'Everybody Knew This Was Coming'

by: The Heisenberg

- Emerging markets have continued to melt down amid the crisis in Turkey and amid ongoing questions about the unwind of the carry trade in the face of Fed tightening.

- It's important to note that large asset allocators knew this was coming, but they had no choice but to contribute to the conditions that made it inevitable.

- There's nothing written in stone that says this has to spill over into U.S. stocks, but I think it's time for Jerome Powell to take a page out of Yellen's book.

- It's important to note that large asset allocators knew this was coming, but they had no choice but to contribute to the conditions that made it inevitable.

- There's nothing written in stone that says this has to spill over into U.S. stocks, but I think it's time for Jerome Powell to take a page out of Yellen's book.

Let's face it: virtually everybody knew this was coming. But in the frantic QE-inspired hunt for yield, nobody cared.

That's from the latest note penned by SocGen's Albert Edwards and he is of course talking about the ongoing trials and tribulations of emerging market assets (hereafter "EM" assets).

Albert's latest piece is longer than usual, and it has a kind of "where do I even start?" feel to it, which makes it similar in tone to a lot of the recent research on this subject. The overarching problem when it comes to writing for the institutional crowd and for professional investors more generally about the turmoil in EM is that with the possible exception of those who aren't old enough to understand the context, it's just an exercise in preaching to the choir. It's not that everyone was comfortable being herded into EM assets and various other carry trades, it's that increasingly, there was no choice.

Remember, when it comes to markets, "choice" and "selection" are two different things.

Deutsche Bank's Aleksandar Kocic talked about this at length back in January. By mid-2017, everything had converged one choice: harvest carry or go out of business, as AUM hits the exits thanks to underperformance. Here's how Citi's Hans Lorenzen put it in a note dated February 8, 2017:

Deutsche Bank's Aleksandar Kocic talked about this at length back in January. By mid-2017, everything had converged one choice: harvest carry or go out of business, as AUM hits the exits thanks to underperformance. Here's how Citi's Hans Lorenzen put it in a note dated February 8, 2017:

When spreads are low, volatility is low and dispersion is low, a few basis points of carry can matter a lot to a fund’s percentile performance against peers. And against the short-term metrics by which performance tends to be measured many will struggle to forego the incremental carry – until a negative trigger becomes immediately obvious.

And so, asset allocators didn't really have choice", per se. As Kocic put in January, "free choice" was replaced by "free selection" form a set of options. Those options were simply different ways of expressing the same trade. The only thing that separated one from the other was the amount of carry on offer. Citi's Matt King summed this up neatly last November, writing that "trades and strategies which explicitly or implicitly rely on the low-volatility environment continuing, are becoming more and more ubiquitous."

That dynamic is in no small part responsible for overcrowding in EM assets. If you think back to a post I published here on May 19, I suggested that Jerome Powell was either not entirely cognizant of the situation or, far more likely, simply playing it down in order to try and verbally reassure markets in the face of a persistently hawkish Fed. Here's what Powell said at an IMF/SNB event in early May:

Monetary stimulus by the Fed and other advanced economies played a relatively limited role in the surge of capital flows to (emerging market economies) in recent years.

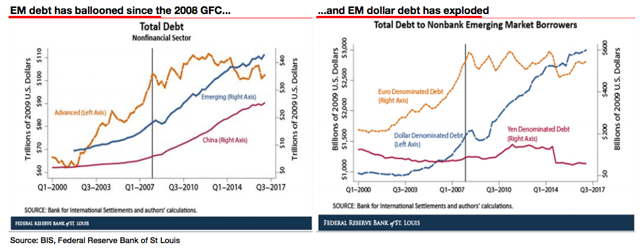

Obviously that isn't true. A charitable interpretation would be to say it's "mostly false". Here are some simple visuals:

Fed tightening is leading to a reversal of the dynamics described above. For instance, there are now actual "choices" again, with the quintessential example being USD cash. Here's what the above-mentioned Matt King wrote in a note dated Thursday:

The big trade during the years of QE and zero rates has been out of cash and into just about anything. Returns in 2018 are proving nothing like as good as in 2017.

Rising volatility and meagre YTD returns are suddenly being complemented by renewed awareness of how single-name blow-ups can at a stroke wipe out months of carry. That sucking sound is the irresistible lure of 2.5% on $ cash – risk-free – pulling money from your asset class.

It's important to remember the role that U.S. fiscal policy plays in that equation. I've written exhaustively on this. Late-cycle fiscal stimulus and the prospect of tariffs driving up consumer prices are contributing to the Fed's propensity to lean hawkish. At the same time, the deluge of Treasury supply necessitated by the tax cuts and spending bill is colliding with Fed balance sheet rundown to force private investors to absorb more U.S. debt. That sucks liquidity out of the rest of the USD bond market. Just about the last thing you want, given the setup illustrated in the right pane shown above, is a dearth of liquidity in the USD bond market.

This setup would already be conducive to an unwind in the various carry trades that have proliferated in the post-crisis era and naturally, the weakest hands would be flushed out first.

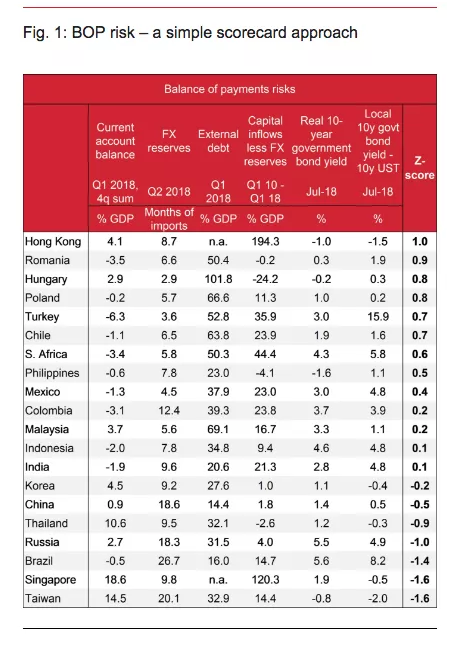

Turkey is one of the weakest hands from a fundamental standpoint (i.e., large current account deficit and large reliance on foreign currency debt), which is why it isn't surprising that it's one of the first dominos to fall. Below, find a handy scorecard and the accompanying instructions for reading it from Nomura.

To arrive at an overall summary measure for each country, we first convert the values for vulnerability indicators into standardized Z-scores. We then take a weighted average of the six Z-scores for each country (we assign higher weightings to the current account and FX reserves) to arrive at our overall summary statistic (final column in Figure 1). The higher the Z-score, the larger the BOP risk.

But again, asset allocators already knew this - all too well in fact, given that they were the ones who were forced into misallocating investor capital as developed market (hereafter "DM") central banks forced everyone down the quality ladder and out the risk curve.

That's what makes writing about this challenging if the audience is professional investors. If you're an analyst or a macro strategist, you have to talk about it because it's the only thing that matters in markets right now, but because asset allocators are fully apprised of what's going on by virtue of the fact that they were compelled to participate in creating the conditions for the unwind, reiterating the points is akin to rubbing it in. Here's Albert Edwards again from the same note cited here at the outset:

And this is always the problem while liquidity is washing through the financial markets because of loose money polices (usually centered around the Fed). Almost nobody is interested in heeding the pessimists and positioning of the inevitable financial market blow-up when eventually excessively loose monetary policy is belatedly tightened. Investors, drunk on the elixir of free money, think the good times will roll on forever. And even if they are cautious, a few quarters of underperformance usually invites either capitulation or being fired.

Albert has the luxury of being more blunt than most analysts, but that last point about being "fired", is just a more direct way of saying what Citi's Hans Lorenzen said in the 2017 note mentioned above and what Deutsche Bank's Aleksandar Kocic wrote in January when he said the "choice" between harvesting carry and going out of business isn't really much of a "choice."

But while everyone was well apprised of the inevitability of an unwind, what no one was quite prepared for was a scenario where that unwind would coincide with a series of geopolitical headwinds that have served to meaningfully exacerbate the situation and heighten the risk that the well telegraphed reversal of the carry trade will mushroom into something that turns systemic.

Those three geopolitical headwinds are as follows:

- the trade war

- the diplomatic row between the U.S. and Turkey and the concurrent power grab by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan

- the threat of sanctions on Russian sovereign debt

Without jumping too far down the rabbit hole on those three points, let me just add a bit of color on each.

The trade war threatens to undermine global growth and could weigh on the Chinese economy at a time when activity data is already decelerating. That's clearly negative for emerging markets as an asset class.

The diplomatic row between the U.S. and Turkey makes it potentially more challenging for Ankara to secure an IMF bailout (given Washington's sway over the institution) and also puts anyone who might otherwise be inclined to throw Turkey a lifeline in the awkward position of effectively undermining the U.S. at a time when the current administration is already at odds with most of the world on trade. Erdogan's move to install his son-in-law as economic czar and the concurrent decision to amend the central bank's articles of association to give himself more sway, mean the chances of an appropriately strong monetary policy response to the lira crisis are diminished.

The threat of U.S. sanctions on Russian sovereign debt (as proposed by U.S. Senators Lindsey Graham and Bob Menendez earlier this month) raises the specter of dramatically reduced non-resident participation in the OFZ market and a repeat of the rout in Russian assets that unfolded in April.

Those are all tail risks, and one of them has already come calling in the form of the collapse of the Turkish lira. A rout in the Russian ruble or a steep downturn in global growth would be highly destabilizing for EM given how concerned everyone already is about the space.

Allow me a brief tangent here in the interest of making a point about one of those tail risks.

Earlier this month, Citi ran a detailed simulation to try and predict where USD/RUB would trade in the event the Graham/Menendez bill gets traction on Capitol Hill. The bank's worst-case scenario was "about 70". The cross was at ~62.50 when Citi's analysis was published. As the Turkish lira plunged and the State Department imposed sanctions on Russia in connection with the the Skripal case, the ruble slid beyond 68.

People are always asking me for predictions and I'll oblige those folks here. If the U.S. sanctions Russian sovereign debt and the unfolding EM crisis doesn't abate before then (either due to a Fed pause, an IMF program for Turkey or a definitive break in the trade stalemate between the U.S. and China), the ruble will careen well beyond the "worst-case" scenario of ~70 and Russian assets more generally will come under more intense pressure than they did in April when the imposition of sanctions on Kremlin-aligned oligarchs led to a "Black Monday" for Russian equities.

Ok, panning back out to EM at the asset class level, you should note that the disconnect between U.S. stocks (SPY) is pretty dramatic. Here's the S&P versus EM stocks and EM FX:

(Heisenberg)

And the following visual is implied volatility on the JPMorgan EM FX index relative to implied volatility on the G7 FX index:

What you see in that visual is basically just carry trades blowing up.

There is of course nothing written in stone that says U.S. equities can't continue to ignore what's going on in EM, but I would gently suggest that it's unlikely. One of the last remaining pillars of support for U.S. stocks is buybacks, and while Goldman recently raised their estimate for repurchase authorizations in 2018 to a record $1 trillion, SocGen's Andrew Lapthorne questioned not only the assumption that those announcements will actually manifest themselves in executions, but also the relative wisdom of the whole endeavor in a late-cycle environment.

Here's Andrew, from a note dated August 13:

Here's Andrew, from a note dated August 13:

We have written before on how announcing a buyback, but not actually carrying through with the buyback, has empirically been the best course of action for a company. So, seeing a high level of buyback announcements makes sense. What does not make sense is to assume that in the long-term this will be good for US equities. Yes, the overall pay-out ratio is high when you add buybacks to dividend payments, but a large chunk of this increase is being funded by cash from the balance sheet and the selling of liquid investment. Net Debt is therefore on the rise.

None of the above should necessarily be construed as an overtly bearish call in the near term.

Rather, I would echo JPMorgan's Marko Kolanovic in suggesting that now is the time for Jerome Powell's Fed to take a pause. This is playing out a lot like it did in 2015 and I think it would be wise for Powell to try and learn something from Janet Yellen's caution in September three years ago when turmoil in EM prompted the FOMC to delay "liftoff".

Rather, I would echo JPMorgan's Marko Kolanovic in suggesting that now is the time for Jerome Powell's Fed to take a pause. This is playing out a lot like it did in 2015 and I think it would be wise for Powell to try and learn something from Janet Yellen's caution in September three years ago when turmoil in EM prompted the FOMC to delay "liftoff".

After all, if there's anyone who knows a thing or two about how to keep a rally going, it's Janet Yellen.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario