LITTLE INTEREST: AMERICAN BANKS PAY DEPOSITORS LESS THAN ONLINE ACCOUNTS / THE ECONOMIST

Little interest

American banks pay depositors less than online accounts

They seem to be relying on the power of inertia to retain their customers—a risky strategy

EVERYONE knows that interest rates are rising—except, perhaps, one group: American savers who have put $12trn in bank accounts. They have seen the government’s deposit guarantee, purportedly designed to protect them, become a ticket for banks to receive free money. For evidence, look no further than the ubiquitous bank branches dotting America’s high streets.

Those seeking a home for their money find that, unlike petrol stations or grocers, banks are not required to post their most important price, the interest rate. Ask and you will be referred to a specialised member of staff. After a wait, numbers are typed into a computer, followed by pauses for thought, a bit of throat clearing and, often, comments that the current rates on offer may not exceed inflation. Then come hints, doubtless filtered through a compliance department, of the higher returns available on the bank’s investment offerings, which, of course, carry risks (and fees).

Only then is the diligent customer told the rates on offer, ranging from almost nothing to almost nothing at all. A knowledgeable saver might then ask about certificates of deposit, guaranteed securities with maturities of up to five years. Here too the banks’ offerings often carry meagre rates. The exception may be a promotional deal—a slightly higher rate with an expiry date, intended to draw in new customers.

The high levels of deposits the big banks are sitting on suggest that many give up at this point, despairing of earning any return on their money. They would be wrong, however. Should they look online, at, for example, Bankrate.com, a common reference point, they would find lists of rates provided nationally on deposits (up to 1.6% per year) and certificates of deposits (3%). These rates have been rising, in line with the broader bond markets.

You would expect the gap between what is offered to savers in banks and what can be earned online and in the money markets to close. Not so. In 2014 Gary Zimmerman launched a web-based financial link, MaxMyInterest.com, that enabled customers to transfer funds smoothly between their usual banks and higher-yielding online accounts (also government-guaranteed).

At the time, banks paid on average 0.11% on savings accounts. Online his clients could receive 0.87%. Since then, his online rates have risen to an average of 1.52%, compared with 0.09% paid to high-street bank depositors.

If banks bother to defend their low rates, it is to point to an expanding range of associated benefits that they offer: automated banking, bill payment, credit cards, an ability to consolidate all of this easily online, and so on. This has sparked debate about “deposit beta”, or how much of an interest-rate rise banks can afford not to pass on to savers (short answer: a lot).

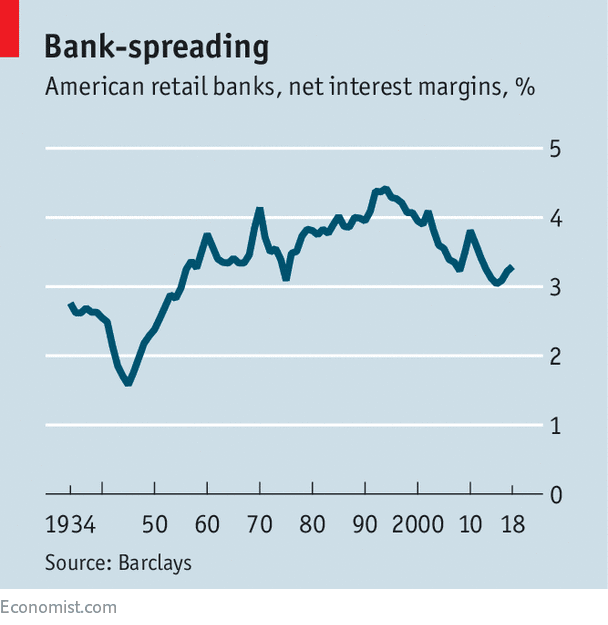

Jason Goldberg, an analyst at Barclays, has compiled data stretching back to 1934 on the spread between how much banks have to pay for money and what they receive (see chart).

After the financial crisis, low prevailing rates compressed this margin. But its recent widening has lasted unusually long—the first three-year streak since the 1970s is expected. And Mr Goldberg thinks more is to come as rate rises by the Federal Reserve continue to exceed what filters down to depositors. That will play a critical role in strong bank profits.

Given the upheaval and price-cutting that online shopping has brought to the rest of the retail world, this is at the very least odd, and seems unsustainable, were it not for the power of inertia. But relying on inertia is a dangerous strategy. At some so far undiscovered tipping-point, customers may wake up abruptly, shift their money and never come back.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario