The politics of the yield curve

Robert Armstrong

Yesterday I wrote about how lots of smart people think that the yield curve has recently gone from being possibly too steep to definitely too flat.

To sum up:

1.- Lots of investors were confident the Federal Reserve would not tighten interest rates for a long time, and made leveraged bets on short rates staying low and long rates rising, but

2.- Inflation has stayed hot and other developed market central banks have started to tighten or started talking about tightening, so

3.- Lots of investors now think the Fed is going to tighten soon and too much, causing

4.- The short end of the curve to rise (anticipating the Fed raising rates) and the long end to fall (anticipating the Fed raising rates too much), forcing

5.- Those leveraged bets to be unwound, flattening the curve even more than it would be otherwise, a classic market overshoot.

It’s worth noting that, even ignoring the overshoot, the investors in step 3 might just be wrong.

That is, the Fed might not tighten too fast and too hard this time, whatever other central banks are doing.

I had an interesting conversation about this with Thomas Tzitzouris, who is head of fixed income at Strategas Research.

He agrees that we have over-flattened here, but he offers up a good explanation for why so many investors think the Fed will screw up — because the Fed always does:

“The Fed has made the same mistakes again and again over the last 40 years: tightening too aggressively. Even when they get behind the curve, they catch up too quickly . . .

“Since 1990 the Fed has not had reason to aggressively flatten the curve, but they have done it anyway . . . Every time we see the curve flatten, Fed staffers, board members, and chairs think they know more than all the cowboys on bond desks all over the world.”

Fed leadership always has some explanation or other for why the curve flattens ominously, other than their own ineptitude.

But, Tzitzouris says, they have always been wrong.

How do we know when the Fed has gone too far?

Any time the Treasury curve inverts.

Because there is no credit risk in Treasuries, only term premia, in theory the curve should never invert unless the short end is forced artificially high.

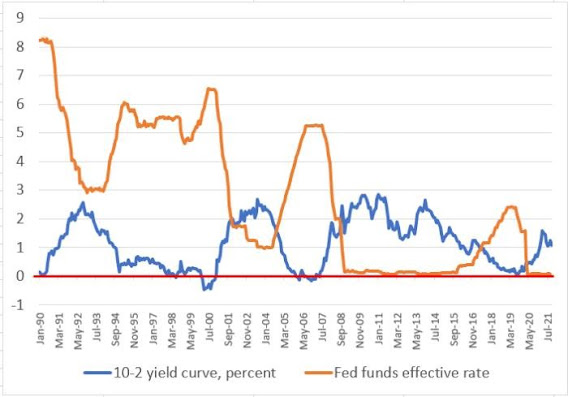

Here for context is a chart of the Fed’s policy rate and the 10-year minus 2-year yield curve spread (data from the Fed).

When the blue line falls below 0, you have an inversion:

Inversions are so bad, Tzitzouris argues, because they help Wall Street and hurt main street.

Low long rates drive the value of long-duration, high-quality assets (stocks, Treasuries, mortgage bonds, what have you) up.

Good news for financial institutions.

Meanwhile, small businesses and consumers, who borrow money at rates set on the short end, get stung.

The 2006 inversion was particularly disastrous:

“This was, in my opinion, the greatest monetary policy mistake since the Great Depression.

Simply put, this curve violated multiple rules of arbitrage, and was a warning that the Fed had tightened so egregiously, and so miscalculated the trajectory of inflation, that the curve was warning of a lost decade of near zero growth to come.

That’s more or less exactly what we got.”

If the Fed was serious about supporting main street while tightening policy, Tzitzouris says, they would do all their tightening at the long end, not just slowing bond purchases, but throwing them into reverse.

But this would get Fed chair Jay Powell fired instantly, because Wall Street would scream for his head even as the US Treasury yowled that their funding costs were out of control.

The question of Powell’s job security is of course relevant just now.

As Tzitzouris points out, Powell is an unusually dovish chair, who seems to care about what the yield curve is saying.

He might be the guy to break the over-tightening tradition.

And he could count on support form Richard Clarida, his dovish vice-chair, along with New York Fed chief John Williams.

It seems slightly odd to bet on a hawkish mistake with those three in the most important jobs at the Fed.

Furthermore, two hawkish Fed leaders, Robert Kaplan and Eric Rosengren, just lost their jobs in a trading scandal.

But the tricky thing is that President Joe Biden is about to decide if Powell will serve another term.

Any replacement is very likely to be dovish too, but how much political muscle would a new chair have to stand up to the remaining hawks, like the notorious loudmouth James Bullard, or Esther George?

Whether Powell, or whoever is next, can keep the troops in line is suddenly an important issue for investors.

Bubbles are very bad

Markets people like to make fun of GMO because the big asset manager is basically the guy who comes to the party and drones on about how unhealthy alcohol is.

Jeremy Grantham, GMO’s founder, insists we are in the biggest asset bubble since 1929 (he has said it in Unhedged, in fact).

And GMO is constantly publishing papers saying that asset valuations revert to the mean, so you should look for cheap assets and be careful with expensive ones — a strategy that has been abysmal for more than a decade.

Recently my acute colleague Jamie Powell pointed out that GMO has been forecasting negative seven-year returns for US stocks continuously since 2013. Boy oh boy has that been a bad call so far.

That said, returns at GMO’s funds have been pretty good.

Their global equity allocation fund — which should allow them to express their scepticism about the US — has returned close to 10 per cent a year over a decade, for example.

Sure, that’s way short of the S&P 500, but pretty solid for a global value fund in a decade dominated by US growth stocks.

I note all this because (to extend my metaphor) alcohol is in fact bad for you.

Owning high-valuation assets when a bubble bursts is horrible.

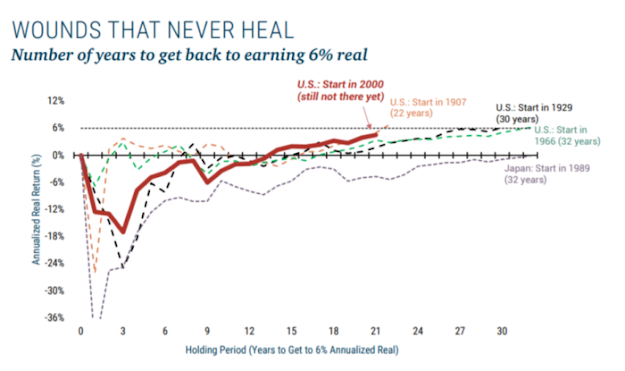

GMO has published a very nice graphic that shows just how horrible.

It tracks how long after various bubble peaks it took investors to get back to an annualised real return of 6 per cent — that is, the canonical long-term return on stocks.

“Bubbles inflict deep and cruel wounds, and it is right and prudent to avoid them, exploit them, or dance around them as best we can,” the GMO asset allocation team writes.

Now, one response to this is: well, duh. If you know you are at the peak of a bubble, and you are in a position financially and professionally to get out of the market and wait, do it.

The problem is almost everyone fails one of those two tests. Grantham may know when we are in a bubble and won’t get fired for saying so; most money managers don’t and will.

Another response is: valuations are high and we have had a great run.

Diversify away from the stuff that has done best, hold a little more cash than usual, and plan for lower returns over the next 10 years.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario