How to Rebuild Healthcare Right

By John Mauldin

“I reject the insurance model. I think we should have a free-market approach to healthcare.”

– Gary Johnson

“The goal of real healthcare reform must be universal coverage in a cost-effective way.”

– Bernie Sanders

“The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves….”

– Julius Caesar (I.ii.140–141)

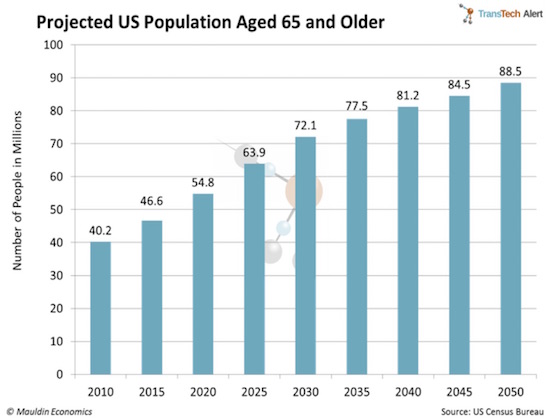

“The numbers [referring to the growth in the aging population and its relationship to Alzheimer’s] point to a disaster that will be the real zombie apocalypse. Western societies simply won’t be able to bear the costs of Alzheimer’s as the incidence continues to rise. Faced with impossible financial, emotional and psychological costs, we would have to funnel so much of our resources into the care of Alzheimer’s patients that the quality of life for everyone would plummet.

“Escape from the zombie apocalypse, on the other hand, is entirely simple: cure aging itself. To be more precise, the solution to Alzheimer’s is to stop accelerated aging. We need to slow the degeneration that leads to Alzheimer’s and other age-related disease.”

Is inflation something to fear, or we should demand that our central bankers craft policy to nudge inflation upward? There are genuine arguments about this, and I have written about the problems we have even tracking inflation, much less guiding it toward a target.

However, one area where we have no problem detecting inflation is medical expenses.

They seem to go nowhere but up, as I described in last week’s “Taking a Wrench to Healthcare.” Millions of Americans are about to learn how much their Obamacare premiums will be next year. But even if you have health coverage through your employer, or you’re 65+ and on Medicare, like me, I can all but guarantee severe inflation in the healthcare part of your budget.

I ended last week by saying I would describe a possible solution to the healthcare quandary. Today we’ll look at the remarkable results the Cleveland Clinic has already achieved with its 100,000+ employees and dependents and with numerous corporations they work with. They are making people healthier and reducing medical costs. It is a model that I think could work on a much broader scale.

Much of what you are about to read came by way of my own physician at Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Mike Roizen. He heads their Wellness Institute and is the author of a best-selling book, This Is Your Do-Over: The 7 Secrets to Losing Weight, Living Longer, and Getting a Second Chance at the Life You Want. I highly recommend it.

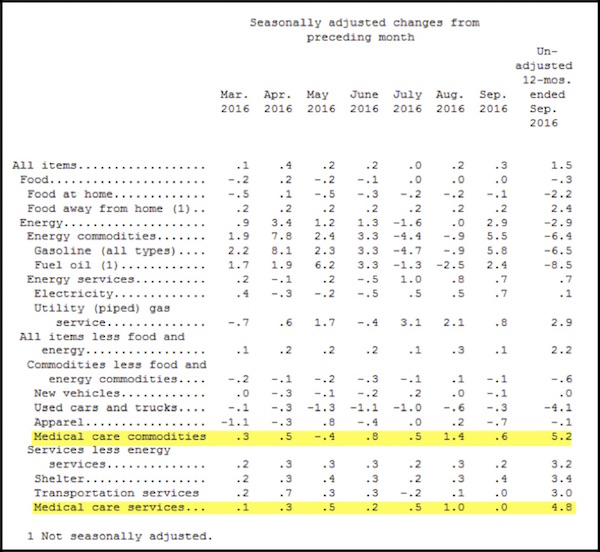

Last Tuesday’s US Consumer Price Index lets us attach numbers to the problem.

Here is the official CPI summary table. I have highlighted in yellow the relevant lines:  Direct your attention to the rightmost column, which shows the 12-month change through September 2016. CPI for all items rose 1.5% in the last year. Prices actually fell in the energy-related components, as much as 8.5% for fuel oil. Great news if you are a heavy fuel oil user. Most people aren’t. Fuel oil is used mainly in the Northeast and is less than 0.1% of the overall index. On the other hand, total medical care is 8.375% of the index (and rising).

Most people use healthcare, and those components showed the highest cost increases in the report. The medical care commodities category includes prescription and nonprescription drugs, as well as medical supplies. The medical care services category includes doctors, hospitals, lab tests, etc., as well as health insurance premiums. Both categories popped much higher than any other CPI components in the last year.

Keep in mind that your personal CPI depends on your spending patterns. Medical care is a bigger part of the budget for most retirees, as well as for younger people with chronic conditions. Your own all-items CPI change was probably much more than 1.5%. If you drill down in the full CPI release, you’ll see that the health insurance subcategory rose 8.4% in the last year. That’s money you spend whether you actually use any services or not. It’s also a national average that disguises the much higher increases for many folks.

Incidentally, one of the maddening things about analyzing healthcare costs is that comparisons over time are almost impossible. Very rarely does anyone get to buy the exact same insurance plan that they bought last year. The insurers change terms, raise deductibles and co-payments, exclude certain drugs, and revise their provider networks.

(It was only a few years ago that my deductible was $500. Now it’s $5000 and I am paying more for the insurance.) So not only did your premiums rise by an average 8.4%, they probably also bought less coverage than you had the year before. If it were possible to again buy the exact same coverage, your annual increase would almost certainly be more than 8.4% and possibly much more.

(Sidebar: the people at BLS who figure out what the CPI is use something called hedonics, which allows them to say that the prices of some things, like electronic, are going down because their quality is going up. Even if you are actually paying more, they figure you are getting more for your money, so that’s not inflationary.

The BLS does not apply the same concept to healthcare. Even though the price is rising, they do not adjust for deductibles or reductions in what is covered. If taken into account, those factors spike the healthcare inflation number significantly. Just saying…)

What specific conditions drive rising health insurance premiums and medical costs? We hear about expensive prescriptions and the high costs of surgery and hospitalization. We’ve seen friends and relatives spend their entire life savings on cancer treatments. The numbers are staggering.

I was with a longtime neurological surgeon yesterday at an investment conference, and he critiqued last week’s letter on healthcare costs. He said the real reason for the rise in healthcare expenses is greed. And there is a great deal of truth to that.

We have more hospital beds than we need and in the wrong places. Many procedures are unnecessarily prescribed, and the list goes on and on. The way insurance is provided and the insurance companies that provide it are a big part of the cost issue, too.

There is no price discovery available for many products, so there is no control on cost. I recently found that I can buy an extremely high-quality prime rib from Costco for about 30% of what I pay at local high-end meat markets. Guess where I will be buying my prime rib roast next Thanksgiving? I have no such way to compare healthcare costs. In a world where everything else is available for comparison online, it is criminally negligent not to make healthcare costs publicly available.

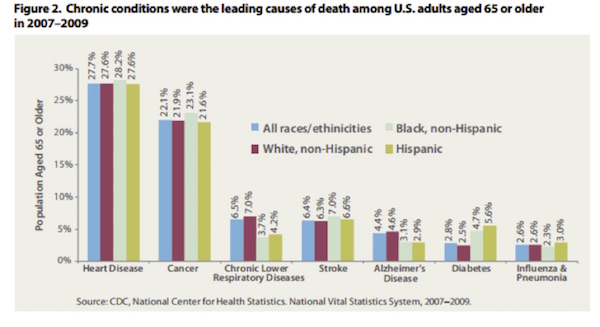

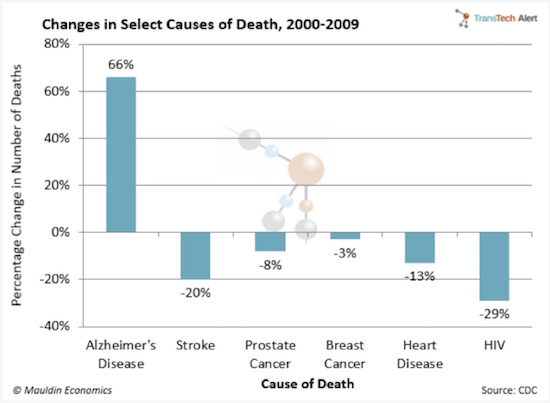

Nevertheless, those kind of expenses aren’t the main challenge. In some respects, they are merely symptoms of the real problem. The chart below from a CDC study shows the leading causes of death among adults age 65 or older. It is a few years old, but from what I can see researching online, there has not been much change except that the numbers for these chronic conditions are still going up.

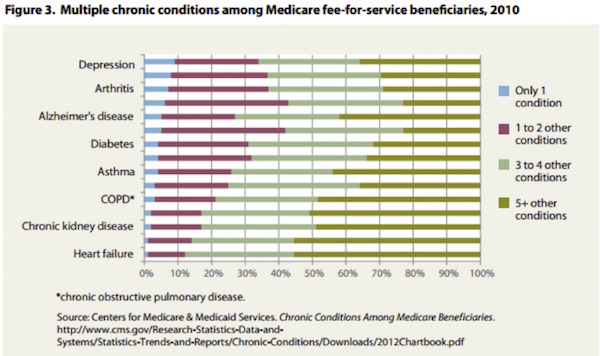

And once you have one of these chronic conditions, the general trend is that you end up with multiple conditions, often as many as five or six.  What is it that makes us susceptible to cancer, heart disease, and other debilitating (and expensive) ailments? Deal with that, and people won’t reach the point where they need expensive care.

Cleveland Clinic says six chronic health conditions cause most of our problems. They are:

Keep in mind that we are talking about the United States. These conditions are not so prevalent everywhere. They are spreading, though, as the US goes on exporting its lifestyle to the rest of the world. Diabetes rates are skyrocketing in China, for instance. China now has almost 90 million people with diabetes. People there now consume more calories and burn fewer calories living in cities than they did as farm workers. Similar patterns are evident almost everywhere. The rest of the world can laugh at overweight, unhealthy Americans now, but they are on track to be just like us in 10 years.

Our diet is a key problem. To be blunt about it, Americans eat too much. We could certainly improve our diets by avoiding excess sugar, carbs, etc.; but Mike Roizen says the real culprit is portion size. We live in a culture of excess. Furthermore, producing, distributing, and marketing food is a huge part of our economy. We make money by encouraging each other to eat more than we should. Farm-state politicians get elected by pushing policies that make food cheaper and more plentiful but not necessarily more healthful.

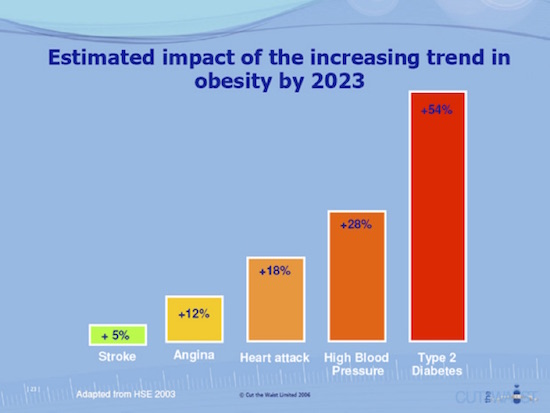

Our national food obsession is literally killing us. It is so deeply engrained (pun intended) that we seemingly just can’t turn it off. And this trend toward obesity is showing up as an increase in disease.

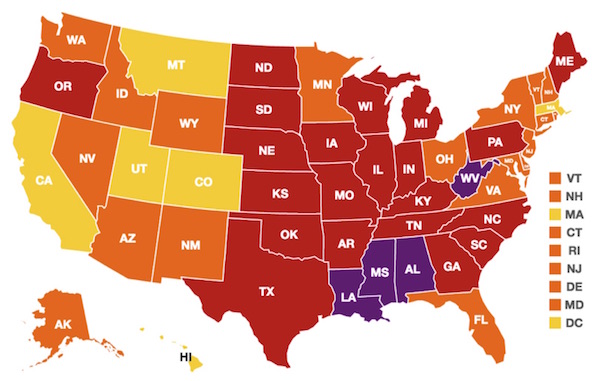

Obesity is one of the biggest drivers of preventable chronic diseases and associated healthcare costs in the United States. Currently, estimates for these costs range from $147 billion to nearly $210 billion per year. Individuals with lower income and/or education levels are disproportionately likely to be obese. More than 33 percent of adults who earn less than $15,000 per year are obese, compared with 25 percent of those who earn at least $50,000 per year. According to the most recent data, adult obesity rates now exceed 35 percent in four states, 30 percent in 25 states, and are above 20 percent in all states. Louisiana has the highest adult obesity rate at 36 percent, and Colorado has the lowest at 20 percent. (source: http://stateofobesity.org/rates/)  Americans spend 20% more per capita than the rest of the world on healthcare, and a big part of the reason is that we are simply sicker, and almost all of that additional illness is self-induced and tied in with behavioral issues.

Type II diabetes can largely be controlled by lifestyle choices, specifically exercise and eating. Yes, I am well aware that that is not the case for 100% of people. (I also note that type I diabetes is not lifestyle-related and is a real problem. My oldest son has had type I diabetes for about 10 years. There are multiple ways to treat type II diabetes. I keep looking for anything for type I diabetes, and while a few drugs are in mid-stage trials, it has been a disheartening search.)

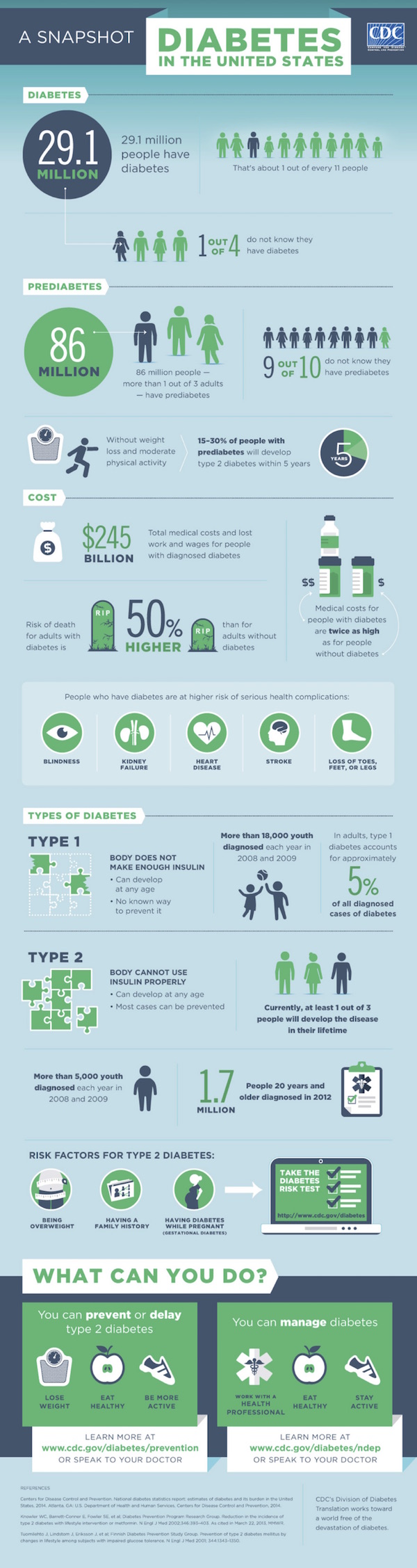

Diabetes has reached epidemic stage, not only in the US but worldwide. There are close to 30 million people in the US with type II diabetes, up from 2.2 million 40 years ago and double the number just 10 years ago. The chart below from the CDC shows that type II diabetes costs almost $250 billion a year in the US.

The Centers for Disease Control now predicts that by 2050 there will be as many as 220 million people (the high-end estimate) with type II diabetes, which would be 50% of the US population.

My friend and Mauldin Economics Transformational Technology writer Patrick Cox and I talk a great deal about the future, biotechnology, aging, and healthcare. He has just written a book called The Methuselah Effect. (He is personally dealing with a father-in-law who has late-stage Alzheimer’s.) Let me offer a few quotes from his book (for which I wrote the forward and which I highly recommend!)

The singular transformation of the 20th century was the near-doubling of life spans in the West. Longer life spans are a good thing, of course, but there is a snake in the garden.

Diseases like smallpox and tuberculosis that once were common and life-threatening nearly vanished in the 20th century West. Antibiotics turned once-fatal diseases into treatable maladies. Even the old killers, heart disease and cancer, started declining, thanks to new therapeutics. People began to live much longer lives. As a result, the incidence of Alzheimer’s increased, as did the level of horror it inflicts.

Not only does a formerly healthy individual lose memory and self when hit by AD, the lives of entire families are consumed by the slow devastation of a loved one.

Alzheimer’s patients first lose the ability to remember little things. Eventually they become delusional and forget those who love them and whom they once loved. Next, they lose motor function, moving very much like zombies, and, finally, they die, having drained the people who cared for them.

Unless your family has suffered this directly, you may not know that most AD victims reach a stage marked by hostility and anger. Nearly half of all Alzheimer’s patients assault the people around them with hitting, scratching, grappling, and biting. Sufferers of Alzheimer’s disease literally turn into the aggressive zombies of George Romero.

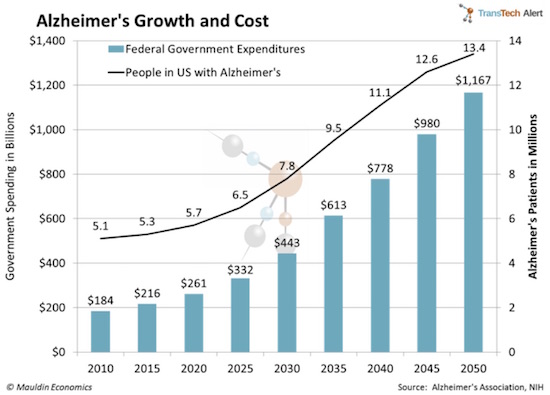

Though AD is only the sixth-leading cause of mortality, it is country’s most expensive disease, due to the many years of disabled survival it allows the patient. Despite medical progress in most other areas, Alzheimer’s and its costs continue to grow as the population ages. The zombie plague is spreading.

The numbers point to a disaster that will be the real zombie apocalypse. Western societies simply won’t be able to bear the costs of Alzheimer’s as the incidence continues to rise. Faced with impossible financial, emotional, and psychological costs, we would have to funnel so much of our resources into the care of Alzheimer’s patients that the quality of life for everyone would plummet.

Escape from the zombie apocalypse, on the other hand, is entirely simple: cure aging itself. To be more precise, the solution to Alzheimer’s is to stop accelerated aging. We need to slow the degeneration that leads to Alzheimer’s and other age-related disease.

The accelerated aging Patrick is talking about is to a significant degree caused by the lifestyle choices we make. If we can slow the process of aging (so that we live longer) and increase our health spans, those measures would go a long way toward ameliorating the looming financial catastrophe of escalating healthcare costs. And that tsunami of costs will come about whether we repeal, replace, or reform Obamacare. The issue is not simply healthcare reform – it is lifestyle reform, which is much more difficult but also more rewarding.

(At the end of the letter I will talk about some good things happening on the medical care front that give us hope.)

We all know we need to lose weight and eat better. Do that and we mitigate most other health problems. Yet we still can’t do it.

Managing the six conditions mentioned above isn’t especially hard, but it requires motivation and support. Cleveland Clinic CEO Toby Cosgrove turned his own workforce into a test case back in 2010. His key idea was to give people an incentive to avoid those six key conditions. The incentive is lower insurance rates.

Cleveland Clinic workers all see a healthcare practitioner who monitors weight, cholesterol, etc. and offers help to improve where necessary. The program, which they call Healthy Choice, isn’t mandatory but has proved very popular. That’s because the incentives are enormous. Those who meet their goals or make progress toward them can save 28% or more on their health insurance premiums.

In the process they are opting to be healthier, happier, and longer-lived.

Since the program launched in 2010, almost two-thirds of those with one or more of the six major chronic conditions managed to get them under control, and the vast majority have kept it that way. The incentive system and aggressive monitoring have succeeded in changing people’s behavior patterns. As a result, they have avoided most of the constant health insurance premium hikes seen elsewhere.

The Cleveland Clinic’s chief financial officer was initially skeptical of the program, as it cost hard dollars. He is now a believer. After the Clinic slowed the rise in its healthcare costs, actual healthcare outlays flatlined for a few years, and then last year they actually fell 2%. Very few companies in the United States with an employment population as diverse and large as the Cleveland Clinic’s can say that.

Healthy Choice has been so successful that Cleveland Clinic is helping other companies develop similar programs. One of the first was giant cement company LafargeHolcim. The company’s US unit had been told by its consultants to expect an $80 million healthcare price increase last year. But having implemented the wellness program seven years ago, the company’s actual increase came in at only $40.3 million. They literally cut almost 50% of their projected cost increase. And this is with an aging workforce population.

That’s real money saved. So we see not one but two large organizations in completely different industries both cutting their healthcare cost growth in half or more. Better yet, the employees are healthier and presumably happier, since they share in the cost savings. And similar results have been achieved by numerous other companies.

Thinking about the Cleveland Clinic’s success as I wrote about healthcare costs, I naturally wondered if a similar program would work on a national scale. If so, it would remove one of the main impediments to economic growth.

One aspect of the healthcare challenge you don’t often here about is its drag on everyone’s time. Simply finding a provider who can treat your condition and who accepts your insurance can take several phone calls. Filling a prescription can take even more calls. That’s just for yourself – the burden can multiply if you have children or elderly parents under your care.

All that time adds up across the economy. It takes us away from our work, causes us mental stress, eats up our leisure time – and often we don’t even end up feeling better. It may well explain some of the puzzling worker productivity declines in recent years. Healthcare is both a direct cost and a kind of invisible tax that sucks away time and money we could all use in much better ways.

Before we get too excited, I can think of several reasons the Clinic’s model might not work everywhere.

First, Cleveland Clinic is itself a healthcare organization. Many of its employees are trained in medical disciplines. Even those who aren’t see the healthcare process in their daily work. They’re more attuned to the importance of staying healthy, so they may respond to the incentives more readily than the average American would.

Cleveland Clinic has taken some other steps, too. They removed unhealthy options and reduced portion sizes in their cafeterias. Vending machines no longer stock sugar-laden snacks and drinks. They have on-site fitness centers, yoga classes, and other helpful activities. It all seems to be working, but not every organization is structured so conveniently. At Mauldin Economics, for instance, most of us work from our homes, and we’re spread all over the US and in several different countries. We have no way to monitor what is in everyone’s refrigerators, nor do we want to. (Although I do very actively encourage a few employees to get off their derrières and exercise and lose some weight.

I need them healthy and productive… Not to mention they are my friends, and I want them around for a long time. Thankfully, the large majority of our employees actively select to live healthy and active lifestyles.)

Another point to consider is that the Cleveland Clinic and LafargeHolcim workforces aren’t random samples of the population. By definition, these groups exclude anyone who is fully disabled, unemployed, or elderly. Those categories include some of the heaviest healthcare users.

Still, it would be fascinating to see one or more states apply something like this program to their low-income Medicaid populations. Would people stop smoking, eat healthier, exercise a little, take their meds bring to bring down their cholesterol, and work towards weight loss and other health markers if you gave them a $2,000 cash reward every year?

I suspect many would – and the rewards would be less expensive for taxpayers than treating the behavior-driven illnesses that plague our society today.

The broader finding is key: Give people financial incentives to adjust their lifestyle toward better health, and they will respond. I suspect the same will be true just about everywhere, though the specific incentives will vary. Just about the only thing economists agree on is that incentives matter. With the proper incentives people will change their lifestyle.

Making such programs work across the population will require a delicate balance of carrots and sticks. I think Cleveland Clinic was wise not to make participation mandatory for all employees. Forcing people into something like this against their will, or making it a condition of employment, is not right. But it is right to expect employees to pay more for their healthcare if they choose not to participate. At some point, when healthcare become so expensive that society simply cannot deal with the cost, I think that lifestyle choices should become a big factor in determining how much the public will pay for healthcare.

I said above that diet is a big part of the problem. You could argue that it is the problem.

We have successfully made plentiful calories available to everyone. But the kind of calories that help you stay healthy are not as easy to come by as fast food is. I don’t know how we rebuild the whole food industry to make healthy choices available to all at an affordable price. But incentives will make a difference. And the food industry will respond as more and more consumers ask for healthier choices. This is not a chicken and egg thing. We know precisely what must come first: consumers demanding healthier choices – and many evidently require incentives to do so.

But first things first. We can spend weeks picking apart these ideas and highlighting the problems with possible solutions. Far better to get started and then keep refining the programs as we learn what it takes to succeed. If next year’s price increases are anywhere near as eye-popping as media stories suggest, the new president and Congress will have plenty of incentive to try new ideas. I think we have a good model here in the Cleveland Clinic’s approach.

Dr. Mike Roizen tells me that there is bipartisan support for that approach, and even that bipartisan bills have been introduced in both houses along these lines. This is not a partisan issue; it’s just common sense. Let’s hope something can get done.

Herbert Stein famously said, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

Healthcare costs cannot keep rising on the current trajectory forever without creating a massive crisis that will force the costs to come down, either through rationing or cost controls or other draconian measures.

But there is reason to hope that the market may actually respond to some of the cost pressures prior to the ultimate crisis occurring, and at least soften the blow.

I have mentioned that there is a private company currently undertaking a phase I clinical trial of a silver bullet for cancer. We may actually have an indication of efficacy by this time next year. This is a dream candidate for cancer cures, as the side effects should be minimal and the treatment would require no hospitalization or invasive procedures. A few dozen doctor’s visits, and the cancer would be dealt with.

While this treatment may be optimal, we have no real idea yet whether it will work. As Mike tells me all the time, “Orange juice works in mice.” The animal studies with this drug were extremely encouraging, but now they’re testing how it works in the real world of human beings.

Even if it doesn’t work, there are at a minimum another dozen companies that are making real progress on the cancer front, although they are mostly focused on specific cancers rather than a generic bullet. I am hopeful that by the middle half of the next decade we will see cancer deaths plummet.

We are also seeing some encouraging results from new Alzheimer’s treatments – nothing that would seriously reverse Alzheimer’s in patients that currently have it, but treatments that might slow its onset or prevent it are no longer outside the realm of possibility.

There are numerous companies working on obesity drugs, and I would expect those to come to market by the middle of the next decade as well. Controlling obesity will take us a long way toward dealing with chronic disease in general.

As an aside, as part of research on muscular dystrophy and other muscle-related afflictions, we may find a drug that will significantly reduce the loss of muscle mass and allow those of us who have a little age on us to maintain our muscle viability, with exercise, for much longer.

While I personally do not take human growth hormone (HGH) because of the unknown or negative side effects of synthetic HGH, natural growth hormone is being used in literally hundreds of thousands of animals and causing significant growth and health improvements with evidently minimal side effects. It will not be long before that same process is available to humans. I won’t offer to be first in line to test it, but I will closely monitor results and get in the line if HGH shows the same order of effects that it has in animals. And Patrick is talking to groups working on a growth-hormone-releasing hormone that is even more amazing.

Ditto for treatment of cirrhosis of the liver. (There are phase II trials underway now.)

Here again, personal dietary choices – and especially control of alcohol consumption – may be more significant than any drug. Prevention is the best cure.

I mentioned a few weeks ago that stem cell therapy has been used to actually regenerate severed spinal cords in quadriplegics. A treatment for macular degeneration is in sight, using stem cells. Cures of many infectious diseases are less than a decade away.

There are anti-aging drugs in the works at VERY serious institutes. Pat writes about these things all the time. I get to tag along to some of his meetings, and one of the things I am fascinated by are the significant advances being made in biotechnologies across the spectrum through the use of ever more powerful computers and advances in artificial intelligence that allow for dramatic genetic modeling.

I know I am a techno-optimist, and past performance certainly does not predict future good results, but I think we are in a world where we’re about to see amazing transformations in the way we go about delivering healthcare.

And there are even significant innovations coming in terms of healthcare costs and benefits. Many hospitals and health groups are experimenting with ways to bring costs down and improve the quality of service. There is a hospital in the Cayman Islands, run by an Indian doctor, that performs heart surgery at less than 20% of the cost of the same surgery in the US, with significantly better outcomes and far fewer side effects and hospital infections. This is essentially technology that the doctor perfected in India in the course of performing and supervising 25,000 heart surgeries. Specialization can produce breakthroughs and major benefits, and those benefits are going to become noticed and imitated.

So even as the current trajectory of healthcare should make us very worried, we should all be hoping that politicians do not do anything stupid to break the innovation cycle.

And if our lawmakers were really concerned, they would replace the FDA with a drug regulatory authority designed for the 21st century and not mired in the 1960s. There are drugs and health procedures stuck in the phenomenally expensive and deeply bureaucratic process of the FDA, which is holding back a phenomenal tide of savings and health improvement.

Given a choice of replacing the Federal Reserve, balancing the national budget, or replacing the FDA with an updated system, I would not hesitate to choose FDA reform. We can actually get the biggest bang for our buck, not only in terms of dollars but in terms of health spans, by going that route. Yet you hear very few politicians talking about fixing the FDA.

And on that hopeful but cautionary note, I will close for this week.

I am speaking for my friends at the Commerce Street Bank at their annual Investment Conference on Thursday, October 27, at the George W. Bush Library here in Dallas. I am going to have to make trips to Washington DC and New York sometime in November or December, and I have a quick turnaround day in Chicago coming up this week. Also, I need to get to the Tampa Bay/Sarasota West Coast of Florida for a few meetings, some with Pat Cox and scientists looking at the latest research on a new antiaging drug. These are all relatively quick trips, so I don’t really have a heavy travel schedule for the last 10 weeks of the year. But January and February are already filling up, so my travel schedule promises to get much more typical next year. In the meantime I am really pressing on a lot of writing and other projects that have to get done soon.

This was a fun week. I got to spend some time with old friend Chris Wood of CLSA, talking about what is happening in Asia and how it affects the world. Then later that morning I was on a panel with Steve Moore and Mark Skousen (who now runs Freedom Fest) talking about how the presidential election will affect markets and the country. I got to spend some time with my old friend Steve Forbes and Art Laffer, too.

I know I mentioned Patrick Cox’s book a couple times in the letter, but let me call it to your attention again. You can buy it for like 12 bucks at this link: The Methuselah Effect. Patrick really is a special person – one of the few true polymaths I have met in my life. He is uniquely talented, and I am honored and grateful that he works with Mauldin Economics. He writes a free weekly letter on technology and transformation that you really should subscribe to and read. It will help you keep up with what is going on in our fast-moving world. You can get it right here.

And with that recommendation I think it is time to hit the send button. You have a great week. Mine will be busy, with some interesting opportunities for fun. I am meeting with Chloe Stern, who is now an editor but will soon be running the operations for Geopolitical Futures, which is the publishing arm of my friend and partner George Friedman. Not only do we share a mutual interest in geopolitics, we are also both science fiction aficionados.

I am sure my reading list will be a little longer after our lunch.

Your cautiously optimistic about the future analyst,

John Mauldin |

Home

»

Economics

»

Health Care

»

ObamaCare

»

U.S. Economic And Political

» HOW TO REBUILD HEALTHCARE RIGHT / JOHN MAULDIN´S WEEKLY NEWSLETTER

jueves, 27 de octubre de 2016

Suscribirse a:

Enviar comentarios (Atom)

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario