I'm Not The Bear You're Looking For

by: The Heisenberg

Summary

- In 2018, I've variously attempted to disabuse readers of the notion that I fall into the same category as other notable pessimists.

- Amusingly, that effort has coincided with the realization of a number of event risks that actually lend credence to the bear case.

- Nevertheless, I'm still going to try and present the most balanced macro take possible, even when the storm clouds are gathering.

- Here's an in-depth, cross-asset look at the environment as it stands right now.

- Amusingly, that effort has coincided with the realization of a number of event risks that actually lend credence to the bear case.

- Nevertheless, I'm still going to try and present the most balanced macro take possible, even when the storm clouds are gathering.

- Here's an in-depth, cross-asset look at the environment as it stands right now.

You can't make an omelette without breaking a few eggs, and in my case, "you" can't make an omelette period, because breakfast is something that's always eluded my rudimentary cooking skills (long-time Heisenberg readers know I can cook a mean NY Strip, though).

The figurative omelette I set out to make in 2018 involved disabusing readers of the idea that my musings and various missives somehow belong in the same category as those emanating from a handful of big name pessimists and doomsayers.

Initially, I didn't mind being branded a pessimist, although I would have really preferred "cynic". But the mischaracterizations started to grate a bit as the "brand" grew. Some time late last year, folks started to make direct comparisons between me and other specific bearish commentators. At that juncture, I decided to make a concerted effort to recalibrate reader expectations, mostly because I didn't want my personal site to become a haven for geopolitical conspiracy theorists.

I'm a trained political scientist and I come from a family of academics that dedicated their entire lives to teaching liberal arts at the graduate and undergraduate level. My formal training in finance and economics was borne out of necessity when I decided to break with family precedent by not becoming a college teacher.

But the finance bent never diminished my passion for political science and long before I adopted the pseudonym, my raison d'être revolved around the notion that geopolitics and markets are inextricably bound up with one another and you can't properly understand the latter without studying the former.

Political science is obviously not a so-called "hard" science, and neither is economics, economists' protestations notwithstanding. But there's a fine line between, on one hand, acknowledging the inherent absurdity in using the word "science" to describe the study of politics and, on the other, making a mockery of the entire endeavor by pushing wild conspiracy theories. Long story short, I was getting a lot of the latter in the comments section of my own site and that started to beget similarly far-fetched theories about central bank conspiracies.

Invariably, that rather toxic combination manifests itself in predictions of 75% market crashes, calls for gold soaring to $30,000 and other various shenanigans. I have no patience for that. It flies in the face of my respect for academic rigor.

So, I started to infuse explicit caveats in my writing designed to make it clear that I'm not the bear you're looking for. Perhaps the most concise example of that effort can be found in "Albert Edwards Returns From Yosemite, Disagrees With Other Notable Bear When It Comes To Forest Fires", but on this platform, my shift in strategy has probably been most evident in my rather effusive praise for Mario Draghi and in my recent critiques of Jerome Powell's "plain English" approach to Fed communication.

Rekindling the metaphor I employed here at the outset, some eggs were indeed broken on the way to making my omelette. A few readers were seemingly disillusioned to learn that while I'm no fan of the post-crisis monetary policy regime and the distortions it's created across assets, I am a fan of the artistry involved in the maintenance of that policy regime. Similarly, I'm not a believer in the notion that central bankers set out to exacerbate wealth inequality (remember, enacting policies that you know will come with undesirable consequences is something entirely different from choosing those policies because they will bring about those consequences). Nor do I subscribe to the idea that creative destruction (i.e., some kind of "once and for all" purge of misallocated capital that involves a global depression) is something that's feasible, let alone desirable. In short: the "great reset" isn't coming. So if that's the rationale behind your wall-safe stuffed with physical gold coins, you might want to rethink that asset allocation decision.

I lost some followers on my site once folks figured out that I'm actually in the business of providing halfway serious analysis and, more amusingly, I left some Heisenberg Twitter critics flummoxed when I delivered critiques of the people they were comparing me to that were far harsher than anything they were prepared to say publicly.

The irony in all of this, is that 2018 turned out not to be a great year when it comes to making a concerted effort to shake the "permabear" label.

Part of me reveled in the collapse of the short VIX ETPs and the extent to which the subsequent systematic de-risking (which saw CTAs and risk parity mechanically unwind somewhere between $200 and $300 billion worth of equity exposure) validated my long-held "doom loop" warnings. But another part of me felt a little bit bad about it because when I went back and read my posts about those products for this platform, I realized that I should have been a bit more explicit about the fact that what I was predicting was a near certainty (as opposed to a worst case scenario).

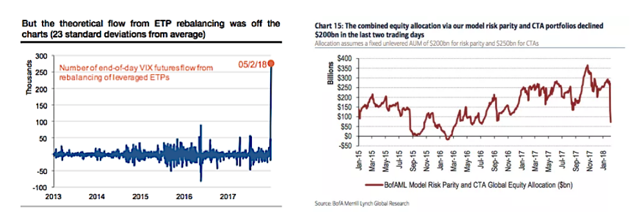

As a reminder, I repeatedly warned readers here that the levered and inverse VIX ETPs were accumulating a massive amount of rebalance risk that, if triggered, would mechanically involve panic-buying VIX futures into a volatility spike. On February 5, that rebalancing flow was a 23-standard-deviation event (charts below show the VIX ETP rebalancing flow on February 5, left pane, and the estimated combined de-risking in CTAs and risk parity strategies that occurred on Friday, February 2 and the following Monday).

(SocGen on the left, BofAML on the right)

While markets recovered from the February VIX quake, the newsflow since then has been unrelenting in terms of telegraphing event risk, whether it's trade wars, emerging market fragility, Italian political turmoil, regulatory risk in tech or domestic political friction in the United States. As I've tried to make clear in a number of recent posts, U.S. equities (SPY) are an island, of sorts. They are one of the only things that's still working.

So when it comes to timing, I could have picked a better six months when it comes to trying to convince people that I'm not a hopeless pessimist. That is, if you had to pick two six-month periods since the European debt crisis when it made sense to be a pessimist, one would be the second half of 2015 (following the yuan devaluation) and the other would be now. But that's how these things go. Markets have a penchant for making folks look silly; it's almost as if they (markets) are somehow capable of having a sense of purpose, despite being inanimate capital allocation mechanisms.

Recent surveys of institutional investors conducted by some of the major banks betray a sense of angst with regard to the growth outlook. To the extent large allocators of capital are worried, that consternation stems primarily from the prospect of trade tensions leading to a synchronous downturn in global growth. That said, most people seem to think the drag will be minimal, if not entirely inconsequential.

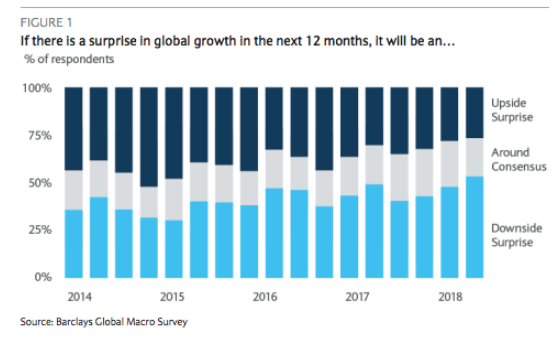

In their quarterly global macro survey, Barclays found that (and I'm quoting them here) “for the first time in at least four years, more than half of respondents think a disappointment [in global growth] lies ahead.”

(Barclays)

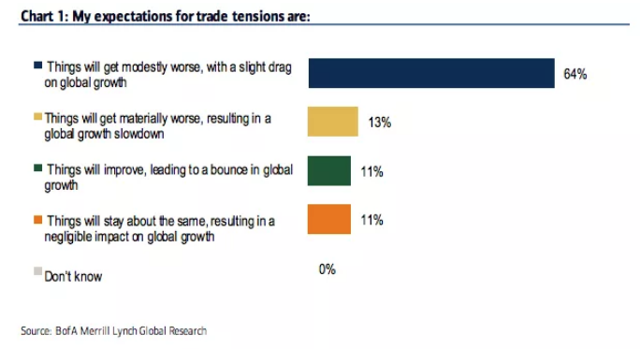

Similarly, in their latest rates and FX survey conducted on 06-11 July and representing the views of 58 fund managers responsible for $286 billion in AUM, BofAML found that 64% of respondents believe trade tensions are set to get “modestly worse” resulting in a drag on global growth.

(BofAML)

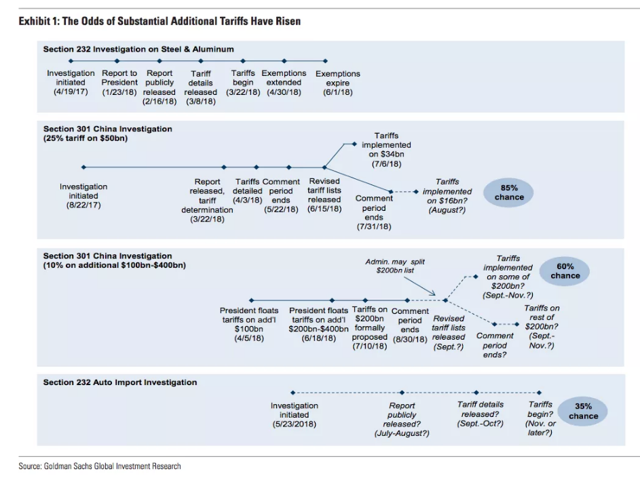

For their part, Goldman raised the odds of a material escalation in trade tensions between the U.S. and China to 60% in a note out Friday.

(Goldman)

Still, there's a demonstrable tendency for large investors (and analysts, for that matter) to doubt whether the trade tensions will ultimately morph into something that will be serious enough to catalyze a painful correction.

That relatively benign assessment is at odds with the consensus view on emerging markets (consensus is very cautious there) and the dour outlook for EM is part and parcel of the assumption that the Fed's near-term hawkishness will continue to exert pressure on developing market assets which have benefited in recent years from carry-inspired flows.

When it comes to the Fed, there's a sense that sooner or later, Jerome Powell will have to relent in the face of EM pressure and the prospect of trade tensions weighing on the growth outlook.

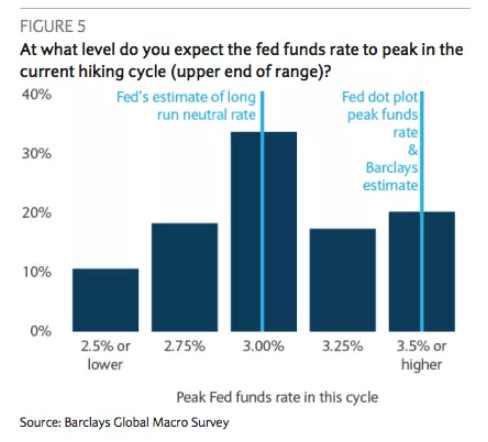

For instance, in the same BofAML survey cited above, nearly half of survey participants now expect the Fed’s balance sheet normalization push to conclude in 2019. In the Barclays poll, the bank notes that “despite [institutional investors'] apparent enthusiasm for all things American, survey respondents continue to question the Fed’s desire to tighten policy”. Here's the visual on that:

(Barclays)

All of this isn't entirely consistent. That is, it's difficult to reconcile the contention that trade frictions don't pose a meaningful threat to global growth with the notion that the Fed will have to end normalization "early" (and "early" is of course a relative term in that context).

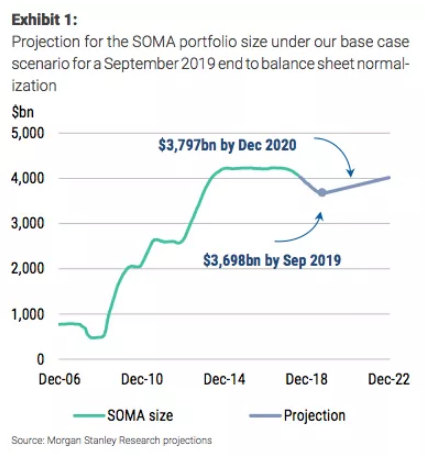

It's possible to couch the argument about an early end to Fed balance sheet normalization in technical terms. This week, Morgan Stanley was out with a great note in which they suggest that too much balance sheet normalization risks driving the effective federal funds rate above the rate paid on excess reserves, an outcome which increases the chances that EFFR rises above the target range. This is an in-depth, technical discussion (the note is a full 77 pages long), and if you want the longer treatment, you can find more here. But for our purposes, suffice to say that simply lowering IOER relative to the upper bound (as the Fed did this year) might not ultimately be sufficient to incentivize larger banks (where reserves are concentrated) to lend in the Fed funds market and so, if EFFR keeps bumping up against IOER after a theoretical second technical tweak, the Fed will ultimately be forced to end QT early in order to avoid a liquidity squeeze.

The "problem" (if that's what you want to call it) there is that depending on the mechanics, ending normalization early could end up inverting the curve. Here's an excerpt from the Morgan note:

The early end to balance sheet normalization means the Fed will begin rolling over more of its Treasury holdings sooner than we thought previously. We also think it means that the Fed will remove Treasury supply from the secondary market when it reinvests agency debt and MBS principal into the Treasury market instead of the agency MBS market. In turn, the US Treasury will have to issue fewer Treasuries to the public than what we thought before.

That means the burden on the private sector when it comes to absorbing the increased Treasury supply necessitated by Trump's deficit-funded fiscal stimulus will be lower. That, in turn, means less upward pressure on long-end yields and a flatter curve. The other implication there is that the Fed's balance sheet will actually begin to grow again in 2020. Here's a visual:

(Morgan Stanley)

The implications of this for risk assets are ambiguous. On one hand, an early end to balance sheet normalization and an effective resumption of QE in 2020 should be supportive, but in the meantime, it's a different story. For what it's worth, here's what Morgan Stanley says in the same note:

A larger Fed balance sheet may eventually be supportive for risky assets, but we expect the flow effects of normalization to hurt into 2019. We don’t think support will arrive until the balance sheet stops shrinking. We see the flow effects of balance sheet normalization, which should accelerate into 4Q18 and 1Q19, negatively affecting US corporate credit and equities (in a continuation of the rolling bear market). We think agency MBS should suffer from reduced demand into a bull flattener, but actual performance will depend on how agency MBS paydowns are reinvested. On a 12-month horizon, we suggest investors overweight US Treasuries, underweight US corporate credit, be neutral agency MBS versus Treasuries and overweight agency MBS relative to credit.

Try and stay with me here. The point of walking you through the Morgan Stanley projections is to underscore the extent to which investors and analysts doubt, for one reason or another, the Fed's ability to normalize policy. Those doubts, irrespective of what informs them, seem to be at odds with the relatively benign outlook for how severely the trade tension will affect global growth.

Trade tensions are hardly the only thing the Fed has to be concerned about. In a note out earlier this month, Credit Suisse suggested that rather than counting the number of months since the last downturn or trying to discern what patterns existed prior to previous post-War recessions, you might want to look at balance sheets, if it's canaries you seek. To wit, from the note (the reference to "this era" refers to post-1982 cycles):

This era has also seen rapid secular debt growth, an increase in market based financial intermediation, high derivatives use, and large capital flows. The era’s two biggest recessions – 2008 and 1991 – involved deleveraging, credit crises, and messy bankruptcies of financial and non-financial firms. In our view, the causal relationship between those balance sheet problems and recessions runs both ways, with those recessions intensifying when balance sheet dynamics weakened by a slowdown started to constrain behavior which then worsened activity further.

The bank's subsequent assessment of balance sheet health in the U.S. is, well, balanced (pardon the bad pun). On the bright side, they note that looking at gross leverage can be misleading (net debt is sitting near its three-decade average), maturity profiles have been extended (thanks in no small part to post-crisis monetary policy) and the stock of liquid assets on corporate balance sheets is now sufficient to cover more than half of short-term liabilities (if you're not up on such things, that is very high historically).

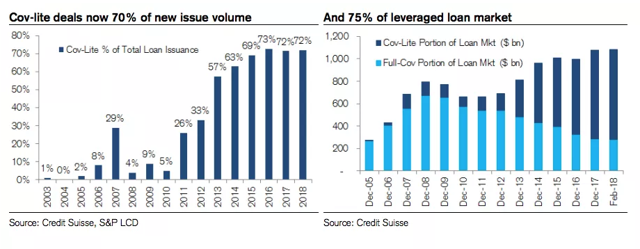

That said, there are problems. Notably, the desperate hunt for yield combined with the newfound threat of rising rates has catalyzed voracious demand for CLOs. That demand is at least in part responsible for a rather disconcerting trend in the market that's seen covenant-lite deals comprising a larger and larger share of new supply, which has in turn left three quarters of the leveraged loan market cov-lite.

That's all fine and good unless interest costs rise so far, so fast that issuers can't keep up, in which case things can get ugly very quick.

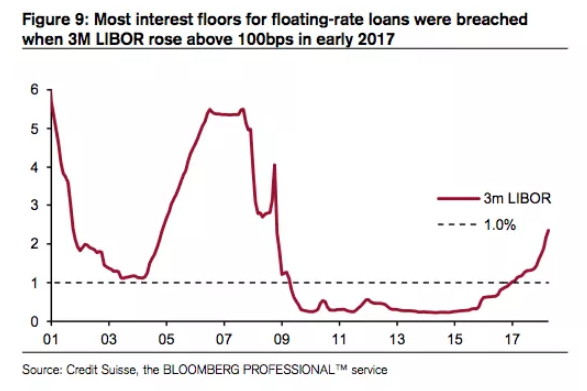

The Fed is surely aware of that scenario. While we're on this subject, do note that the Q1 dollar funding squeeze, which was precipitated by the knock-on effects of the tax cuts and the spending bill (e.g., repatriation effects and T-bill supply), breached the floors for floating rate borrowers.

(Credit Suisse)

(Credit Suisse)

This is where I get to refer you back to an all-time Heisenberg classic post called "'FRYBOR': Conversing With Drunk Albanians".

All in all, there seems to be a bit of cognitive dissonance within both the buyside and sellside communities when it comes to positing, on the one hand, a benign scenario wherein strong U.S. earnings, a robust U.S. economy and a reasonably favorable resolution to the trade tensions allow everything to proceed apace and, on the other, a Fed that won't ultimately be able to complete the normalization of policy due to a variety of concerns ranging from technical problems (see the above discussion from Morgan Stanley) to the possibility that the trade war mushrooms into something that represents a threat to global growth.

Generally speaking, I'm inclined to believe that the benign scenario is far-fetched at this point, if for no other reason than the fact that the "synchronous global growth" narrative that defined 2017 has morphed into a U.S.-centric story that implicitly assumes this expansion will end up being the longest in recorded history. I'm not sure that is a safe assumption.

When you throw in the fact that the Fed is effectively hamstrung in its ability to respond quickly by the necessity of guarding against a scenario where the combination of late-cycle fiscal stimulus and tariff-driven price increases spurs an acceleration in domestic inflation, you've got a less-than-ideal setup.

Coming full circle, I'm not keen on pushing an overtly bearish narrative just for the sake of being pessimistic. But I am keen on conducting a rigorous examination of the underlying dynamics at play both in markets and on the geopolitical scene. The above represents just such an examination.

In short, I'm not the bear you're looking for. But I'll be him today.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario