Islam in the West

The 30m Muslims living in Europe and America are gradually becoming integrated

Muslims have had a significant presence in the West for three generations, says Nicolas Pelham. Though both sides remain wary, they are getting closer

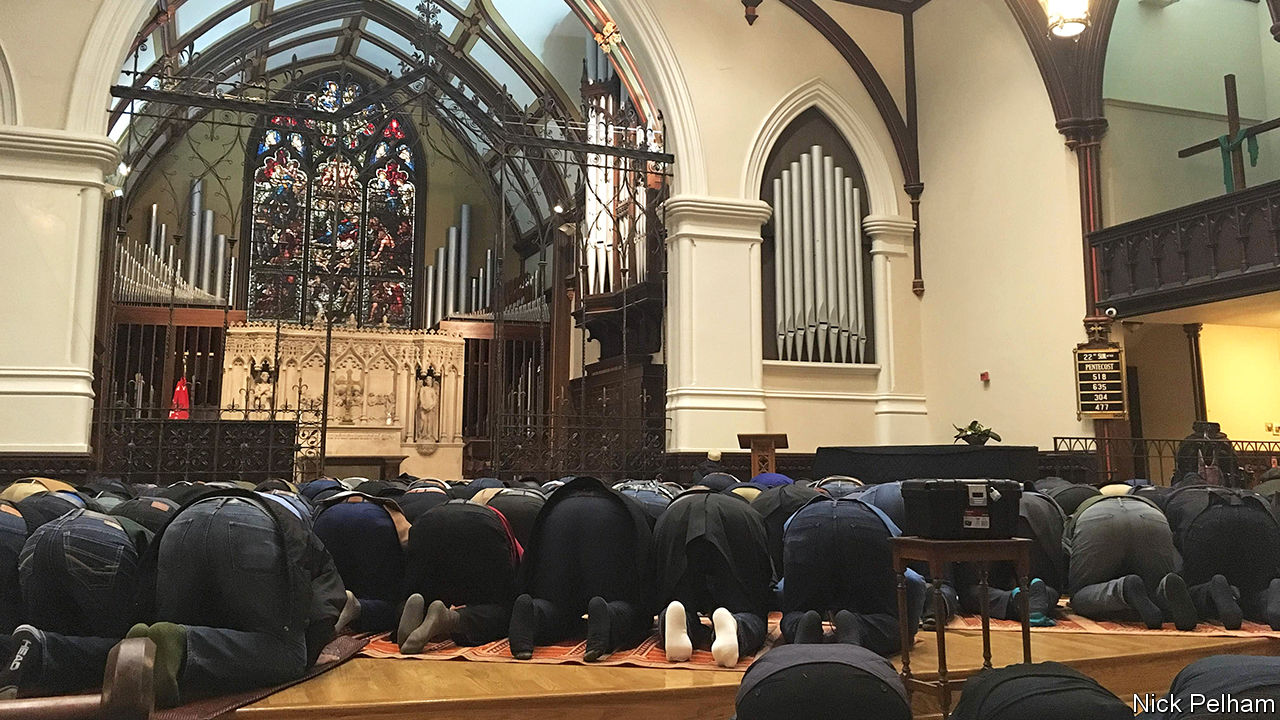

EVERY FRIDAY lunchtime, Washington’s Church of the Epiphany near the White House turns into a mosque. Hundreds of Muslims prostrate themselves in the direction of Mecca on carpets spread on the ground (pictured). The congregation includes Homeland Security and FBI agents, State Department bureaucrats and a posse of lawyers from the Department of Justice. The imam is a Treasury official. His sermons steer clear of politics.

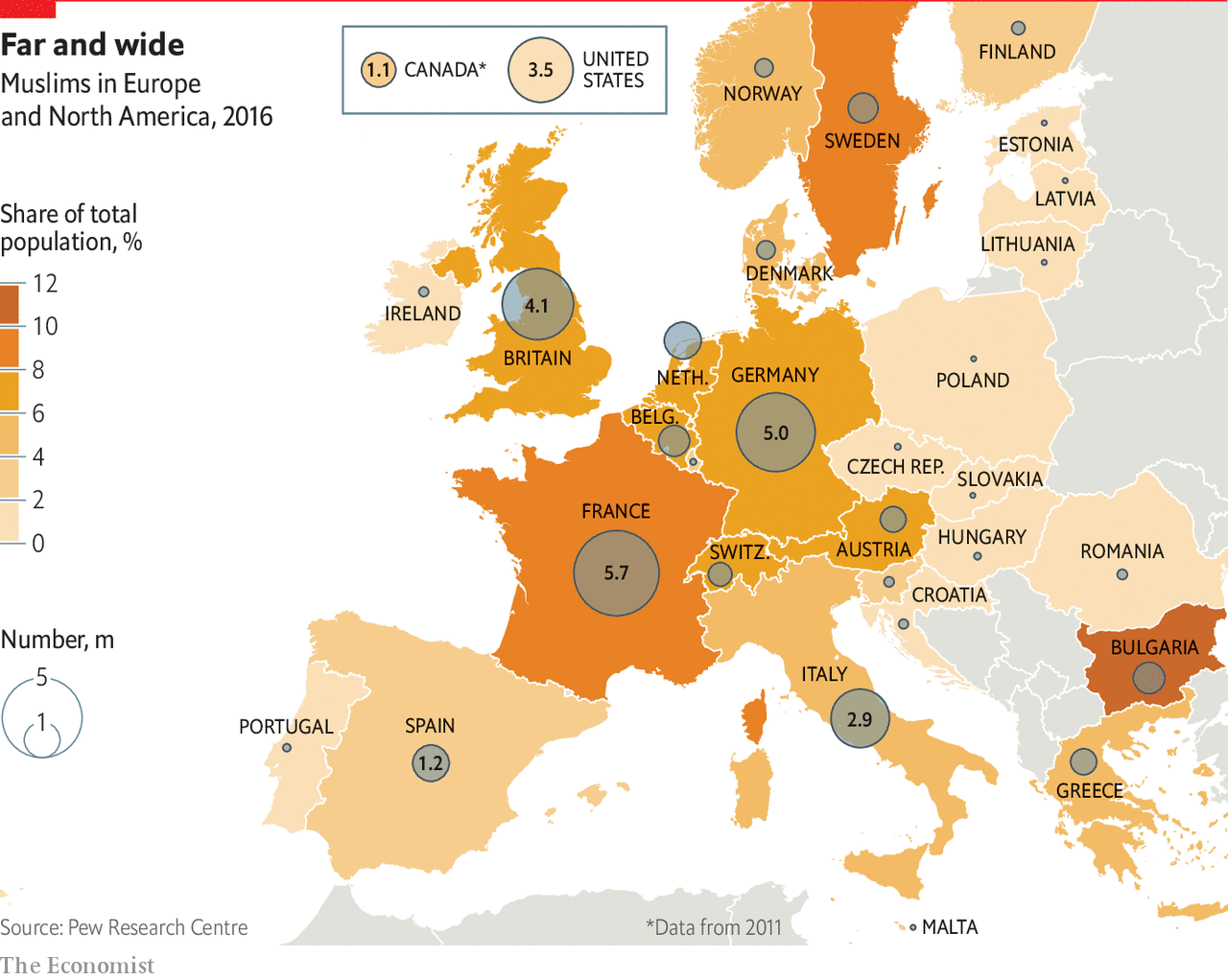

America’s Muslims have come a long way since some of their ancestors arrived as slaves from West Africa in the 16th century. From the late 19th century to the 1920s a wave of well-off Arabs came to study and stayed on, entering the ranks of America’s middle class. In a nation of immigrants, Muslims found it easier to fit in than in Europe with its more settled population. Except in a few cities such as Dearborn, Michigan, Muslims in America are thinly spread, totalling about 3.5m, or 1.1% of the population.

Europe’s relationship with Islam has been longer, deeper and more conflicted. The religion had previously entered Europe in the eighth century in Spain under a caliphate and again in the early 14th century in south-eastern Europe under the Ottomans. Both times it came in by the sword and was driven out more than half a millennium later. In the 20th century the Muslims in Europe were different from America’s, too. Millions remained after the Ottoman armies were defeated, and new ones were brought in as soldiers and workers. European powers drafted some 3.5m Muslims from their colonies to fight two world wars. Most went home afterwards, but more arrived to repair the war damage.

In the two decades after 1945 western European governments recruited hundreds of thousands of migrant labourers from far-flung places. Britain brought in Pakistanis from the Kashmiri mountains and the highlands of Bangladesh’s Sylhet; France turned to its north African territories; and Germany imported workers from Turkey’s Anatolian hills. They were expected to leave when their work was done, but instead fetched their families. Germany took its time to grant them and their German-born children citizenship. More recently an outpouring of asylum-seekers from the Muslim world’s many conflicts has changed the demography. Between 2014 and 2016 alone about 1m migrants arrived in Europe, most of them Arab. Germany took in half of them.

They asked for workers, and people came

Leaving out Russia and Turkey, Europe is now home to about 26m Muslims, who account for about 5% of its population and are typically much younger than the locals. In many European cities Muhammad (in its various spellings) has become the most popular name for a child.

Precise numbers are hard to pin down. Besides, Muslims are not a homogeneous group; they differ by religious practice, culture and ethnicity. Their experience also varies from country to country. British law protects diversity in religion and practice, whereas in France the display of religious symbols, including the veil, is banned in most public institutions, including schools. Yet French Muslims tend to be less religious than British ones, and non-Muslims in France are happier to have Muslims as neighbours and more likely to marry one.

In some ways the 20th-century wave of Muslim arrivals in the West has done remarkably well. Many of them went from the mostly illiterate edges of the Islamic world to industrial cities. They often came from large families. Their children have gone a long way to closing the gaps in education, salary and lifestyles with their adopted countries.

Muslims are also becoming increasingly prominent in Western politics. In November’s midterm elections, Americans voted two Muslim women, Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar, into Congress for the first time. London, Europe’s largest city, has a Muslim mayor, Sadiq Khan. The continent’s largest port, Rotterdam, has a Moroccan-born one, Ahmed Aboutaleb. And Muslims play a large part in Western entertainment, sports and fashion.

But the past two decades have been marred by violence and fear, too. Since 2000 more than 3,670 people have been killed in jihadist attacks in the West, 2,996 of them in America on September 11th 2001 alone. Over the same period 119 people died in anti-Muslim assaults. Jihadists make up a minuscule fringe of Muslims in the West, but those terrorist attacks turned Islam into a looming threat in many Western minds. Far-right parties fed on, and fanned, such fears. Even short of violence, the relationship between Muslims and their Western host countries was often wary or worse.

America’s Muslims until fairly recently considered themselves a cut above Europe’s. They were more middle-class, more integrated and enjoyed a more harmonious relationship with their chosen country. But a combination of America’s involvement in the Middle East, the jihadist reaction to it and a concurrent surge of white nationalism has disturbed the harmony. In a survey in 2017, 42% of Muslim schoolchildren in America said they were bullied because of their faith. One in five Americans would deny Muslim citizens the right to vote. President Donald Trump encouraged such hostility during his election campaign, pledging a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States”. Soon after coming to office he tried to impose a visa ban on six mainly Muslim countries. And last month he stirred fears of Muslim immigration again by suggesting that prayer mats had been left at the Mexican border where he wants to build a wall.

This report will explore how Muslim identity has been moulded by external and internal pressures since the mass migration to the West began in the 1950s. It will trace the impact of the laissez-faire approach Western governments initially adopted to the incoming faith and then of increasingly interventionist policies as the Muslim population grew and the relationship became more troubled. It will explore how Muslim communities have responded to policies designed to aid assimilation or improve security.

The report will also look at the generational shifts within Muslim communities as their members have adapted to life in the West. Flexibility and pluralism helped Islam flourish as a global religion for 1,400 years, but recently in the West Muslims have had to devise a theology for living as a small minority among non-Muslims, not as rulers. This is still a work in progress. The first generation of Muslim immigrants largely accepted the West as they found it and kept a low profile, unsure how long they would be staying. They brought their rituals and traditions with them and looked to their countries of origin to cater for their spiritual needs. Imams came from Turkey, north Africa and South Asia. Some Muslim countries funded the building and running of mosques.

As ties with the West became stronger, those with the incomers’ countries of origin diminished. Religion became more important than ethnicity as a marker of identity. The second generation of Muslims in the West rejected the quiet and submissive faith of their parents and looked for preachers who spoke their language and understood their concerns, often online. They wanted a religion that empowered them. At the extreme end, a few embraced violence. Jihadists are overwhelmingly either second-generation Muslims or converts.

A third generation of Muslim millennials feels more confident both of its Western identity and its Islam. It has the tools to negotiate politics and the justice system, and to interact with the establishment. Religion is increasingly becoming a matter of individual choice. The 10,000-plus mosques in the West represent the entire spectrum of Islamic belief and practice, from the Deobandis to women-led prayer. Many have left the faith altogether.

Past and recent experience has made Muslims wary of taking their future in the West for granted. But if the mainstream prevails, they are about to embark on a new phase. Three generations after their arrival, they are fashioning a theology for highly diverse societies and secular systems of government in which Islam does not hold power. In short, they are building a Western Islam.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario