Public Transit Goes Off the Rails With Fewer Riders, Dwindling Cash, Rising Crime

When riders stop taking subways and buses, it’s harder to keep up service. ‘It’s becoming a vicious cycle.’

By Jimmy Vielkind

A Chicago Transit Authority train arrives at the Roosevelt train station in December. CHARLES REX ARBOGAST/ASSOCIATED PRESSSeveral of the nation’s largest urban mass-transit systems are at a crossroads, with ridership still depressed three years into the pandemic and federal aid running out.

While offices have largely reopened and travel has resumed, many commuters are only coming in a few days a week.

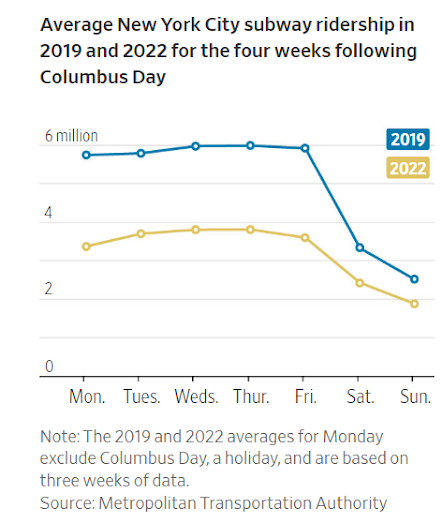

That shift has left subways, buses and commuter trains operating at well below capacity—particularly on Mondays and Fridays.

The ridership shortfall is forcing transit authorities to question their decades-old funding models for public buses, subways and trains, which are based on a combination of rider fares and public money.

On average, fares provided about a third of the operating income for transit systems nationwide in 2019, according to the Federal Transit Administration.

In major cities such as New York and San Francisco, transit authorities have been leaning on emergency funding to plug budget holes and prop up operations.

In all, Congress approved about $69 billion in three separate Covid-19 relief packages in 2020 and 2021.

Commuters board a Bay Area Rapid Transit, or BART, train in Oakland, Calif./ PHOTO: DAVID PAUL MORRIS/BLOOMBERG NEWS

Commuters board a Bay Area Rapid Transit, or BART, train in Oakland, Calif./ PHOTO: DAVID PAUL MORRIS/BLOOMBERG NEWSBut those funds are dwindling, leaving transit officials grappling with budget shortfalls and seeking new ways to fund existing service.

The ridership drop also has fueled an increase in transit crime, which in turn has pushed away more riders.

“The more you lose a ridership base, the more difficult it becomes to maintain a level of service that people are used to,” said P.S. Sriraj, director of the Urban Transportation Center at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

“It’s becoming a vicious cycle.”

In New York City, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority has disclosed plans to cut some Monday and Friday service and increase rider fares this year.

New York’s subway system has regained about two-thirds of its pre-pandemic ridership with about 91 million trips in November, according to the MTA.

But that is about 50 million fewer rides than in November 2019.

Officials worry usage has stalled out at that level.

In San Francisco, the Bay Area Rapid Transit, or BART, recorded 3.7 million trips in November—a little more than one-third of the ridership before Covid.

Systems in Chicago, Philadelphia and Boston also remain short of their pre-pandemic user numbers, deepening financial strains.

In cities such as Dallas and Cincinnati, where public-transit budgets are mostly funded through sales tax revenue and more people commute by car, user declines haven’t hit as hard.

In the U.S. overall, about 883,000 fewer people took public transit in the third quarter of 2022 compared with the same period in 2019, according to federal data gathered by the American Public Transportation Association.

The decline is particularly acute among so-called “choice riders”, people who have access to a vehicle but choose to take mass transit, Mr. Sriraj said.

This group includes office workers who tend to favor commuter rail over public buses, he added.

For New York City’s transit system—the nation’s largest by usage—changing ridership patterns are having a big impact.

Before the pandemic, subway usage peaked on weekdays, when extra trains were put in service to accommodate rush-hour crowds traveling to business districts in midtown and downtown Manhattan.

Commuters at the Times Square-42nd Street subway station on Dec. 21. New York City’s transit system is the nation’s largest by usage. / PHOTO: JEENAH MOON/BLOOMBERG NEWS

Commuters at the Times Square-42nd Street subway station on Dec. 21. New York City’s transit system is the nation’s largest by usage. / PHOTO: JEENAH MOON/BLOOMBERG NEWSRidership is now recovering faster in working-class neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx than at subway stations in those business districts.

Driving the drop in midtown and downtown users is a loss of office workers, some of whom are now going into the office three days a week, instead of five, MTA officials and analysts say.

Mark Fox, who owns Ragtrader, a bar near the Herald Square subway station in midtown, said he has noticed on Tuesdays through Thursdays that seats are full and revenue is higher.

On Mondays and Fridays, the happy-hour crowds are lighter, and Mr. Fox said he has an easier time finding a seat home on the Long Island Rail Road trains.

“I think the hybrid work model is going to be here to stay for some industries,” he said.

The MTA, which besides the subway operates buses, bridges, tunnels and commuter trains, received $15.1 billion in federal relief aid connected to the Covid-19 crisis, emergency funding that helped offset lost fares and kept normal service running.

But the authority has already used about two-thirds of the aid, including $1.9 billion in 2022. It expects to draw down the rest by 2026.

In December, officials approved a budget that includes a 5.5% increase for fares and tolls this year.

They still need to determine how the fare adjustment applies to various ticket types and hold hearings, but could increase the $2.75 base fare for the first time since 2015.

Even with the increase, the transport authority is projecting a $600 million budget shortfall this year. By 2026, the funding gap is expected to grow to $1.6 billion.

“We need to be up front with everybody about where we are in terms of having a successful funding model,” said Janno Lieber, the MTA’s chair and chief executive.

“Mass transit is like air and water for New Yorkers—we cannot live without it.”

In Boston, the region’s Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority is already having trouble keeping up with its decades-old infrastructure.

After years of deferred maintenance, the authority shut down service on the T’s orange line for 30 days this summer to catch up on repairs.

This summer, the MBTA projects it will exhaust its nearly $2 billion received in pandemic-era federal aid and plans to fill a $208 million operating shortfall with reserve funds in the coming fiscal year.

Josh Ostroff, former interim director of Transportation for Massachusetts, a passenger advocacy group, said state lawmakers need to rethink the current fare-driven revenue model.

“Public transit should not have to pay its own way,” he said.

“It is necessary to the overall economic health of the region.”

Planners for San Francisco’s Bay Area Rapid Transit say there is now stronger demand for ridership on the weekends, prompting them to add service on Saturday nights.

Subway cars at the Wellington Station train yard in Medford, Mass. / PHOTO: CHARLES KRUPA/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Subway cars at the Wellington Station train yard in Medford, Mass. / PHOTO: CHARLES KRUPA/ASSOCIATED PRESSFor BART, federal funds are expected to run out in 2025, after which it projects a budget gap of more than $200 million.

The authority plans to seek a new funding stream.

Without it, the shortfall could trigger service reductions.

One planning document shows BART would need to cut the number of train lines to three, from the current five, to break even.

Transit authorities have so far been resistant to making cuts, believing it would further depress ridership.

Officials are also concerned about delays on long-needed repairs and infrastructure improvements.

Richard Davis, a local president with the Transport Workers Union, said the MTA’s planned service cutbacks on Mondays and Fridays hurt essential workers who can’t work remotely.

“Under this plan, the people who clean those offices will get shafted,” he said.

Mr. Lieber said the service adjustments affect 0.2% of the MTA’s service and additional buses and trains will be added on weekends.

To stave off further cuts, transit authorities are seeking new revenue streams.

In New York, the MTA is preparing to charge drivers a fee to enter Manhattan south of Central Park, a system known as congestion pricing.

New York lawmakers have already approved the fee and federal officials are reviewing its impact.

New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority says it is addressing safety concerns. / PHOTO: JOHN MINCHILLO/ASSOCIATED PRESS

New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority says it is addressing safety concerns. / PHOTO: JOHN MINCHILLO/ASSOCIATED PRESSThe authority hopes to raise $1 billion a year to pay for transit improvements.

Some New York lawmakers have proposed other income generators, such as a special tax on package deliveries or drawing more revenue from sales taxes.

Lisa Daglian, executive director of the MTA’s Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee, said new state taxes on marijuana sales and casino licenses could help fund the transit authority.

“It’s not fixing a deficit,” she said.

“It’s finding a new business model.”

In the meantime, the ridership slump is creating other problems for mass-transit authorities.

In New York, more riders are skipping fares due to economic hardship and attitudes that changed during the pandemic, MTA officials say, resulting in an estimated $550 million a year in lost revenue.

In a consumer survey conducted by New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority this spring, roughly 60% of subway riders said they are riding less due to safety concerns.

Major transit crimes were up 30% last year compared with 2021, according to police.

In response to rising crime, the MTA says it has added police patrols, hired private security guards to monitor turnstiles and plans to install more cameras on subway cars.

The number of riders who said they feel safe or very safe in stations increased by 10% between November and December, according to a recent MTA survey.

Lori Romeo, a lawyer who lives in Brooklyn and works in downtown Manhattan, said she rarely goes to her office anymore and takes an express bus instead of the subway when she does.

“The homeless are sad, but the floridly psychotic and dangerous make going into Manhattan a challenging experience,” she said.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario