How we lost America to greed and envy

The US president is hostile to the core values the country used to stand for

Martin Wolf

Who lost China? This cry went up in the US after Mao Zedong’s victory in China’s civil war in 1949. It was a strange question. When did the US own China? Strange or not, this cry helped Republicans win power in 1952. It promoted the rise of Joseph McCarthy, whose politics had similarities to those of Donald Trump — above all, in the charge that traitors infest the US government. In the senator’s case, the target was the state department; for Mr Trump, it is the FBI. The question today is: who lost America? And is it lost for good?

Nobody of course owns the US, apart from Americans. Yet, for westerners and many others, the US stood for something so attractive that it seemed to be “ours” — the guarantor not just of its own freedom and prosperity, but that of hundreds of millions of others. My father, a refugee to the UK from pre-second-world-war Austria, had no doubt. The US was the bastion of democracy. It had saved Europe from falling to Nazi or communist dictatorships. As a journalist and documentary film-maker, he knew about its mistakes. But the US was not just any great power. It embodied the causes of democracy, freedom and the rule of law. This made him fiercely pro-American. I inherited this attitude.

In the postwar world, US policy had four attractive features: it had appealing core values; it was loyal to allies who shared those values; it believed in open and competitive markets; and it underpinned those markets with institutionalised rules. This system was always incomplete and imperfect. But it was a highly original and attractive approach to the business of running the world. For those who believe humanity must transcend its petty differences, these principles were a start.

Yet today the US president appears hostile to core American values of democracy, freedom and the rule of law; he feels no loyalty to allies; he rejects open markets; and he despises international institutions. He believes that might makes right. The Chinese president Xi Jinping and Russian president Vladimir Putin have might. He admires them. German chancellor Angela Merkel and UK prime minister Theresa May are decent women trying to lead democracies. He abuses them.

So why is Mr Trump in power? The answer lies with a political failure that the US might be unable to overcome. Mr Trump’s accession to power is partly an accident, but not only an accident.

The rise of China and the unanticipated impact of globalisation have profoundly affected the US view of itself and its global role. An anxiety that spreads from left to right has replaced the hubristic euphoria of the post-cold-war “unipolar moment”. The US no longer sees itself as so dominant and the world as so friendly. Mr Trump may be an outspoken protectionist. But Hillary Clinton was no defender of liberal trade. Mr Trump’s view that the rest of the world has taken the US for a ride is widely shared. In a country that has succumbed to protectionist ideas, it is not so surprising that the protectionist won. Again, once anxiety over China arrived, a nationalist was a natural choice.

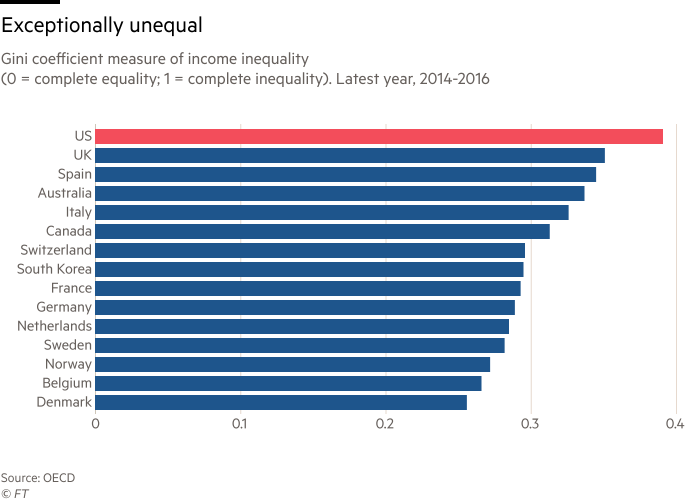

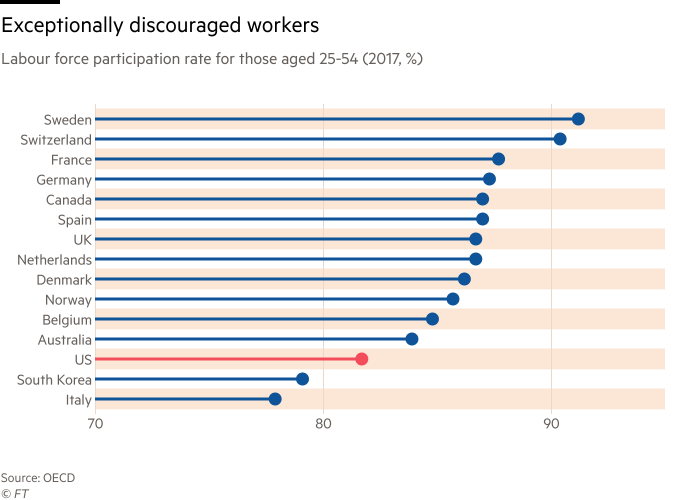

Yet something still more important is happening. The striking feature of the US economy is that, despite its unique virtues, it has recently served the majority of its people so ill. The distribution of income is exceptionally unequal. Labour force participation rates of prime-aged adults are exceptionally low. Real median household disposable incomes are the same as they were two decades ago, while mean incomes are much higher. Uniquely, mortality rates of middle-aged white (non-Hispanic) adults have risen since 2000 in the US.

Mr Trump loves to tweet his shock over every high-profile terrorist outrage in Europe. But, in 2016, there were just 5,000 murders in the EU, a rate of one per 100,000 people (including terrorist attacks). There were 17,250 murders in the US, a rate five times greater. Mr Trump might start to worry about that.

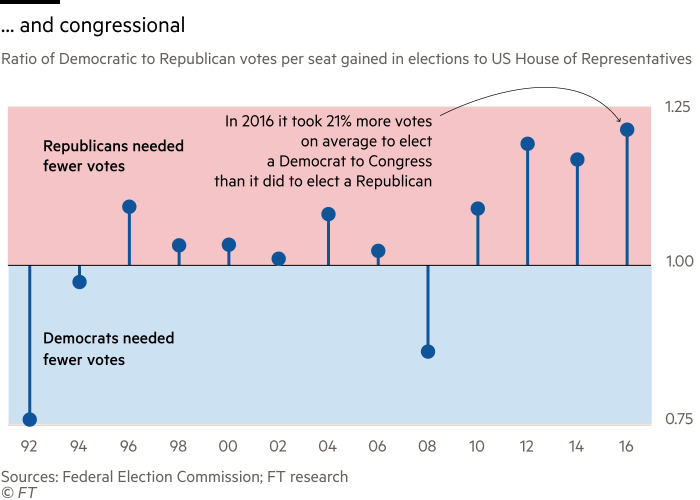

The poor state of so many Americans is in part the product of plutocratic politics: a relentless and systematic devotion to the interests of the very rich. As I have argued before, a politics of low taxes, low social spending and high inequality is sustainable in a universal suffrage democracy only with a mixture of propaganda in favour of “trickle down” economics, splitting the less well off on cultural and racial lines, ruthless gerrymandering and outright voter suppression. All this has indeed happened.

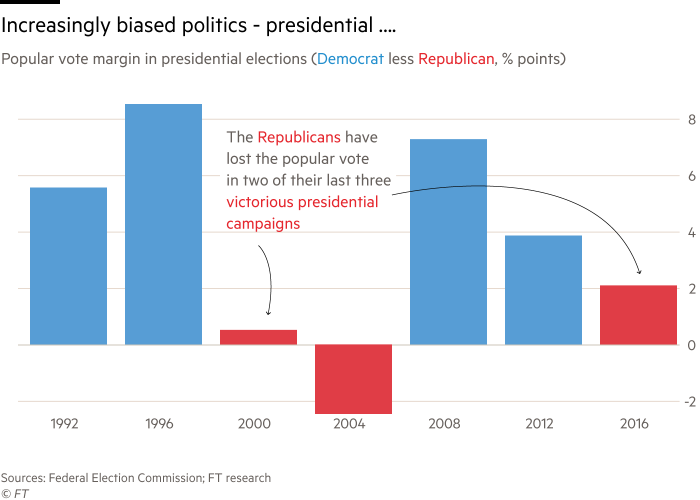

These are the politics of “pluto-populism” or of “greed and grievance”. They have been stunningly successful in making Republicans attractive to many in the white working class. The structural biases in voting are also remarkable. In the past three elections for the House of Representatives, it took 20 per cent more voters for the Democrats to win a seat than for the Republicans, on average. Republicans have also won the presidency twice in the last two decades despite losing the popular vote.

Mr Trump is the logical outcome of a politics that serves the interests of the plutocracy. He gives the rich what they desire, while offering the nationalism and protectionism wanted by the Republican base. It is a brilliant (albeit unplanned) combination, embodied in a charismatic personality that offers validation to his most passionate supporters. Will Trump’s protectionism do many in his base any good? No. But, in their eyes, he is a real leader, at last.

Who lost “our” America? The American elite, especially the Republican elite. Mr Trump is the price of tax cuts for billionaires. They sowed the wind; the world is reaping the whirlwind.

Should we expect the old America back? Not until someone finds a more politically successful way of meeting the needs and anxieties of ordinary people.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario