The U.S. Is Broke!

by: Shareholders Unite

- Debt scares once again resurface with US public debt at historically high levels and entitlement spending set to increase further. Some argue the US is basically broke.

- We will try to show that many of the arguments used are exaggerated and show you a country that should be much more broke, yet is thriving nevertheless.

- While not waving concerns about US public debt entirely, we think private sector debt is actually a much bigger risk, given the fact that it has caused most financial crisis.

- We will try to show that many of the arguments used are exaggerated and show you a country that should be much more broke, yet is thriving nevertheless.

- While not waving concerns about US public debt entirely, we think private sector debt is actually a much bigger risk, given the fact that it has caused most financial crisis.

SA contributor Ronald Surz wrote an alarming article on the state of the US economy, arguing that its debt levels (120% of GDP, or 390% of GDP including future Social Security and Medicare obligations) are so terrible that the US is "even more broke than we think."

The article is full of alarmist language, big scary numbers, and got a stamp of approval in the form of an editor award. But we're afraid that conclusion is simply wrong, and we will try to show you why.

Even worse…

For starters, we introduce a country with the following characteristics:

- It suffered an asset bubble crash that was three times bigger (relative to the size of its economy) than the crashes in the US in 1929 and 2008/9.

- It has the world's worst demographics.

- It has a public debt over 230% of GDP, more than twice that of the US.

If the US is broke, this country should be bankrupt already. However:

- Despite the mother of all asset bubble implosions, the economy never experienced anything remotely like an economic depression and never got anywhere close to double-digit unemployment.

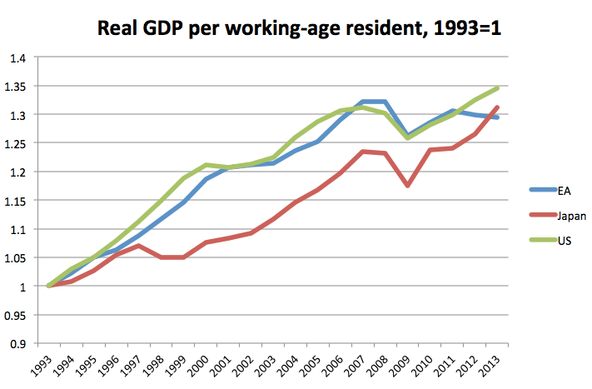

- The economy (on a GDP per person basis) has done as well as that of the US (with the benefits much more equally spread), see figure below.

- The economy has even lower employment than the US.

- Visiting the country will give everyone the impression of a rich country with little poverty or crime, first-rate infrastructure.

- The country has no inflation.

- Interest rates, despite the massive public debt, are zero.

- Its stock market has been booming.

From Devidedworld

The gap is even narrowing. If this country is broke than somebody forgot to tell it. The country we're talking about is of course Japan. It should give those who predict a terrible future for the US at least some pause for thought.

If this is what it means to live in a country that is broke, perhaps more countries will want to go broke.

Yes, we know, the BoJ, Japan's central bank is actually massively buying up Japanese debt, but despite all the predictions about this leading to massive "currency debasement", this keeps not happening.

In fact, the BoJ can't even achieve its stated target, which is a mere 2% inflation. And despite all the professed "currency debasement", the yen stubbornly functions as a safe haven investment, a place for investors to park their money when risks in the world economy increase.

Are we saying Japan shouldn't worry at all about its debt? No, we aren't. But Japan's situation is much worse compared to that of the US in all of the respects that seem to matter to the debt alarmist (much worse demographics, much higher debt, etc.) yet its economy remains rich, and the predicted crisis keeps not happening.

The fact that 'a Japan' exists should simply give the debt alarmist some pause for thought, that's all we are saying here.

Gross and net debt and assets

Surz cites a gross public debt ratio of 120% of GDP. But this figure significantly overstates the magnitude of the problem:

- Net public debt is significantly lower as there are quite a number of US Federal agencies holding a significant portion of the US outstanding debt, like the Fed for instance, or the trust funds of Medicare and Medicaid.

- As with any balance sheet, one should not only look at one side of the ledger but also at the asset side like all of the buildings, public lands, the commodity resources below the public lands (see below) etc.

On public assets, here is the IER:

The federal government owns a great deal of valuable assets both above and below ground. The above ground assets include buildings, lands, roads, railroad infrastructure, levees, dams, and hydroelectric generating facilities, to name just a few, many of which are underutilized. Below the ground, the federal government owns the rights to mineral and energy leases, from which they receive royalties, rents, and bonus payments... The federal government's total mineral estate holdings are therefore about 2.515 billion acres of lands. Thus, the federal government's mineral estate land holdings surpass the total surface land area of the nation of Canada... IER estimated the worth of the government's oil and gas technically recoverable resources to the economy to be $128 trillion, about 8 times our national debt.... IER estimated the government's coal resources in the lower 48 states to be worth $22.5 trillion for a total worth to the economy of fossil fuels on federal lands of $150.5 trillion, over 9 times our national debt.

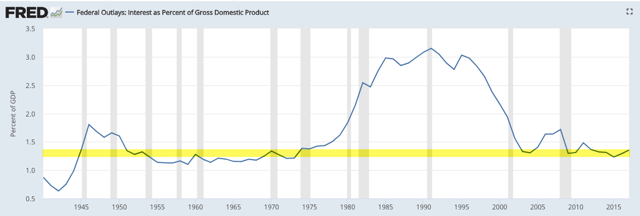

Granted, the potential income (royalties, rents, taxes, etc.) on those below the ground assets is a mere fraction of what these assets are worth, but the financing cost of the public debt is also a mere fraction of the amount of outstanding public debt (and at historically low levels, see below).

We often hear that the public debt is such a burden on future generations, but it tends to be overlooked that future generations are also inheriting the assets or stuff that was done with the money which might have improved the economy (like investments in infrastructure, education, R&D, etc.).

Future generations also inherit most of the interest rate paid on the debt (see below).

Foreign holdings and currency

The debt figures sound scary because many think of debt in similar terms as those of a household, yet this analogy is quite misleading:

- Much of the outstanding debt (58%) is simply debt to ourselves. Foreigners hold 44% of the debt, actually down from 56% in 2008.

- Unlike households, economies have more tools at their disposal to deal with the debt, like increasing taxes, growing the economy or issuing currency to liquidate the debt.

- The US debt is denominated in US dollars, the US can print these dollars at will so it can't really go bankrupt. Yes, under certain circumstances, this could accelerate inflation and/or reduce international confidence in the dollar, but these circumstances are much narrower than some would like you to believe. If you have doubts here, re-read the part about Japan above, where despite massive BoJ bond purchases, it can't even reach its 2% inflation target, and the yen is still a safe haven currency in international markets.

Take for instance growth:

If GDP growth is greater than interest costs plus new deficits, then the debt/GDP ratio will stabilize, all else being equal. Right now, the US government can borrow for 10 years at a 0.7% real interest rate; in comparison, real GDP growth was 2.8% in 1Q2018 (chart from JPM).

While the debt is large, servicing costs are actually historically low:

This also suggests that markets are not worried about the debt levels, which is at least somewhat curious because most of the debt hawks tend to be people who argue that markets are always right.

In fact, we're hard-pressed to come up with examples of a country that issued its debt in its own currency experiencing a severe funding crisis let alone bankruptcy outside of catastrophic circumstances of war or a collapse in production.

Almost all of the recent US financial crises have origins in excessive private sector debt and leverage, not public debt. We should be worrying much more about that, as it happens.

Medicare and Social Security

Another scare is the big number of future obligations of these programs, which usually run into a dozen or more trillions of dollars, a scary number indeed. But what the number relates is the present value of future obligations, simply relating these same figures as a percentage of GDP, and they will morph into a much less scarier variant.

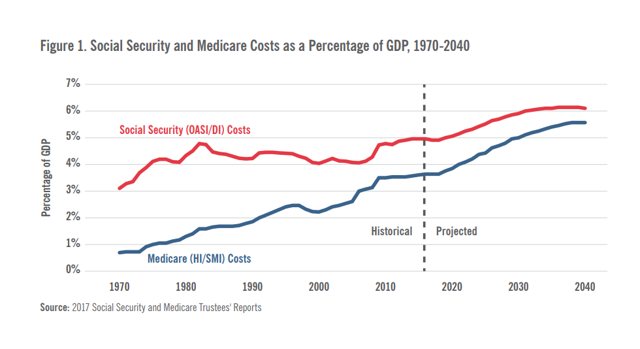

Consider the figure below:

So, over the coming 22 years, Social Security spending is going to increase by... a whopping 1% of GDP and Medicare by almost 2%. Remember, this is over a period of more than two decades. Here is Bloomberg summarizing:

Put the current intermediate estimates for both Social Security and Medicare together, and you get a funding deficit that rises from 0.1 percent of gross domestic product in 2017 to 1.7 percent in 2035 and fluctuates between 1.6 percent and 1.8 percent for the rest of the century.

If you look at the figure again, you will also notice that Social Security spending has increased from under 1% of GDP to nearly 4% of GDP since the 1970s. Yet somehow, we managed to survive that much bigger increase even if one could imagine people in the 1970s warning about an imminent crisis of terrible proportions, citing big scary numbers of trillions in future liabilities.

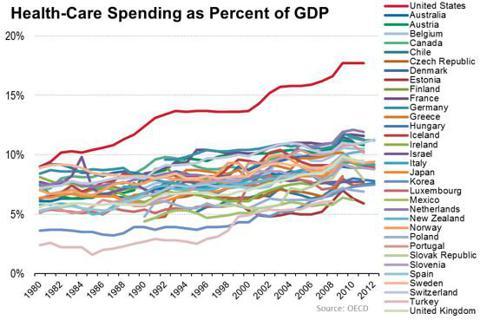

In fact, below is actually a more scary graph depicting increases in healthcare cost of OECD countries:

Source: Wall Street Journal

But we've also managed to survive this epic increase in healthcare cost. What's more, you see how much of an outlier the US is in terms of healthcare spending. It spends nearly twice as much as basically every other rich country (and that without insuring everybody and not seldom producing worse health outcomes).

Not only did the US survive that, it also indicates that if the US should reform its healthcare system and build something like other rich countries have, it could save trillions of dollars in future liabilities (not to mention achieve universal coverage, something which all other rich countries, and a good many poorer ones have).

Given the percentages involved, this could make up for the whole projected increase of Social Security and Medicare increase and then some. Gone the scary crisis.

Citing these big trillion dollar numbers in future Social Security and Medicare liabilities turns out to be simply a prop, done by people who want to scare the electorate into making cuts now as opposed to.... having to make cuts in the future (or simply raise taxes a couple of points over a period of two decades).

When these are related to GDP, the problem becomes much more manageable. For instance, the US just passed a tax cut which is projected to worsen public finances by roughly $1.9T over a 10-year period, according to CBO.

We're not the only ones who noticed. Here is the above cited Bloomberg article again:

Following Treasury's example, I estimate that the tax bill passed in December will cut revenue by an average of 1.1 percent of GDP over the coming four years (between 0.8 percent and 0.9 percent if you factor in the growth effects projected by the Joint Committee on Taxation). That's less than the 1.7 percent of GDP that Social Security and Medicare are projected to add to the deficit in a couple of decades, but (1) it's not of a different order of magnitude and (2) it's happening now rather than two decades in the future.

So, a good deal of the projected shortfall of Social Security and Medicare over the same period could have been covered without the tax cuts.

Yet curiously, when faced with those numbers, the advocates usually argue that we have to... cut spending on Social Security and Medicare. That's fine, as long as it is made clear that this is a political choice (both the tax cuts and the proposed spending cuts on Social Security and Medicare).

Then, there are the scary warnings about having to dip into the trust funds of Social Security and Medicare, here is Ronald Surz:

We are spending down the corpus, and will have spent all of the Social Security Trust by 2034, while Medicare monies will only last until 2026. This might sound like we have time, but we don't, especially since nothing is being done to head off these catastrophes. It's full speed ahead into the reckoning.

Not quite. Both these trust funds and Social Security and Medicare itself are funded from payroll taxes. When these exceeded spending on Social Security and Medicare, the excess was put in the trust funds (which bought US Treasuries) and the interest income of these helped funding the entitlements.

This is no longer the case, and we're slowly liquidating the trust funds. That sounds scary (and it is often suggested as some disaster when they run out), and it is.

But it not nearly as scary as some suggest as even if these trust funds run out completely (which will happen at the projected dates cited by Surz), we still have payroll taxes financing most (three quarters) of these entitlements.

So, we do need to raise taxes or cut entitlements or a combination of both, but even if entitlements aren't cut, the tax increases no economic disaster, given the low level of US taxes in the first place.

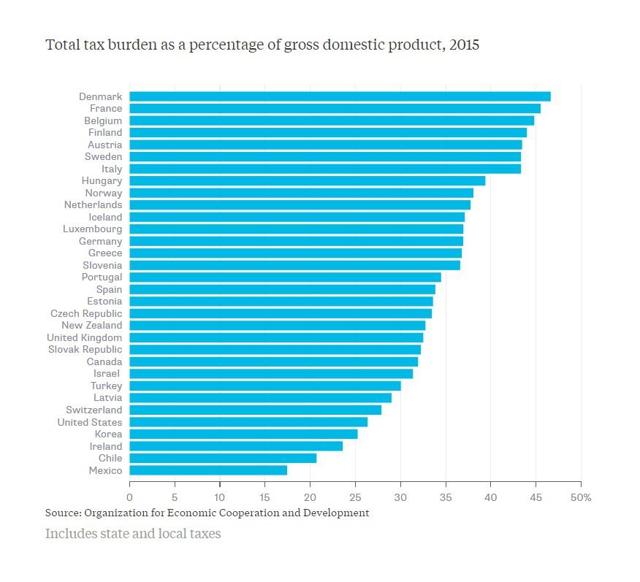

Indeed, the US tax burden is lower compared to almost all other rich countries (and lower still after the recent tax cuts, not included in the figure):

In fact, Federal tax receipts (payroll taxes are Federal taxes) are much lower still and haven't trended upwards unlike other rich countries, from the Bloomberg article:

Yet federal revenue, which has averaged 17.3 percent of GDP since 1950 and also happens to have been 17.3 percent of GDP in fiscal 2017, is projected by the White House Office of Management and Budget to decline to an average of 16.5 percent of GDP over the next four years, and given the many loopholes and outright mistakes people have been finding in the hastily written tax legislation, I wouldn't be shocked if it went lower than that.

Yet, many of the countries with a much higher tax burden, like Denmark, The Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, Austria, and Luxembourg are doing quite well economically. The US is hardly bankrupt. It still has many choices to avoid escalating public debt.

History

Apart from the Japan example, one might also appreciate what happened with all the previous worries about public debt, which is done in this instructive article from Naked Capitalism.

Larger public sector

We think the panic about US public finances has much to do with an aversion against government.

We have no problem with that, as long as people understand that this is mostly a political, not an economic argument (even if it's often cloaked as an economic one).

But as we showed, the US tax burden is low compared to most other rich countries and lower still after the recent tax cuts. Funny enough, the fiscal implications of these tax cuts were routinely waved away by the proponents, who also tend to be the ones most alarmed by the fiscal implications of the entitlement increases.

What you also should realize is that public spending tends to increase as a percentage of GDP as countries get richer, for at least three reasons:

- 'Baumol's disease' which shows that public sector productivity grows slower than the private sector, making it relatively more expensive over time (this originates from the fact that most public sector spending are services for which it's difficult or impossible to increase productivity).

- Shifting preferences; when people get richer, they tend to place more importance on a safe environment, on healthy products, on a cleaner environment, better schools for their children, better healthcare, etc. all sectors which make disproportionate claims on the public sector (through regulation, justice, law enforcement or direct government involvement).

- Economic complexity increases, which also tends to disproportionally increase claims on the public sector.

- Populations age, increasing healthcare and pension cost.

Rather than panic, we should simply accept these realities and deal with them. How, that is a political choice, but there is no overriding economic logic determining that.

Conclusion

Does the US face bankruptcy? No, not at present. While the public debt as a percentage of GDP is historically high and its future trajectory isn't looking good, there is time to act, and there is much that can be done.

Moreover, much of it is debt to ourselves, so future generations also inherit much of the interest payments on the debt, as well as the assets on the US balance sheet.

The US is an economy, not a household, and as such, it has many more ways to deal with it, like increasing growth, raising taxes (which are low compared to international standards) or issuing currency, as the debt is denominated in US dollars.

The present value of future entitlement obligations is indeed a very large number, but the size of the US economy is also a very large number. When entitlements are expressed as spending as a percentage of GDP, we see that they rise, but only by a couple of percentage points of GDP and that over a period of decades.

The rise is serious, but not beyond the scope of the US economy to deal with. The real problem lies in the dysfunctional US healthcare system, which is almost twice as expensive compared to the average of other rich countries as a percentage of GDP. That's low hanging fruit just there.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario