%. So much for that.

For what it's worth, specs extended their shorts in the long end during the week ended Tuesday. Here's the updated TY short:

Don't forget that a brutal bond selloff presaged the February VIX quake. As I never tire of reminding you (most recently here), it was the above-consensus average hourly earnings print that accompanied the January jobs report on February 2 that ultimately led to the chaos which unfolded on Monday, February 5. That hotter-than-expected wage growth print exacerbated nascent fears of inflation and here we are staring at a similar situation headed into next week's Fed meeting and just a couple of weeks out from the next jobs report.

So as you bask in the glory of the convergence trade and the relief that trade entails for downtrodden ex-U.S. equities, do try to read the tea leaves on the burgeoning bond rout.

With that, I'll leave you with an excerpt from the latest note penned by SocGen's incorrigible (but exceedingly affable) bear Albert Edwards:

We have been here before: in early February similarly strong wage data spiked bond yields higher causing a temporary slump in equities. So while we ponder whether the bond bull market is really over (which I doubt… at least yet), the more immediate concern should be what level of bond yields will trigger an equity market slump.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario