Riding the rollercoaster

How to put bitcoin into perspective

The best-known cryptocurrency has been a failure as a means of payment, but thrilling for speculators

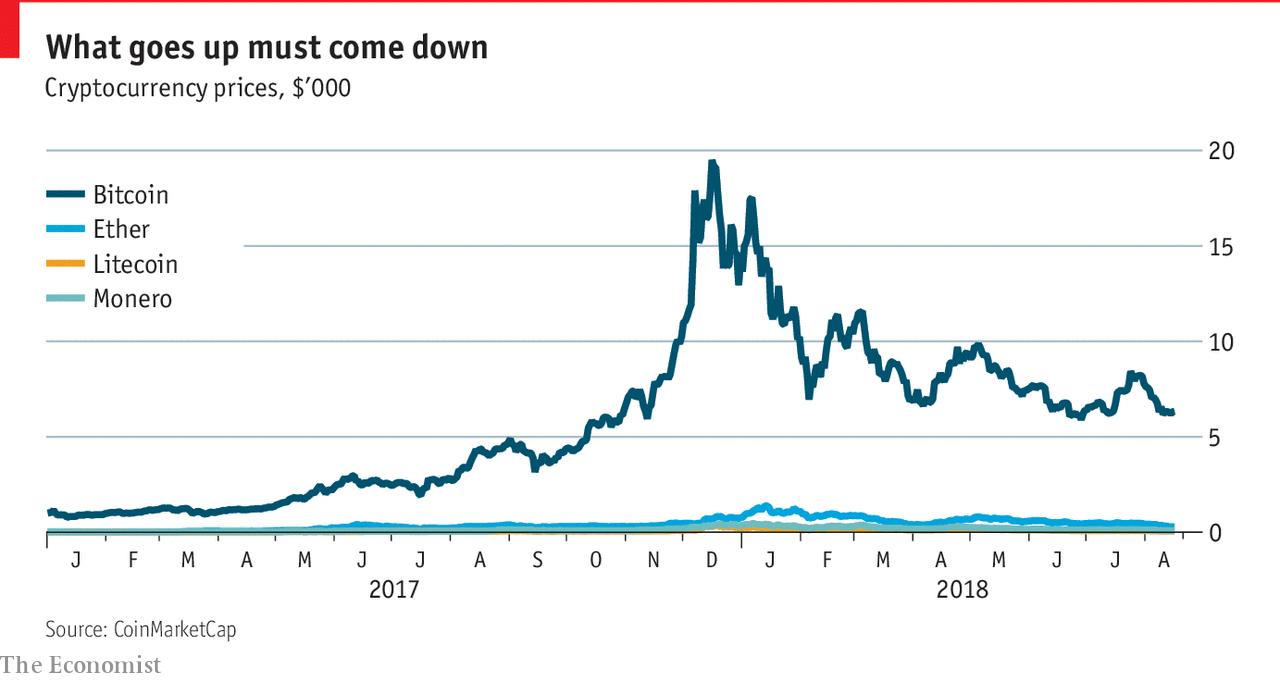

THE PRICE chart at CoinDesk, a cryptocurrency news site, begins on July 18th 2010, when a bitcoin could be had for $0.09. By November 2013 it had reached $1,124. In the summer of 2017 it started to take off, reaching over $19,000 in December. By end-March 2018 it was back down below $7,000 and in late August it was hovering between $6,400 and $6,500 (see chart). That has made a few people very rich (just 100 accounts own 19% of all existing bitcoin), encouraged others to play for quick gains and left some nursing substantial losses.

Bitcoin was never meant to be an object of speculation. When the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto published a short paper outlining his plan for bitcoin a decade ago, it was as a political project. Bitcoin’s roots lie in the “cypherpunk” movement, a philosophy that combines an anarchic dislike of governments and large companies with the techno-Utopian belief that computers and cryptography can liberate and protect people. Much of the early development of the internet was informed by similar ideas.

Bitcoin was intended as a computerised version of cash or gold, a “censorship-resistant” alternative to online payment systems run by companies such as Visa and PayPal. If trust in a central authority could be replaced with trust in computer code and mathematics, users could cut out the middleman and deal directly with each other, rugged individualist to rugged individualist.

Electronic cash is not a new idea. In a paper published in 1982 David Chaum, a computer scientist, had suggested using cryptography to create electronic cash, and the cypherpunks had been kicking such ideas around since the late 1990s. What made Mr Nakamoto’s invention stand out was that he had found a solution to one of the biggest problems with computerised money—how to keep users from spending the same digital coin repeatedly without relying on a trusted authority to check every transaction.

With a physical currency, this problem mostly takes care of itself. Once a coin or note has been handed over, its original owner can no longer spend it. But digital currencies are just wisps of information on a computer, and computers are designed to move and copy information easily. Mr Nakamoto solved the problem by handing the job of policing the system to its users. Bitcoin is designed to generate a permanent, constantly growing list of every transaction ever performed with the currency—the “blockchain”. Since all users have a copy of the system’s records, they would spot attempts to spend the same bitcoin twice.

A centralised institution like a bank can simply update its internal records every time its customers perform a transaction. Since bitcoin is decentralised, though, all transactions must be broadcast to everyone on the network so that they can update their local copies of the blockchain. When two parties want to make a transaction, they alert everyone else of their intention. Those proposed transactions are bundled into blocks by a subset of users called “miners”, whose job is to maintain the records and ensure their integrity. Every block is connected to its predecessor by a chain of cryptographic links, which makes it next to impossible to alter records once finalised.

In order to prevent malicious miners from subverting that process, bitcoin requires something called “proof of work”, in which miners demonstrate their commitment by competing to crack mathematical problems that are hard to solve but whose solutions are easy to check. Only the winner of each competition is allowed to add a block to the chain. The network aims for an average block-generation rate of one every ten minutes. If blocks come in faster than this, mining is made harder to slow things down.

All that computation takes a lot of electricity, and hence money (see article), so each new block earns its miner a reward, starting off at 50 bitcoin in 2009 and programmed to halve every four years. It is currently 12.5 bitcoin, or around $80,000. These block rewards are the only source of new bitcoin in the system. Mr Nakamoto argued that central banks cannot be trusted not to debase their currencies by printing money, so he set a hard limit of 21m for the number of bitcoin that could ever be mined.

All this may sound complicated, but the system generally works. Bitcoin can be used to make payments between any two users of the software, and though the experience is not exactly like using cash, it is a reasonable electronic analogue. Even so, bitcoin has failed to become an established currency, let alone—as its more ideological supporters had hoped—to flourish as an alternative to the traditional financial system.

One reason is that it is still not user-friendly. All participants have to download specialist software, and getting traditional money into and out of bitcoin’s ecosystem is fiddly. Moreover, although the lack of a central authority makes the system resilient to attempts at coercion, it also means that if something goes wrong, there is no one who can fix it.

The original idea was that bitcoin users would “be their own banks”, responsible for the security of their own funds, says David Gerard, a cryptocurrency-watcher and systems administrator. But that is harder than it sounds. If you lose access to your stash of bitcoin—say, by mislaying a USB stick or accidentally overwriting a hard drive—it can be impossible to recover. Many users therefore store their bitcoin on exchanges (companies that let users trade ordinary currency for the cryptographic sort). But many exchanges are amateurish operations and have an unenviable record of being hacked. And when bitcoins are stolen, there is no insurance scheme to make the owners whole. Nor are there any other protections of the sort that modern consumers take for granted. Mr Nakamoto’s original paper proudly points out that with bitcoin, chargebacks (used when a credit-card holder disputes a transaction) are impossible.

There are structural problems, too. The size of an individual block of transactions is fixed, and the network enforces an average block-generation rate of one every ten minutes. In practice, that limits bitcoin’s throughput to around seven transactions per second. (Visa’s payment network can manage tens of thousands.) So when demand for bitcoin transactions is high, the system clogs up. Users have to accept that their transactions may be delayed or not go through at all, or offer miners extra fees as an incentive to prioritise their payments. Mr Nakamoto had hoped that bitcoin’s transaction fees would settle at fractions of a cent, but at the height of the boom in late 2017 they briefly reached $55. They have since come down to about $0.65.

Faster, faster

Bitcoin’s developers have tried various tweaks and workarounds to ease the jam. A scheme called SegWit, first introduced in August 2017, has provided a little extra wiggle room. A more ambitious proposal, called the Lightning Network, hopes to take the bulk of transactions off the ponderous blockchain system and getting users to trade directly with each other, but after a couple of years in development it remains plagued by reliability problems. One recent evaluation by Diar, the cryptocurrency-research firm, found that Lightning transactions became increasingly less likely to be completed successfully as they got bigger.

Volatility, insecurity and occasional congestion make for a poor currency, so bitcoin has done best on the economic fringes. One use is for buying drugs and other dodgy items from online black markets, where buyers and sellers are prepared to put up with the downsides because they want to cover their tracks. It can help citizens of countries with currency controls get around them, says Alistair Milne, a financial economist at the University of Loughborough. And some cyber-criminals have turned to it for ransom demands.

Legitimate businesses, with a few exceptions, have proved more cautious. A report from JPMorgan published in 2017 found that, of the top 500 online retailers, only three accepted bitcoin, down from five the year before. Among those that have stopped supporting it are Expedia, a travel agency, and Valve, which runs Steam, an online video-games shop (which cited “high fees and volatility” as the reasons). Chainalysis, a research firm based in New York that tracks data from 17 different bitcoin merchant-payment processors, found that monthly transactions peaked in September 2017 at $411m, and had declined to $60m by May this year.

The South Sea bubble redux

The volatility that makes bitcoin unattractive as a currency also makes it an exciting target for speculation. “If we’re being honest,” says Tim Swanson, the founder of Post Oak Labs, a firm that provides technology advice, “the majority of people are buying [cryptocurrencies] because they hope the price will go up, rather than for any great philosophical reason.”

Condemnation from prominent figures has only added to the currency’s allure. Warren Buffett, a wealthy American investor, has called bitcoin “rat poison”. Jamie Dimon, the boss of JPMorgan—the sort of financial institution that bitcoin fans dislike—has described it as “a fraud”. A research note from Goldman Sachs, a bank, published in July, describes cryptocurrencies as “a mania” and concludes that they “garner far more…attention than is warranted”. Still, back in May the same bank announced its intention to open a cryptocurrency trading desk, citing demand from its customers. Autonomous Next, a financial-research firm, reckons that 175 cryptocurrency funds were set up in 2017, up from just 20 the year before.

Would-be punters will need a strong stomach. Bitcoin is thinly traded and barely regulated, and rumours of large-scale price manipulation have been supported by unusual trading patterns on exchanges. A paper published by two researchers at the University of Texas at Austin asks whether Tether, another cryptocurrency, is being used to prop up the price of bitcoin.

Governments are beginning to take notice. In May South Korean regulators raided Upbit, that country’s largest cryptocurrency exchange. In the same month America’s justice department began a criminal investigation into manipulation of bitcoin’s price.

Official scrutiny, and the recent drop in prices, have spooked many investors. Goldman Sachs argues that bitcoin remains overvalued. But for every bear there is a bull. Tim Draper, a venture capitalist who made his fortune backing technology companies, has forecast that by 2022 a bitcoin will be worth $250,000.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario