How to Retire on 2% Returns

By Patrick Watson

Does the past predict the future? If you work in the regulated financial industry, you can only answer that question two ways. Your acceptable answers are:

- No

- Not necessarily

When I used to write commodity and hedge fund marketing materials, I typed the official phrase, “Past results are not necessarily indicative of future results” so often, I finally gave it a hotkey on my computer.

That’s not to say the past is irrelevant. It can tell us a lot.

If you can identify a pattern in economic cycles or market activity and have enough observations to make your observation statistically significant, it raises your odds of success.

The fact that most people do this badly doesn’t mean it can’t be done at all.

Talent exists; it’s just hard to find.

Talent exists; it’s just hard to find.

That’s why John Mauldin’s Strategic Investment Conference is such a boon.

Last week, he gathered some of the world’s most brilliant investment thinkers in one place and let them speak their minds.

Last week, he gathered some of the world’s most brilliant investment thinkers in one place and let them speak their minds.

Better yet, he turned the experts loose on each other by grouping them in panels. Those discussions were pure gold.

I heard some things I didn’t especially like, but there is no true bliss in ignorance, no matter what the folk wisdom says. Today, I’ll tell you about one of speakers and what I learned from him.

Slow Growth Ahead

I started reading Martin Barnes probably 25 years ago when I worked at ProFutures. My boss, Gary Halbert, was a big fan and let me read his copies of the very expensive Bank Credit Analyst, which Barnes edited for many years.

BCA doesn’t always catch short-term moves, but its long-range macro outlook has been reliable. I was thrilled to finally meet Martin in person last year at the Camp Kotok economists’ retreat—and this year, I got to hear him speak at the SIC.

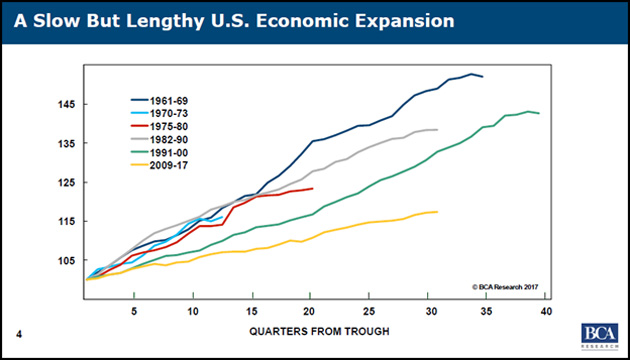

Martin believes the current slow economic expansion will continue. He showed this slide comparing the length and magnitude of past US growth cycles.

The bottom yellow line represents the current recovery, which has produced less GDP growth than prior cycles. But in terms of length, it is now tied for third place, surpassed only by the 1961–69 and 1991–2000 expansions.

If it lasts two more years, it will be the longest on record.

Martin thinks it could happen: “Expansions are typically assassinated. They don’t die of old age,” he said. In most cases, the assassin is monetary policy.

The good news this time is that Martin doesn’t see the kind of imbalances that would make the Fed go overboard. With inflation relatively subdued, he thinks the tightening won’t be too tough.

He also noted that President Trump’s tax cuts and stimulus spending plans would have overheated the economy and probably led to a 2019 recession. With gridlock winning, he sees this as a minor risk.

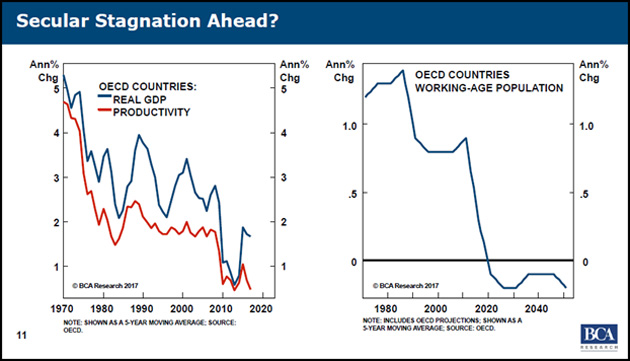

The bigger problem is that other macro trends aren’t helping. Worker productivity and working-age population are problematic already, and they will likely get worse.

This being the case, Martin thinks we can’t expect the kind of investment results seen in prior expansions. Over long periods, stock market growth has to track economic growth. Market gains since 2009 reflect good news that hasn’t actually happened yet.

Which brings us to the bad news I mentioned.

Martin thinks the 2% average real GDP growth of this expansion will likely continue for the next decade—and in the long run, stock benchmarks can’t grow more than the economy in which they operate. That means net investment returns will stay around 2% as well.

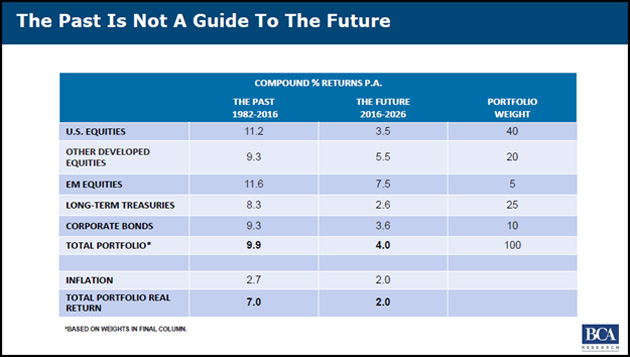

Here’s what BCA expects, broken down by asset clases.

From 1982 to 2016, a static stock/bond portfolio delivered real (after inflation) returns around 7%. US equities alone averaged 11.2%.

Consider those the “good old times,” though, because Martin Barnes doesn’t expect any more of it.

This is a big problem for investors who are planning their retirement on the assumption that they will earn inflation-adjusted returns well above 2% and are saving and investing accordingly.

Worse, many public pension funds still assume their portfolios will earn 7–8% nominal returns and make promises to workers based on that assumption. If Martin is right, this is not going to end well for either workers or taxpayers.

What can you do?

Overestimate Your Enemy

Also at the SIC was George Friedman of Geopolitical Futures. He said something in an entirely different context that fits here too.

In discussing the United States’ response to North Korea’s recent missile launches, George said, “It’s important to always overestimate your enemy.”

To George, this means the US has to assume North Korea’s nuclear capabilities are real, and act accordingly.

To investors, it means we shouldn’t assume 7% real returns will continue.

Maybe Martin is wrong and the market will zoom higher in the next decade—but your retirement plan shouldn’t bet on it.

Maybe Martin is wrong and the market will zoom higher in the next decade—but your retirement plan shouldn’t bet on it.

In other words, keep your expectations conservative. Better to be surprised by a windfall than a shortfall.

Specifically, you can start by tempering your retirement lifestyle plans. That could mean pushing back your planned retirement age, living in a less expensive home, or renting out part of your house to lower expenses.

You could also save more aggressively for retirement, which might require reducing your current spending plans. You’ll be glad you did later.

Finally, reconsider your investment strategy.

You‘ll notice in the BCA forecast that they expect the highest future returns to come from emerging-market (EM) equities. I agree—which is one reason I recently recommended a reduced-volatility emerging market ETF to Yield Shark subscribers. It’s up almost 3% so far but still has plenty of room to grow.

What you absolutely shouldn’t do is assume the future will look like the past.

But while you can’t predict the future, you can still control your response to it.

Make sure your strategy won’t disappoint you.

But while you can’t predict the future, you can still control your response to it.

Make sure your strategy won’t disappoint you.

See you at the top,

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario