What Should Trump Do?—Your Questions Answered

By John Mauldin

However, last week’s letter with my thoughts on what Trump should do generated more responses than any other letter had in the last 17 years. As you might suspect, with a topic so controversial, not everyone agreed with me. But there were many good questions and comments and some thoughtful disagreements, so I want to address a few of those. And I will specifically go into why I seemingly deviate from core conservative principles regarding taxes. It’s all about debt and the consequences of debt – that’s the overriding factor for me. And I’ll try to make the case that there are times when we just have to make hard, even philosophically unpalatable, choices.

Some comments I will excerpt; others I will characterize in general terms; and where appropriate I’ll copy and paste whole comments. So let’s jump in.

Allen Jones · Univ. of Arkansas

Please explain further corporate tax rate of 15% on income above $100,000 with "no deductions period." Sounds like a 15% tax on sales. What do you mean no deductions? Are operating expenses deductions?

Allen, this was probably the most-asked question, and since you asked it most concisely, you get the recognition for it.

No, this is not a sales tax. It is a 15% tax on corporate income. That is normal GAAP accounting income. There are something like 3,400+ different, legal, congressionally mandated corporate tax loopholes and deductions. (I can’t find the exact number right now.) Many of those tax loopholes apply to only one company or one very small industry and are favors from a Congressman or Senator to their main constituents. So when I say no deductions, I mean get rid of every one of those loopholes. I know, I know – I will be goring practically every business’s ox in some way or other. And that’s the problem: Too many people think their industry deserves some breaks and one little loophole is not that big a deal, and the next thing you know there are 3400 of these puppies. And then you find General Electric paying less income tax than I do while making multiple billions of dollars a year.

I might be run out of Texas, because this would likely mean axing the oil depletion allowance, too. Normal depreciation would still apply. For those who are worried about R&D expenses, I would allow accelerated depreciation on R&D, because those are truly expenses, at least in my mind. But the point here is to have as few loopholes as possible (with the only exceptions to be those that clearly, directly create jobs). I will readily admit to not being an accounting expert, but I have looked at a few balance sheets.

Corporations would have to pay taxes on what they report to their shareholders or their bankers or even to themselves. Fifteen percent is not that big of a deal in the grand scheme of things. It is actually slightly lower than the current effective rate (depending on which source you go to). I think that under this plan we would actually take in more taxes because we would see corporations come from around the world and domicile here in the United St ates. And businesses would not go to such drastic lengths to avoid reporting income, so total corporate taxes would increase.

Glen Travers -· London, United Kingdom

VAT is a drag on growth – look at UK and EU – as well as difficult for the unhappiest group in all our economies. This insidious tax is an admission of failure by politicians who promise reductions in income tax in return for proposing a “fairer” direct tax instead of controlling populist unaffordable promises.

Glen, I totally agree with you: a VAT will be a drag on growth. There was a lot of pushback from many readers on the concept of the VAT. So let’s use your question as a springboard into the subject.

First, if you asked me 10 years ago if I would ever even think about a VAT in the US, I would’ve said, “Not no, but hell no. Double hell no!” We were still at a point in 2006 where we could have brought the budget under control, got our hands around the entitlement problems, flatlined spending along the lines of Clinton/Gingrich, and dealt with both the deficit and the debt.

However, that is not what we chose to do. And now we find ourselves between the devil and the deep blue sea. The devil is the national debt, and the deep blue sea is the crisis that we are sailing into if we don’t figure out what to do about that debt.

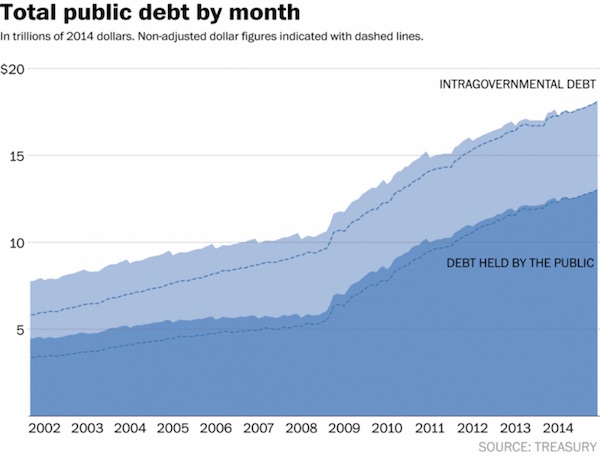

The chart below goes through 2014, and if it were extended to the end of this year it would show national debt at $20 trillion.

At some point, Glen, debt in and of itself is a drag on growth relative to income. The economic literature is pretty consistent on that. A debt-to-GDP ratio of 40% is not an issue; but US government entities owe a total of $23 trillion, or over 120% of debt-to-GDP – and that amount is rising every year. We look a lot more like Italy than any of us would care to contemplate.

While I agree that a VAT is a drag on growth, that is not the problem in Europe. It is their debt, plus their sclerotic regulatory systems and ungodly heaps of rules and regulations that are destroying jobs and inhibiting new small businesses from starting.

As I keep preaching, when (not if) we have the next recession, the will balloon to well over $1.5 trillion and probably closer to $2 trillion. It won’t take long to get to $ trillion, and then we’ll be spending $600–$800 billion of taxpayers’ money just to pay the interest at what I think will be normal rates. Now, if you prefer to use the CBO’s projected interest rates, then add another $300 billion a year, pushing total interest outlays to $1 trillion a year. (The CBO is assuming a much stronger economy than I would at that level of debt.

If I am wrong, then the interest payments will be much higher…)

We have amassed well over $120 trillion in unfunded liabilities, and if we don’t get our entitlement spending under control, the debt is only going to get worse – much worse. That reality brings up the next, generalized question.

John, you know the only real way to solve the crisis is to cut spending across the board. Cut everything. You have to slash entitlements and defense spending and get rid of whole government departments. We have to learn to live within our budget. Stop being part of the mainstream and deal with the real problem: too much government spending.

(And there was also the Libertarian variation on that theme: Starve the beast; don’t feed it.

To everyone who voiced sentiments along those lines: I get it. I agree with you. If it were in my power, I would do it. But it’s not.

There’s a song running through my mind right now. It’s the chorus from Kenny Rogers’ classic song, “The Gambler”: “You got to know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em…”

Philosophically, I am still as much a small-government guy as I was back in the ’80s. A small-L libertarian. I want government to do only what is necessary to keep the game fair, do the things that we need to do as a group, which can mostly be done on the local level – and for God’s sake keep its thumb off the scales.

We fought those battles in the ’80s and ’90s and made huge progress – and we truly lost at a national level when the Republicans took over under Bush II. We Republicans became the party of big government. And while you can get many Millennials and Gen Xers to nod in agreement with the principle of a small government, for them that does not include doing away with government-assisted healthcare, which by definition means a pretty large government. And don’t even try to touch the hot third rail of Social Security.

Bush II actually tried to deal, just marginally, with relatively simple problems with Social Security and got slapped down by both parties.

Tell Boomers and others they can’t have their Medicare? Or their other “entitlements”?

The simple fact is, a majority of the voters in this country want Social Security and healthcare and expect healthcare to be provided to those who can’t afford it. They want pre-existing conditions to be ignored by insurers. And a whole slew of other things.

I do believe there is a way to get healthcare spending under control and put our entitlement problems on a glide path to being solved, even as we fully acknowledge that our demographics are working against us. But there is no way it can be done without money. It is going to take a great deal of government spending, no matter how you slice it. The government has only three sources of revenue: taxes, borrowing, and monetization. Borrowing money runs up the debt, and we are getting very close to the point where ballooning debt becomes debilitating. More on monetization later.

That means we have to somehow increase revenues if we are going to pay for all that needed spending and bring the debt under control. I don’t like it, but those are just the facts.

So then we come to the crux of the matter: How do we raise the necessary revenue in a manner that will still allow us to grow the economy as much as possible? I think the preponderance of economic literature suggests that consumption taxes are in general less of a drag on growth than income taxes.

Consumption taxes include value-added taxes (VATs) and sales taxes. Then there is a whole school of thought built around the so-called Fair Tax, which is a national sales tax that would be added on to all retail sales in addition to state sales taxes.

Proponents of the Fair Tax would then eliminate all federal income taxes (including the alternative minimum tax, corporate income taxes, and capital gains taxes), payroll taxes (including Social Security and Medicare taxes), gift taxes, and estate taxes.

I can go along with this scheme in principle, but in practice I think the equivalent of a 30% sales tax (which is what the Fair Tax would amount to when combined with state and local sales taxes) would send a lot of the economy underground. Just my opinion. When you can deal with your plumber or favorite restaurant for 30% less by paying cash, the temptation looms pretty large.

I’ve traveled all over the world, and those countries with high retail taxes or controlled exchange rates end up becoming cash societies to the extent possible.

The Argentines and the Greeks and the Italians are lifetime grandmasters at surviving in such an economy. Call me cynical, but at 30%, I think a lot of my neighbors would quickly master the game, too.

A VAT, or any of its sisters, has the advantage of being taxed at the business level on the incremental value added to products at each stage of production. It is thus a great deal harder to avoid, so everybody pays. Or almost everybody. It would actually capture a lot of the current underground economy.

So why not make the VAT large enough to get rid of all the other taxes, as the Fair Tax folks suggest? For me, it’s is a purely political decision. The VAT is a regressive tax. That means it generally falls more heavily on those with lower incomes. And progressives and liberals will hate that. So we have to come up with a compromise. That means we’re still going to have to have an income tax, but we need it to be as low as possible. My suggestion is 20% on all income over $100,000. (See last week’s TFTF for details.)

To make the VAT less of a regressive tax, I propose that we make it large enough so that we can eliminate the Social Security tax. That immediately gives all lower-income earners a 6% pay raise. Plus, it lowers business costs 6%. That takes away a lot of the regressive nature of the VAT.

Not starting to pay income tax until you clear $100,000 and not being taxed for Social Security doesn’t mean that those who make between $50,000 and $100,000 don’t pay taxes. They pay taxes in the form of the VAT, plus their local taxes; so their tax burden should not be a lot different than it is now, and they might even see something of a tax cut.

Remember, the object here is not just to cut taxes but to figure out how to get more tax revenue with the least possible pain to the overall economy. If your family has ever been faced (as mine has on several occasions) with a significant increase in expenses or decrease in income, you know you had to make some tough choices.

On the national level, too, somebody is going to have to pay more, and somebody is going to get less. I remember that when I was starting out in business in my 30s, there were days when I darkly joked, “I’ll pay what I have to, and everybody else will have to wait.” That included my wife and kids and what they wanted or even needed. Reality’s a bitch sometimes.

We have a reality to face up to now. And that is our national political process. We have to figure out where to get the money to pay for what our citizens say they want. If a Republican president and Congress do not enact legislation that gives voters something approximating what they feel they need, Republicans will be thrown out and Democrats will be given another chance. Let me tell you straight up that the economists advising the Democrats will not only give us a VAT, they will give us high progressive personal income taxes, and the corporate tax will not come down that much. They simply don’t buy my economic view of the world. They are neo-Keynesians through and through. Think Europe on steroids … even as we watch Europe getting ready to implode over the next four years.

There are a number of objections along the lines of, “If we do what you propose, it will hurt me. It’s not fair.” Well, in many cases I agree and sympathize with you. But at this point in the game, our whole political and economic situation is “not fair;” and we’re left with only difficult (but necessary) choices. One especially poignant objection came from a reader who had converted his entire pension plan to a Roth IRA, paid his taxes, and now I was, proposing a VAT that would make him pay his taxes again. He is quite right that this is unfair to him. But I don’t know what to do.

It is simply not possible to devise a system that is fair to everyone in every way. We have to make some tough decisions. The needs of the many must outweigh the needs of the few. And I say that with a full understanding that, as Ayn Rand discovered and explained, the needs of the individual are what give rise to the need and possibility for value judgments to begin with.

That is the problem with making decisions in a government that is as big and complex as the US system is. We have let its growth get out of control, and going back would be so unbelievably disruptive in terms of lives and fortunes and jobs and futures that the reverse trip is simply not possible. We can’t rewind the clock.

As The Gambler told us, “Every hand’s a winner and every hand’s a loser.” We have been dealt the hand we have, and we have to figure out how to play it to make it a winning hand. Folding is not an option.

What Happens If We Don’t Balance the Budget?

And thus we come to the heart of the matter with regard to my VAT proposal. If we don’t bring the budget deficit beneath the nominal growth rate of GDP (which is unlikely to go above 4% in the near future), our debt will explode during recessions; and we will ultimately face a debt crisis. Those never end well. The choices we will have at that point will be far fewer and even more stark.

Let’s wargame our situation for a few minutes. What will happen if we increase taxes and cut spending enough to get the deficit and debt under control? Getting there will take compromises along the lines of what Clinton and Gingrich did, but I truly hope we’re capable of them. With our debt as large as it is, we are going to be in a somewhat slower-growth economy; but if we get rid of enough shackles on growth and get the incentive structure right with the proper tax mix, the American entrepreneur can probably get us out of the hole we’re in without its getting too much deeper.

With the amazing new technologies that are coming along, we can probably get to a point where we can in fact grow our way out of our debt problem over the next 10 to 15 years.

What happens if we don’t? The more benign outcome is that we end up looking like Japan. We grow the debt to the point where we actually have to monetize it.

Perhaps not the end of the world but certainly not the high-growth, job-creating machine we would like our economy to be. The income and wealth divide would deepen, and if you think there was pushback in the last election, just wait. We might see even higher taxes and a slower-growth economy; and entrepreneurs, established businesses, and investors would just have bigger headaches. Remember, that’s the best possible outcome if we don’t deal with our deficit and debt.

What happens to the value of the dollar in that scenario? Six years ago I would have confidently told you it would go down. Now, as I observe the Japanese experience (and even though I recognize a number of differences between our economies), I suspect that the dollar might rise, not fall. Or rather, it wouldn’t fall relative to the other global currencies, and not nearly as much as my hard-money friends seem to think. We would truly find ourselves in a world for which we have no historical analog.

If the country with the world’s reserve currency starts printing money merely to service its debt because people don’t buy its debt, and in a world where most other major economies are also in trouble (as I logically assume they would be), then where are we?

And remember, this would be a future in which total global debt would be in the $500 trillion range and global GDP would top $100 trillion. Monetizing $1–2 trillion a year (we are talking 10+ years out) – roughly the equivalent of what Japan is doing today – might be like spitting in the ocean. Money will be far more fungible and liquid and movable in the financial-technology world that we are evolving to. It would be the height of hubris to think we can know with any degree of certainty what would happen.

Now I don’t think the failure-to-act scenario will happen, but we’re in wargame mode, so we have to think the unthinkable. Maybe the world decides it wants another reserve currency or substitutes something new. We don’t know. Lots of things are going to be possible in 10 years that we have no clue about today. In such a scenario, the dollar could in fact lose a great deal of its purchasing power.

That would create a great deal of uncertainty and volatility, and I can see a global deflationary debt scenario unfolding, followed by massive monetary creation.

I guess the critical factor for me is that I can see no scenario where we don’t deal with the deficit and the debt and enjoy a positive outcome. It’s a binary choice to me.

So I choose to suggest what I think is the only politically possible thing to do; and that is to restructure the tax code, balance the budget with an increase in taxation, roll back as many rules and regulations as we can, hope we get the healthcare issue right – and then see what happens.

Let me end with a story. I was on a plane going from New York to Bermuda and had been lucky enough to be upgraded to first class. It was 1998 – just a few days after the resolution of the Long-Term Capital Management crisis. The markets had seen a rather harrowing time.

The gentleman who was seated next to me ordered Scotch as soon as the wheels were up and basically indicated to the stewardess to keep them coming. You could see that he was emotionally shaken. I engaged him in conversation after a few drinks, and when he found out that I was allied with the hedge fund business and coming from New York, he assumed I knew a lot more about the world than I did. It turns out that he was the vice-chairman of one of the largest banking conglomerates of the time. We all know the name.

He began to relate to me the deep background story of what had gone on for the past few weeks, culminating in that famous meeting called by the New York Federal Reserve, where the president of the New York Fed told everybody in the room to play nice in the sandbox. And to whip out their checkbooks. This gentleman had been in the meeting and knew the whole story. I knew I was hearing something special, so I just sat and listened and made sure the flight attendant kept bringing Scotches for him. He seemed to open up more with the downing of each one.

Finally, he turned and looked me in the eye and said, “Son, we went to the edge of the abyss, and we looked over. And it was a long way down. It scared every one of us to the depths of our soul.” And then he ordered another Scotch and laid his head back and tried to rest.

As I look back on that 1998 crisis, which we all thought was so huge at the time, it brings a smile. We were talking hundreds of millions that had to be ponied up by each of the big banks, several billions of dollars total. It was manageable within the private system. Just 10 years later, in the 2008 crisis triggered by the housing bubble, we were talking hundreds of billions if not trillions in losses, and the private system was not capable of dealing with it.

If we don’t handle our debt problem, the crisis into which we’ll plunge will resolve the debt in one way or another – and the ensuing turmoil will make 2008 look as minor as 1998 does today.

I do not want to my children to wake up in a world where we are frog-marched to the edge of the abyss and forced to look over. We still have the opportunity to secure the future for our children, but only if we seize the moment. If we don’t, it will be unusquisque pro se – every man for himself.

A few thoughts on investing in an environment like this (since investing in the economy is supposedly what this letter is mostly about). With all the current and emerging challenges we face, investing will still be difficult even if we deal with our debt issue, but those challenges will be far more agreeable than the extraordinarily difficult choices we’ll be left with if we don’t handle the debt. With the tools and strategies that we have available to us today and with even more powerful tools being developed for the future, I think investors who are properly prepared can figure out what to do in either scenario. But average investors who are expecting the future to look somewhat like the past? They’re going to be severely damaged.

Their retirement futures are going to be ripped from them. And they are going to be profoundly unhappy.

None of that has to be, of course. Things might turn out just fine. But I have a strong suspicion that the massive move we are seeing from active management to passive management strategies in the past year is going to turn out to be one of the all-time worst decisions by the herd. But that’s a topic for another letter.

I was truly saddened to learn this week that my old friend Howard Ruff had passed away.

He was 85 and suffering from Parkinson’s. Howard Ruff is a name that my younger readers (under the age of 40) will likely not recognize, but those of us who were around for the investment world of the ’70s and ’80s were certainly influenced by Howard. He was one of the true founders of the investment publishing world and was clearly the rock star in the ’70s and ’80s. His main newsletter was called the Ruff Times. This title was appropriate, as his first three books were Famine and Survival in America (1974), How to Prosper During the Coming Bad Years (1979 – NYT #1), and Survive and Win in the Inflationary Eighties (1981) – all solidly in the gloom and doom camp. Howard believed (as of his 1979–1981 writings) that the United States was headed for a hyperinflationary economic depression and that there was a danger that both government and private pension plans were about to collapse. His mailing list grew to over 200,000 subscribers (unheard of for a newsletter at the time), and he had a following that was amazing. He was part of the hard-money crowd and rode the wave of gold and food storage, preparedness for the coming crisis, throughout the ’70s and into the ’80s. He made a series of remarkable calls, and people thought he knew what he was talking about. I think that sometimes even Howard himself did. (You can read a fuller reminiscence by our mutual friend Mark Skousen here. (Also includes a link to a New York Times piece on Howard.)

I remember the first time I saw him. I was at an investment conference in New Orleans (the “gold conference” which in its heyday would have 4,000 attendees and was founded by another legend, Jim Blanchard), and I noticed a small crowd (100 people or so) focused on an individual in a hallway. It was Howard holding court, answering questions, just being his entertaining self. And people leaning in to listen – enraptured. I saw that scene repeated at other times during that and other conferences, all throughout the ’80s.

And then things changed. The markets changed, and Howard’s message didn’t. His subscriber list began to shrink. The crowds got smaller (and older). You have to understand, Howard was a complicated man. He went through multiple bankruptcies and came back to make millions. He was passionate about everything he did. The business setbacks were simply opportunities to move on to something else. Onward and upward.

He was always upbeat.

He was a devout Mormon who had 14 children, 79 grandchildren, and 48 great-grandchildren at the time of his passing.

Sometime in the middle of the last decade I was speaking at an investment conference in Las Vegas. Howard called me and asked if he could come down from where he lived in southern Utah to give me a copy of his new book (which he wanted me to review). You can’t tell a force of nature no, so I told him to come on down. We agreed to meet at a booth on the exhibit floor in the afternoon. The floor was rather busy, and I was talking with friends and attendees at the back end of the aisle. I looked down the aisle and saw Howard walking toward me, and it wasn’t until he was about 10 feet from me that I realized that no one had stopped him to have a chat. Howard was still the same person, but the world had moved on, and he had not moved with it. I vividly remember thinking sic transit gloria. That lesson, the thought that it could happen to anyone, has been seared into my brain over the last 10+ years.

He wrote a biography in which he talked about his successes and failures, and we compared notes on his career and mine from time to time when we had opportunities to get together. I had jumped in near the beginning of the investment publishing business but on the management side, and I didn’t begin to really write my own material until the late ’90s. Howard was glad to mentor me and freely talk about his ups and downs.

He shared what he considered to be his biggest mistake. In the early ’80s, and certainly by the mid-’80s, he began to realize that inflation was truly not coming back and that gold might be challenged. But he had well over 100 employees and a subscriber base that would rebel if he changed his tune. Changing his message meant he would have to lay off scores of people, including many friends and family members, and he just couldn’t bring himself to do it. “I knew it, in my heart, but I just couldn’t get myself to damage the company that badly.”

We had that conversation several times. I have had the unique advantage of being friends with a number of writers and publishers over the last 35 years. I’ve seen writers get big and then fade. Other seemingly stay on top of their game, riding the wave wherever it takes them. The biggest mistake that leads to downfalls is believing in your own investment magic (or, as we are wont to say in Texas, believing your own bullshit).

Howard was a true, one-of-a-kind marketing genius; and if he had changed his tune when he knew he needed to, he would have lost half his readers, but he would have built his list back up. The lesson: Be true to what you know and believe, and let the chips fall where they may. Don’t tell the people what they want to hear, Howard would say, but what you really think. Just make sure you believe it.

Howard was a friend to everyone he met, forever generous with his time and resources.

Those of us in the investment publishing world owe a great debt, whether we know it or not, to Howard Ruff. Your publishing business has Howard’s DNA buried deeply within it.

May he rest in peace.

I have rarely asked my readers to connect me with someone; but when I have, I have never failed to get that email address or phone number. So with that hope in mind, could someone please give me email and/or phone connections for both Matt Ridley and Bill Gross? You can send them to mary@2000wave.com. Thanks.

Week after next I will make my way to Washington DC and New York for a series of meetings and then to Atlanta for a Galectin Therapeutics board meeting. Then I’ll be home for the holidays. I’ll be in Florida for the Inside ETFs Conference in Hollywood, Florida, January 22–25. And then I’ll be at the Orlando Money Show February 8–11 at the Omni in Orlando. Registration is free.

It’s time to hit the send button. After writing such dramatic and emotional content, I think I’ll go watch the latest Harry Potter movie and simply be entertained. I am still utterly amazed that I can make a living doing what I enjoy doing – writing and thinking and talking. Every time I sit down at this computer to write my letter, I truly do think, “Dear God, don’t let the magic stop this week.” But then the real magic is you. It’s been 17 years, and I still enjoy every step of our journey together. Thank you.

Remember, I really do read your comments and take them to heart. So if you want to tell me something, go right ahead. In the meantime, you have a great week. It will be interesting to see how Trump transitions from showman to President, from a candidate who can say anything to “Oh my God I have to make decisions, and this is the real world.” Maybe I’m asking for the triumph of hope, but I believe he can.

Your whispering memento mori analyst,

John Mauldin |

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario