Et Voilà

By Grant Williams

In years to come, when financial historians look to pinpoint the precise moment in time when the excesses of Quantitative Easing reached their apex, I suspect that November 15th, 2017 may well be the date upon which they settle.

On that Wednesday, on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean, two events occurred which – once hindsight provides its inevitable clarity – will, I believe, provide the perfect crystallization of both the degree to which central bank-inspired asset price inflation has run amok and the utter folly of the negative interest rates inspired by those same academic assassins.

Were it possible to bring lawsuits against the men and women holding the highest financial offices in the world for financial malfeasance in an attempt to recover losses, then these two near-simultaneous events would be submitted as exhibits A and B in the biggest class action suit ever filed.

The image on the cover of this week’s edition of Things That Make You Go Hmmm... [Ed. note: reproduced above] is a clue to the event which transpired on the Western side of the Atlantic while the simple logo below provides everything you need to pinpoint the moment of madness at its eastern extremes.

Let’s begin in New York, shall we? At 20 Rockefeller Plaza to be precise.

On the evening of November 15th, the Christie’s Post-War & Contemporary Art Evening Sale attracted a bumper audience – largely due to Lot 9B, an oil on panel measuring 25 7/8 x 18 in. which was neither post-war (unless the wars in question were the Wars of the Roses or the Albanian–Venetian War), nor was it particularly ‘contemporary’ (unless the contemporaries in question included Ludovico il Moro Sforza (the Duke of Milan), or Sandro Botticelli).

The oil on panel in question had found its way into the British Royal Family’s personal collection by way of marriage when Queen Henrietty of France married Charles I in 1625, and there it stayed for almost 150 years until, in 1763, the painting went missing.

It didn’t surface until the late 19th century when it appeared in the private collection of Sir Frederick Cook, an expatriate English nobleman living in the great state of Virginia, USA.

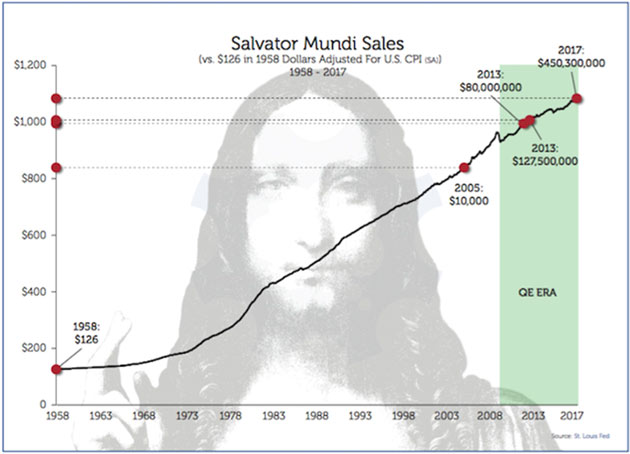

n 1958, the painting was auctioned by Sotheby’s for £45 ($126) and sold to someone identified only as “Kuntz”. In the sale brochure, the artist credited with creating the near-$150 painting at that time was Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, a young painter from Lombardy who worked in the studio of Leonardo da Vinci.

The painting was then not seen again for over half a century until, at an estate sale in 2005, a New York art dealer named Alexander Parish purchased it for $10,000 and, while it is essentially impossible to adjust the painting’s value for inflation going back to1625, we can do so to 1958 with considerable ease.

In 2005, the $126 paid for the painting 47 years prior was worth $851.28 in inflation-adjusted dollars so the $10,000 price tag shows just how well the painting had kept its value in the intervening years. However, all this happened before 2008.

Before ZIRP.

Before QE.

Once we enter the Twilight Zone of extreme monetary policy experimentation, things start to get really wacky.

Parish and a consortium of fellow dealers including Sheldon Adelson and Robert Simon ‘authenticated’ the painting as a genuine Leonardo and, in 2013, they sold it to Yves Bouvier, the Freeport King, for an astonishing $80 million.

At this point in the proceedings, I feel it important to point out that $10,000 in 2005 dollars adjusted for inflation to 2013 equates to $11,928.

What happened next was even more mind-boggling as Bouvier then immediately re-sold the painting to Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev (the owner of AS Monaco) for...wait for it...$127.5 million.

Aaaaaaand just to remind you of those numbers again:

The painting sold for $80 million and $127.5 million IN THE SAME YEAR.

It’s almost as if people couldn’t get rid of their fiat currency fast enough. We should all thank our lucky stars that there’s no inflation.

Rybolovlev purchased Salvator Mundi as part of a $2.1 billion collection of some 37 pieces which Bouvier put together for him but, when word of the gigantic markup Bouvier had made on the Leonardo, reached the oligarch’s ears, he filed both civil and criminal suits against Bouvier in both Monaco and Singapore claiming fraud and accusing Bouvier’s consortium of ‘significantly overcharging him’.

Source: St. Louis Fed

In the build-up to the sale, the chattering classes were focusing on whether or not Rybolovlev would be forced to take a nasty haircut on the supposedly inflated price he’d paid four years prior for the Leonardo:

(Al Jazeera): A Russian billionaire believes he was swindled when he bought it for $127.5 million. This week he will find out if he was right...

The auction house, which declines to comment on the controversy and identifies the seller only as a European collector, has valued it at $100 million.

Going into the auction, Christie’s certainly seemed to take the ‘under’ with their valuation and speculation ahead of the sale centred almost exclusively around validation rather than any great expectation of a headline-grabbing price being achieved.

...the price will be closely watched -- not just as one of fewer than 20 paintings by Da a’s hand accepted to exist, but by its owner, Dmitry Rybolovlev, the boss of football club AS Monaco who is suing Swiss art dealer Yves Bouvier in the city-state Hof Singapore].

Rybolovlev accuses Bouvier of conning him out of hundreds of millions of dollars, in parting with an eye-watering $2.1bn on 37 masterpieces. One of those works was “Salvator Mundi” which has been exhibited at The National Gallery in London.

Bouvier bought the Leonardo at Sotheby’s for $80 million in 2013. He resold it to the Russian tycoon for $127.5 million.

Despite its rarity (Salvator Mundi remains the only Leonardo in private hands – all his other known works are held in institutional collections or museums), the expected sale price was well short of the record for a piece of art sold at auction which had been fetched through the sale of Pablo Picasso’s The Women of Algiers (Version O) for $179.4 million in 2015.

When the auctioneer’s gavel came crashing down to cheers and thunderous applause after an electric bidding process (you can put yourself in the room by clicking here), the old record had been shattered as the formerly disputed Leonardo, which had been the subject of a multi-million dollar lawsuit over fraudulent over-charging, changed hands once again... this time for a little shy of half a billion dollars.

That’s right. With fees, Lot 9B sold for $450.3 million as an anonymous collector took the decision to exchange a pile of fiat currency for a real asset which has clearly more than held its value in the five centuries since its creation. His last bid increase of $30 million (when the price had been climbing in $1 million and $2 million increments), was both shocking and highly illustrative of my point.

Presumably the lawsuit against Bouvier will now be withdrawn, but these oligarchs have a habit of not letting go once they’ve sunk their teeth into something.

Incredibly, the $450 million dollars was handed over despite an enormous amount of debate as to the authenticity of Salvator Mundi (call me old fashioned, but if I’m going to drop half a billion on something, I’m gonna want to know it’s real):

(Bloomberg): Even before Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi went to auction Wednesday night at Christie’s in New York, naysayers from around the art world were savaging its authenticity. Various advisers were muttering darkly, both online and in the auction previews. A day before the sale, New York magazine’s Jerry Saltz wrote that though he’s “no art historian or any kind of expert in old masters,”just “one look at this painting tells me it’s no Leonardo.”

And that was before the painting obliterated every previous auction record, selling, with premium, for $450 million.

Shortly after the gavel came down, the New York Times published a piece by the critic Jason Farago wherein—after also noting that he’s “not the man to affirm or reject its attribution”—he declared that the painting is “a proficient but not especially distinguished religious picture from turn-of-the-16th-century Lombardy, put through a wringer of restorations.”

Had the buyer of the most expensive painting in the world just purchased a piece of junk?

“All of the most relevant people believe it’s by Leonardo, so the rather extensive criticism that goes ‘I don’t know anything about old masters, but I don’t think it’s by Leonardo’ shouldn’t ever have gone to print,” says British old masters dealer Charles Beddington. “Yes, it’s a picture that needed to be extensively restored.

But the fact that it’s unanimously accepted as a Leonardo shows it’s in good enough condition that there weren’t questions of authenticity.”

On a visit to preview the sale, noted art critic and host of the Viceland series ‘Most Expensivest’, the rapper 2 Chainz offered his thoughts on the Leonardo:

(NY Timez): Wearing a black Supreme hoodie, red-and-white track pants, white Balenciaga sneakers and maybe five pounds of gold chains, 2 Chainz rolled into the auction house a few minutes after 4pm on a windy Tuesday with a crew that included a stylist, a personal photographer, a publicist and a bodyguard.

He moved through Christie’s with the eager, excitable air of a dutiful student, fist-pounding and taking selfies with security guards. He respected fine art but knew little about it.

Chainz was shown Andy Warhol’s Sixty Last Suppers (a composition of 60 black-and-white silk screen interpretations of Leonardo’s iconic painting which was valued at $50 million and ended up selling for $60.87 million) and offered a critique:

“This is the best thing I’ve ever seen in my life,” said 2 Chainz, temporarily struggling for words as he gazed at the gargantuan piece of art. “This makes me want to be a billionaire. Can you imagine having this over your dining room table? Oh my God. You’d have to have the longest dining room table in history.”

Finally though, Chainz could stand it no longer. With the preview’s 5pm closing time rapidly approaching, enough was enough:

“Take me to the big one,” he said, referring to the work that Christie’s has called ‘The Last da Vinci’.

A line of about 100 people were still waiting to catch a glimpse of the rare painting by the Italian master, but Ms. Celis led 2 Chainz again through a back door to view it without waiting.

“Oh my God. $100 million,” 2 Chainz said, referring to the estimated value and shaking his head in disbelief as he gazed upon the revered painting of Christ...

A crowd of roughly 20 people still hovered around Salvator Mundi, but with Christie’s set to close in ten minutes, security guards informed everyone it was time to leave...

Before he left, however, Chainz had one question he wanted to ask his guide:

Being a keen arbiter of luxury, 2 Chainz remained skeptical of the painting’s worth.

“So,” he said turning to face Ms. Celis. “Tell me one more time, how do we know it’s not a copy of a copy?”

Copy or not, away from the Leonardo, there was a wealth of other post-war and contemporary art for sale and, wherever you looked, the prices being paid were not so much indicative of a catalogue stuffed to the gills with priceless treasures, but more of a group of potential buyers flush with cash and in a desperate hurry to get rid of their paper dollars and exchange them for something more tangible, lest the value of those paper dollars be debauched further by the monetary mandarins atop the financial totem pole. (In all, a total of almost $800 million was paid over the course of the evening.).

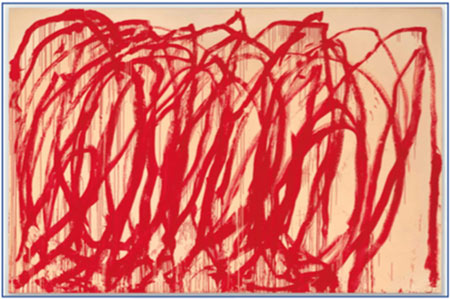

Lot 15B, a painting of vermilion spirals by the British artist Cy Twombly (below), painted just 12 years ago (how’s THAT for contemporary?) with a brush tied to the end of a pole fetched $46 million and Fernand Leger’s Contrastes de Formes sold for $60 million.

Source: Cy Twombly

In short, New York’s auction houses were the scene of a fiat feeding frenzy and, if you are paying close enough attention, it isn’t the only one of its kind.

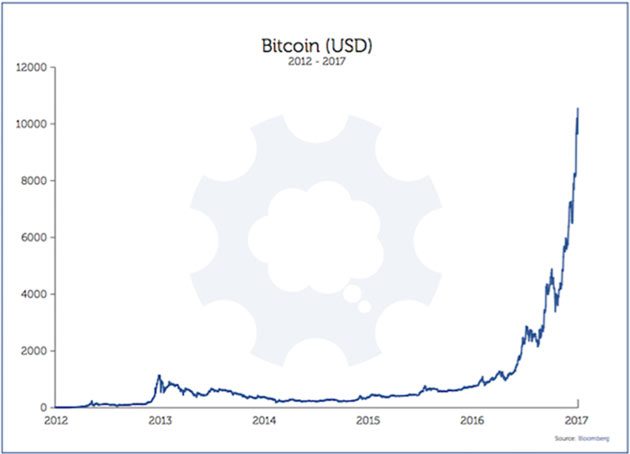

Just this week, bitcoin passed the $9,000 $10,000 $11,000 mark and, while there is undoubtedly real value in both the coins and the underlying blockchain technology, to say that currently the price is anything but a bubble is to fail to acknowledge a chart pattern which is familiar throughout financial history and clearly recognizable as a bubble (see chart below. Yes, that last gap up is essentially a vertical line).

Source: Bloomberg

Bitcoin now has a market cap of ~$200 billion – the vast majority of which represents profits made in the last 12 months so it will be interesting to see what that chart looks like when more established markets reacquaint themselves with the idea of volatility.

I will write more about bitcoin in January as it is an absolutely fascinating topic worthy of its own edition of Things That Make You Go Hmmm... but for now, let’s leave its price chart as merely another indication of the madness which has been fomented in one way or another by monetary policy.

What both bitcoin and the price of fine art both do, however, is demonstrate beyond any doubt the fallacy which speaks to there being no inflation (or at the very least that inflation is difficult to generate).

Inflation (of the asset price variety at least) has been running rampant as those fortunate enough to be near the central bank spigot have been the beneficiaries of eight years and multiple trillions of dollars of monetary largesse. Those further down the financial food chain haven’t been nearly so fortunate.

Each successive throwaway comment delivered by a central banker explaining how he or she is ‘concerned about rising wealth inequality’ is as shameful as it is mendacious.

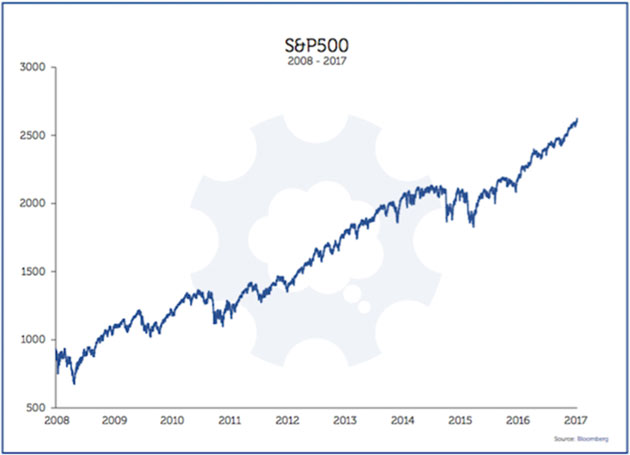

The sale of Salvator Mundi by Rybolovlev is just one example of the lunacy that central bank actions have created around asset prices (yes, equity markets like the S&P500 qualify) but the Russian is also no stranger to another asset class which has been blessed by the central banks – luxury real estate.

Source: Bloomberg

Until the duplex penthouse on the 89th and 90th floors of the One57 Tower on 57th street in Manhattan changed hands in January of 2015 for $100,471,452.77, Rybolovlev’s daughter, Ekaterina was the proud owner of the city’s most expensive home, having paid $88 million for the Central Park West penthouse of former Citigroup chairman Sandy Weill.

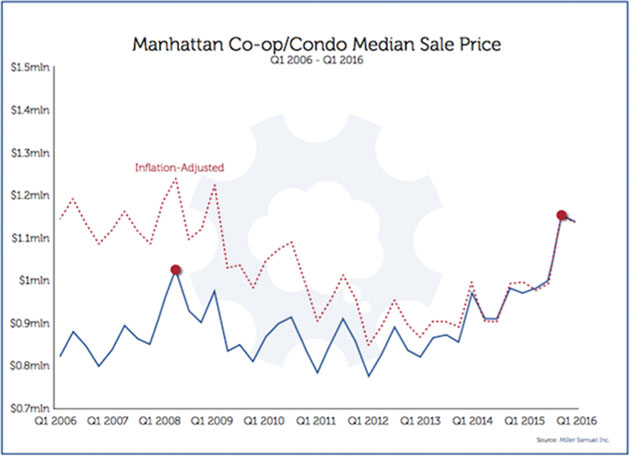

The charts of median sales prices in the Manhattan co-op and condo market (below) show precisely what has happened as the rich have gotten richer thanks to central bank policy over the last eight years.

Source: Miller Samuel Inc.

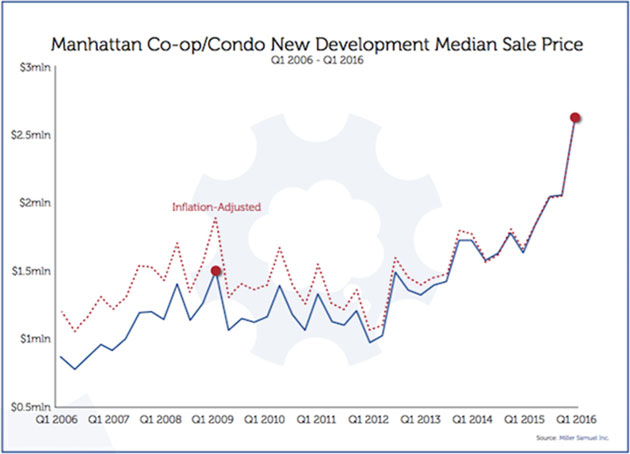

Source: Miller Samuel Inc.

The median sale price of a Manhattan co-op or condo has recovered nicely since the depths of the post-2008 fall but it remains below its inflation-adjusted high, set in (of course) mid-2008.

Meanwhile, if we take a look at new development prices we can see that virtually all the new co-op and condo development in Manhattan has been at the super luxury end of the market – designed specifically to cater to those who have been enriched beyond their wildest dreams over the last eight years and who need nice real assets into which they can swap their fiat gains.

I’ve said it before but it bears restating; the consistent narrative surrounding the curious absence of inflation is nothing more than a canard.

Whilst the CPI has remained (to central bankers at least) puzzlingly benign, the trillions in QE has ended up in the bank accounts of those who already had money and assets and the inflation in those areas has been astronomical.

This really isn’t something you need a PhD. in economics to figure out folks.

This asset price inflation somehow stays hidden in plain sight and all anybody seems to care about is headline inflation of the PCE / CPI variety – the very measure followed by the Fed when trying to achieve one half of their dual mandate.

However, there are signs of stirring in the inflationary cave which, unlike the whole ‘rising wealth inequality’ will have central bankers genuinely concerned.

But we’ll get back to those a little later on.

For now, we need to head East, across the Atlantic to that other event which occurred on November 15th.

The scene for this particular sign of the apex of the era of Quantitative Easing occurred, not in an auction room, but in the corporate finance department of Société Générale in Paris.

Soc Gen was the sole bookrunner of a €500 million 3-year senior unsecured zero coupon bond issue which was priced at 5 basis points over swap rates (the tightest ever issuance for 3-year corporate bond).

Fittingly, with rates at multi-century millennia lows, the company (whose executives I feel certain could hardly believe their luck when the book closed), dates back to the time of Napoléon. No, the other one.

I’m talking, for those of you who may have missed the press release on the cover of this week’s Things That Make You Go Hmmm..., about Veolia Environnement S.A.

We’ll get to the subject of that press release shortly but first, a little more useful history.

The story of Veolia Environnement S.A. is a remarkable tale which dates back to the times of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the first French Head of State to hold the title of President and, until the election of Emmanuel Macron in 2017, the youngest appointed to that office.

Bonaparte was the nephew and heir of Napoléon Bonaparte (yes, THAT Napoléon Bonaparte) and his term as President ran from 1848 until 1851 when, barred from seeking a second term by the country’s constitution, he orchestrated a coup d’état and took the title of Emperor on December 2, 1852 (the forty-eighth anniversary of his uncle’s coronation).

A year after ascending the throne Napoléon III (as he was known), issued an Imperial decree which established the Compagnie Générale des Eaux to provide water to the citizens of Lyon and, seven years later, it was granted a similar concession for the City of Paris.

All was well (pun intended) for ohhhh a little over a century as CGE focused its activities in the water sector but, with the 1970s came a new CEO, Guy Dejouany, and Guy had somewhat broader ambitions for the Company:

(Wikipedia): Beginning in 1980, CGE began diversifying its operations from water into waste management, energy, transport services, and construction and property. It acquired the “Compagnie Générale d’Entreprises Automobiles”(CGEA), specialized in industrial vehicles, which was later divided into two branches: Connex and Onyx Environnement. CGE then acquired the “Compagnie Générale de Chauffe”, and later the Montenay group. The Energy Services division these companies became part of was later (1998) renamed “Dalkia”.

CGE’s expansion into communication commenced with the establishment of Canal+ in 1983, the first Pay-TV channel in France. This expansion was accelerated after Jean-Marie Messier succeeded Guy Dejouany on 27 June 1996. In 1996, CGE created Cegetel to take advantage of the 1998 deregulation of the French telecommunications market, accelerating the move into the media sector which would culminate in the 2000 demerger into Vivendi Universal and Vivendi Environnement.

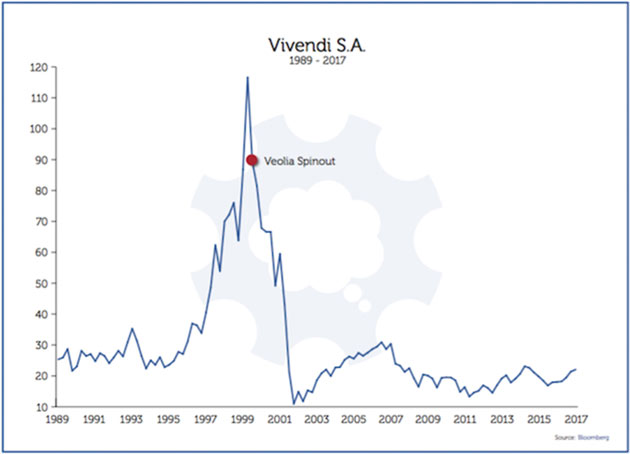

Yes, the water company founded during the Napoleonic era became media conglomerate Vivendi S.A. in 1998 and, two years later, in the midst of the dot-com bubble, the company spun off its core businesses (dahling, public utility companies were just sooooo 1850s) as Vivendi Environnement S.A., later renamed Veolia Environnement S.A., lest the hip, cool media group be somehow associated with water and waste management.

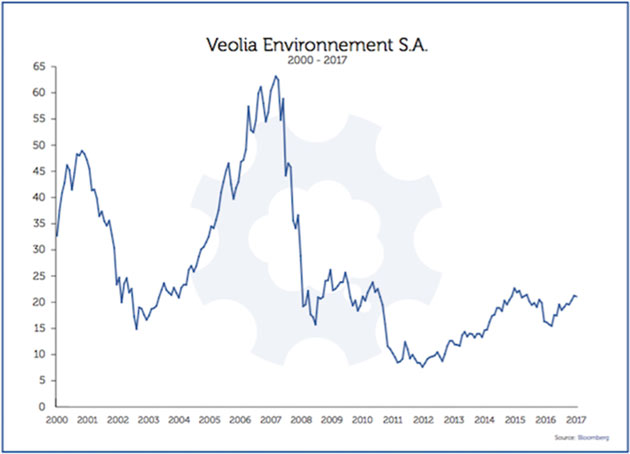

As you can see from the chart [below], Vivendi never quite recaptured its former glory and, while Veolia scaled new heights of its own before the next market peak in 2007, it too has taken a knee and is essentially refusing to budge from the canvas.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

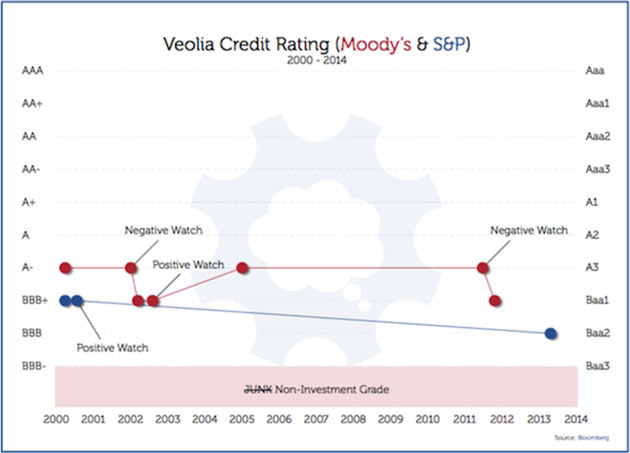

During the life of Veolia, the credit ratings agencies have taken something of a skeptical view of the company’s prospects with both Moody’s and S&P keeping their credit ratings just above the chasm between investment grade and junk throughout the company’s seventeen year existence (chart below).

Source: Bloomberg

Quelle surprise then, when Société Générale announced that the company’s €500 billion 3-year unsecured notes would be priced to yield... wait for it... -0.026%.

Yes, that’s right folks, a BBB-rated company managed to convince investors to pay them, at issuance, for the privilege of lending the company money.

I make this distinction around a new issuance because, amazingly, Veolia already has a bond trading at a negative yield.

The company’s 4.375% issue due December 2020 spent the first three years of its existence declining in value as the yield moved from 4.375% to 7.5% and then... QE happened.

In March 2009, the company’s bonds were yielding 6.5% but once central banks began buying bonds, that yield began looking juicier by the day and so the frontrunners bought them to later sell to the ECB and the yield just kept on falling – all the way to the zero bound and below.

Alongside Veolia, thanks to the lunacy largesse of the European Central Bank’s bond purchase programme, sit another five companies, all of which are rated BBB or lower by S&P and all of which currently have fixed coupon bonds yielding less than zero.

All of the sub-zero club are utilities (AffinityWater and South EastWater in the U.K., Germany’s Innogy SE and two Italian companies, A2A

SpA and Enel SpA) and all of them seem to have convinced investors (if not the ratings agencies) that they are worthy of membership of this little club because their cashflows are nice and steady.

Or something...

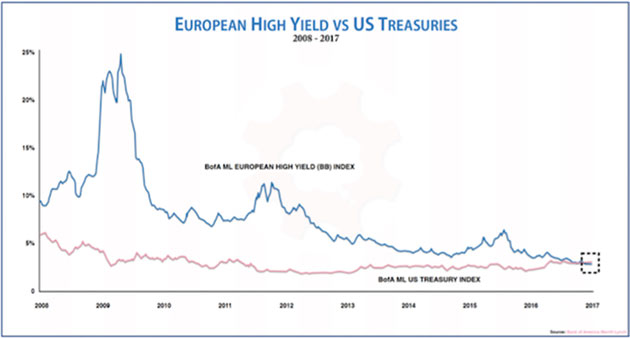

This is part of a wider phenomenon which [this] chart … highlights beautifully:

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch

Bond markets have also reached the blow-off insanity phase BUT, that insanity is being concentrated in places where a guaranteed central bank bid makes a lot of sense and provides a huge tailwind to investors who are once again bent over at the spigot and drinking as fast as they can.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario