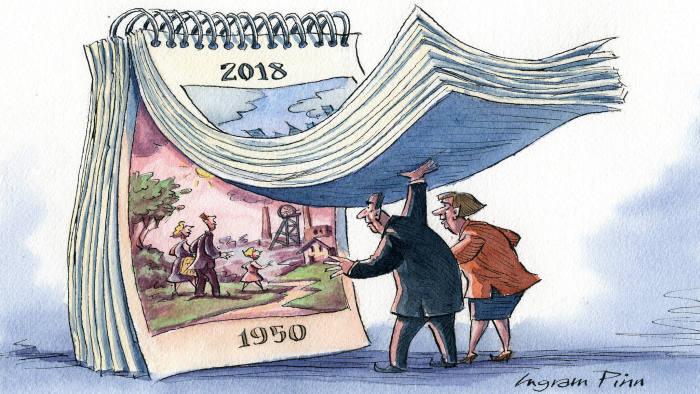

Nostalgia has stolen the future

In the US, UK and France voters seek solace in old, imagined certainties

Philip Stephens

I remember when elections were won by leaders selling visions of the future: Harold Wilson’s white heat of technology, Ronald Reagan’s morning in America or Tony Blair’s New Britain. In the new democratic disorder nostalgia has replaced optimism as a ruling emotion. Populists recognise the power of adjusted memory. America’s Donald Trump, British Brexiters, Europe’s new nationalists — they all inhabit a rose-tinted past.

Nostalgia’s force lies in a human instinct to screen out the bad while recalling the good. The tendency, I have learnt, becomes more pronounced with advancing years. Hard times become fond moments of shared endeavour and community. With the passage of years, the terrible threat of thermonuclear war can seem like the benign guardian of a stable and peaceful international system. Materially deprived we may have been, but there was something spiritually special about being spared the instant gratification of the digital age.

Baby boomers are prime offenders. My most vivid childhood memories are of a world safe for six and seven-year-olds to roam free all day, without an adult in sight, in the urban forest of London’s Richmond Park. Jam sandwiches were feasts. We managed without bottled water. I have to dig deeper into the recesses of memory to recall asking my (Irish) mother about the sign in the window of a seaside boarding house: “No Blacks, No Irish.” The reply — “Oh, pay no attention, they are silly people” — probably hid serious hurt.

The 1960s — the swinging sixties — began in Britain with a lecture about morals from a cabinet minister. Homosexuality, Lord Hailsham declared, was an “abnormality” inflicted on young boys by paedophiles. It was “contagious, incurable and self-perpetuating”. Decent sexual behaviour involved only “the complementary physical organs of male and female” — and then exclusively for the purpose of procreation.Today’s nostalgia has become an engine of nationalism. It thrives on the economic and cultural insecurities thrown up by globalisation.

Chicken Tikka Masala now counts as a favourite national dish. Yet Britain’s first curry restaurants attracted bitter local protest. They were “smelly”. How could you be sure the lamb was, well, lamb? Nostalgia draws a veil over such prejudice. Blue-collar workers, mostly male and white, were dignified by secure, well paid jobs in the coal mines, steel, or shipbuilding. Easy to forget the grisly fate of the uncles on my father’s side who died prematurely from the miners’ lung disease pneumoconiosis.

Today’s nostalgia has become an engine of nationalism. It thrives on the economic and cultural insecurities thrown up by globalisation. We look backwards for a safe identity. No one has been so adroit as Mr Trump in exploiting these emotions. When the US president promises to make America great again, he underlines the “again”. Coal miners head a hierarchy of blue collar heroes embracing metal bashers, auto workers and truck drivers. They are all white. The president’s promise is to take them back — another favourite word — to the glory days of the 1950s.

The Brexiters played similar tunes during the referendum campaign on Britain leaving the EU. Theirs was the exceptionalism of English nationalism. The arguments could have been cut and pasted from the Empire loyalists who made sure Britain was unrepresented at the EU’s founding Messina Conference. The clarion call in 2016 was as it had been in 1955 — the illusion of a resurgent “global Britain”.

In the former East Germany, the anti-migrant populists of Alternative for Germany sell a still more fanciful reimagining of the past. Ostalgie holds that the communist German Democratic Republic has been libelled. Yes, it may have been repressive, with low living standards, but it offered security, steady employment, and order. The Stasi would not have opened Germany’s borders to Muslim refugees.

Hungary’s authoritarian prime minister Viktor Orban stirs the embers of nationalism by lionising his country’s fascist wartime leader Miklos Horthy. The far-right Swedish Democrats, now promising a return to the closed, homogenous Sweden of the 1960s, have roots in that country’s Nazi movement. All the while, security is being re-described as ethnic cohesion.

Nostalgia has always had its place in politics. Respect for tradition is at the heart of Burkean conservatism. The deep irony about the now mythologised postwar decades, however, is that these were times when citizens looked unambiguously to the future. Technological advance was seen as progress, liberalism promised emancipation. The age of Sputnik, colour television and The Beatles was all about shedding the past. Its confidence flowed from the embrace of modernity. The emotions were progressive, welcoming of new technology and newcomers alike.

And now? A fascinating report by the London-based think-tank Demos observes that recent elections in France and Germany, as well as the British referendum, show the “pervasive extent” to which language that plays up the status, security and simplicity of the past has infiltrated political culture. People who have lost faith in the future are seeking solace in old, imagined, certainties.

The lesson for mainstream politicians should be evident. The nationalists will always win when the argument is framed by nostalgia. Progressive politics need a message about the future powerful enough to reclaim the voters’ collective gaze. They could make a start by explaining how to ensure our children are better off than their parents.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario