Bond Markets

Inflation

Interest Rates

Investment Strategies

Jerome Powell

Stock Markets

Treasury Bills

Treasury Yield Curve

SEAT BELTS FASTENED: VOLATILITY AHEAD / BARRON MAGAZINE´S COVER

Barron's Cover

Seat Belts Fastened: Volatility Ahead

By Vito J. Racanelli

Illustration: Illo: Alvaro Dominguez

For 15 months, from the 2016 election of President Donald Trump until recently, the stock market was a smooth, one-way trade: up 34%, with nary a significant pullback. A turn on the Brooklyn Cyclone it was not.

“Investors were in love with the economy, earnings growth, and the tax bill,” says Bob Doll, the chief equity strategist at Nuveen Asset Management. “It was a beautiful thing.”

That beautiful ride is now over.

A fast and vertiginous drop in February points to a material change in investor psychology, to cautious from enthusiastic. Where previously rising interest rates were acceptable because of strong global growth, now investors are focused on the potential inflationary threat from such growth.

The underlying concern is that rising prices could cause the Federal Reserve to tighten monetary policy faster than the market is anticipating. There is also a new unknown factor: Fed chair Jerome Powell, who was sworn in Feb. 5.

“Easy money created a safety net for stocks,” says Ernest Cecilia, chief investment officer at Bryn Mawr Trust. “That long period of time has certainly changed.”

The road ahead isn’t yet clear, and there are reasons to think the bull can continue to run. This time, however, trading is expected to be choppier, and investors more nervous than they have been for two years.

“It will be a tug of war,” says Keith Lerner, the chief market strategist at SunTrust Advisory Services, “a battle between fear and greed…Those who missed out want to get in, but those sitting on gains will want to sell,” he says.

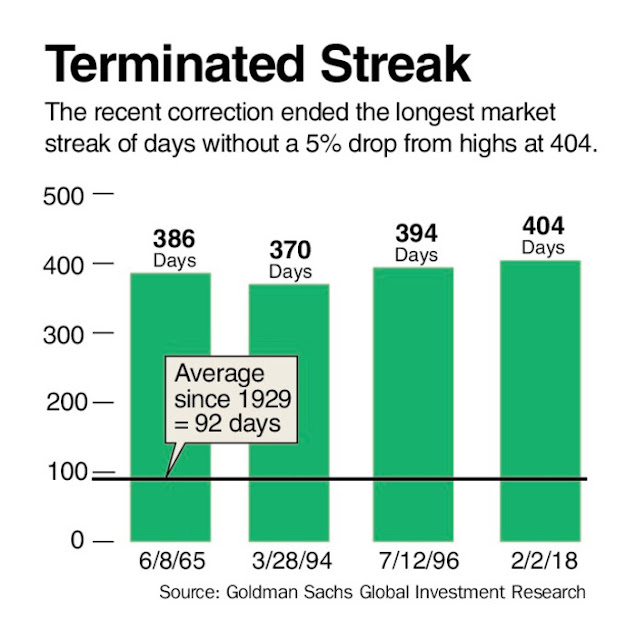

With February’s swift stock market correction, volatility has arrived and will probably stay awhile. The downturn last week ended a streak of 404 trading days without a 5% drop in stock prices from the previous high—the longest such streak in market history.

The last correction came in February 2016, when stocks dropped 15%. Investors then fretted that Chinese economic growth might be slowing, which turned out to be a false alarm. Long term, the latest nose dive might yet become just a bull speed bump, but there’s already been plenty of pain.

The Standard & Poor’s 500 index closed on Friday at 2619.55, rallying 1.5% on the day, but down 5.2% for the week. At Thursday’s close, stocks were down more than 10% from their previous all-time high—the traditional definition of a correction—of 2873, set Jan. 26. Down 2% the market is already below the previous year end—a position it was never in during 2017.

The index briefly broke below its 200-day moving average on Friday, a negative sign, but immediately bounced higher and managed to close above the moving average.

Does this mean a bear is in sight after nearly a decade in hibernation? Bear markets, a 20% drop from the highs, are typically caused by recessions. Yet anxiety about further losses has intensified, despite little evidence of any economic contraction in the offing.

An upturn in stock market participation by individual investors—typically latecomers in a bull market—also concerns some veteran market watchers.

And some think that the market is in the process of altering its view on the relative merits of stocks versus bonds. The stock plunge is the symptom and the disease is that there’s been a fundamental sentiment shift about rising rates, says Michael O’Rourke, the chief market strategist at Jones Trading.

“For years, people have said stocks are cheaper than bonds, but now yields are going higher,” he says. “Bonds are getting cheaper and will compete with stocks.” (Bond prices move inversely to yields.) The key metric that stocks are cheaper than bonds will reprice, O’Rourke predicts.

On Friday, yields on the U.S. 10-year Treasury note finished at 2.83%, significantly higher than the 2.41% at year-end 2017. That yield surge in such a short period of time was faster than the stock market could handle, Nuveen’s Doll says. On Feb. 2, when the stock market correction began, the spark was news from the Department of Labor that January’s hourly wage rise was 2.9%, the biggest year-over-year rise since June 2009, when the last recession ended. That released the market’s inflation demons.

As yields approached 3% that day, a level not seen since 2014, “investors took that 2.9% wage number and ran with it,” Cecilia of Bryn Mawr Trust says.

As the market was being whipsawed, the Fed—heretofore seen as supporting riskier assets like stocks with former chair Janet Yellen’s accommodative stance for years—has abruptly become something of a question mark. Powell’s tenure began on the worst day of the correction so far. Markets aren’t familiar enough with him yet, though he’s been a Fed governor since May 2012.

THE MARKET IS TESTING the new chair, says Lerner of SunTrust. “People think he will continue Yellen’s gradual rise in rate policy, and this market drop suggests he will have to,” he says.

While Powell himself hasn’t commented yet, and perhaps won’t do so early on, other Fed officials last week did reiterate the central bank’s plan of raising rates gradually. Investors expect the Fed to increase the federal-funds rate by three moves of 0.25 percentage point, to 2.00 to 2.25% by year end. On Tuesday, James Bullard, the president of the St. Louis Fed and a member of the Federal Open Market Committee, said he didn’t think the strong U.S. labor market meant higher inflation was imminent.

As it stands, sentiment weakness is unlikely to kill the bull market, but it is a less favorable environment for equities short-term. If you had to pick the time when the market’s attitude changed, it would probably be when the Dow Jones Industrial Average gapped down some 800 points in the matter of about 10 minutes midafternoon last Monday. At one point, the Dow was down nearly 1,600 points, the largest intraday point drop in history. You could almost hear the gasp on Wall Street.

While much of the plunge was blamed on automated and machine trading, not all of it was. Once arguably too complacent about inflation, investors are now clearly affected by growing uncertainty about rising bond yields.

With investors so troubled by one number—the unexpectedly high 2.9% wage rise—it’s likely that each inflation-related data release from here on could be a potential flash point for another bout of turbulence, if the data indicate inflation is rising fast. The next one could be the report on January consumer prices, which comes out on Wednesday. Investors should get used to more volatility than has been the case for a long time.

For now, the inflationary fears seem overdone. Tim Ghriskey, chief investment strategist at Inverness Counsel, says runaway inflation would be a worry, “but we aren’t anywhere near that. I see no major reason for a spike in yields.”

The stock market decline is more a function of the sharp 7% January rise—at one point—than anything else, he adds. The drop smacked of a lack of rationality, where selling begets selling, he says.

Tom Elliott, international investment strategist for deVere Group, calls the yield rise an overreaction to inflation data.

“Herd mentality had stocks overreacting too—and ignoring the contradictions,” he says. Stronger economic growth (implied by the wage rise) is good for earnings, and equities—unlike bonds—are a hedge against inflation. “If you believe that bond yields are rising on inflation, that’s when you run to stocks,” he says.

Indeed, there are powerful fundamentals driving the bull higher. Stronger global synchronized economic growth along with the weaker dollar should help drive profits at many of the companies in the S&P 500. Last month, for example, the International Monetary Fund raised its estimate for global growth to 3.9% from 3.7%. Earnings per share—even before the recent tax changes—have risen at rates not seen for years.

If there is a silver lining to this correction, it is that stocks are much cheaper than they were just a few days ago. The S&P 500 index’s valuation has dropped sharply. S&P 500 earnings per share are expected to jump 17% in 2018, to $156.88 from an estimated $132.40 last year. In 2019, a further 10% rise to $172.67 is anticipated by analysts. Consequently, the market’s price/earnings ratio has dropped to 16.7 times forward earnings—the lowest since one year ago—from 18.8 times at January’s high.

Nuveen’s Doll expects the market P/E to be lower on Dec. 31 than it was on Jan. 1, which would be the first time in six years that the P/E declined in the course of the year, he adds. He looks for the S&P 500 index to finish around 2800 this year, for a total return of 6% to 7% when all is said and done.

Some bullish strategists suggest the correction is actually a positive long-term development for the bull market.

“It isn’t the beginning of the end, but a normal correction in a long upward move,” opines Chris Gaffney, president of world markets at EverBank. Rates are low, global growth is good, and earnings are better than expected, says Gaffney, who expects a choppy market with an upward bias. Interest rates are the biggest risk, but the Fed will raise gradually and a 3% yield on the 10-year Treasury isn’t the end of the world for stocks, though it could pressure dividend shares, he says.

WHAT MATTERS, says another bull, Jim McDonald, chief investment strategist at Northern Trust, isn’t the number of rate increases but the environment when they are raised. There have been instances in the past when a bull market didn’t blink at a Fed rate increase of three percentage points and another that was brought down by the same amount of hikes.

Moreover, he adds, mini-meltdowns like the one seen last week “will help extend the bull cycle,” he says. It restrains the stock market euphoria, something the Fed is likely to have concerns about, he adds.

McDonald isn’t fazed by the 2.9% wage number: “You need to see wage gains above 4% to see an impact on inflation.” There’s been a lot of media attention given to the wage boosts and bonuses seen at some big U.S. companies, but “we are making a bet that in general managements haven’t lost their cost discipline,” he says.

While market bulls remain uncowed in their enthusiasm, they also acknowledge the market wounds aren’t superficial, and that volatility isn’t going away soon. Bear markets are typically born of recessions and the evidence for that is slim, they say.

The caveat to the bullish view is, unsurprisingly, inflation. Jason Pride, director of investment strategy at Glenmede, says that if the Fed were to increase rates four or five times this year, instead of the expected three, it would pressure stock values. And exogenous geopolitical events could take on added meaning in the current environment, Pride says.

And here’s an interesting twist. A look at the CME Fed futures market shows that market’s view of a third rate increase in December has dropped to a 44% probability on Friday from nearly 58% on Jan. 26, the day the market hit its all-time high, according to Bloomberg. Fed futures have had a good track record of correctly predicting Fed rate changes over the past few years. The stock market’s selloff makes a third rate hike less certain, given the tightening in financial conditions from lower stock prices and higher bond yields.

Caveats are more important when the market’s valuation isn’t cheap on a historical basis, as is the case now. The higher the valuation, the lower the bar for risks and uncertainty that could elicit a market reaction. Before Feb. 2, few observers would have predicted a monthly wage increase would be the instigator of a correction.

INVESTOR WORRIES about inflation and yields are the paramount issues, but the destruction of investor complacency caused by February’s plunge might allow other back-burner issues—like the U.S. midterm elections in November or Chinese economic growth—to be viewed as more worrisome than they had been previously.

Ned Davis, senior investment strategist at Ned Davis Research Group, contends that when you get parabolic rises in stock prices—as in January—the market cracks can form more quickly. Easy monetary policy makes overvalued markets manageable. But when the Fed starts raising rates it can start to bite. Whether the next rally makes a new high or not is “very important,” Davis adds.

Previous to the correction, what was a positive development for Main Street—rising wages, low inflation, falling unemployment—was also promising for Wall Street. It meant, for example, that consumers enjoyed increasing income and with that a rising capacity to buy more of the things that Corporate America produced.

The turbulent reaction in the market, however, suggests the convergence of interests will be tested regularly this year.

“What might be good for Main Street, might not be good for Wall Street—if the Federal Reserve ends up tightening more quickly than investors expect,” SunTrust’s Lerner says.

One thing is clear: Interest rates are going up, not just in the U.S. but around the world. Although investors were well aware of this for over 12 months, it began to hurt only recently. From here on in, it is likely to become a bumpier market, with pockets of downdrafts—perhaps like the one that kicked off this month, perhaps even worse—before the bull resumes.

The threat of a bear market remains relatively low, but the one-way ride is over.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario