The thrust of the UK chancellor’s Budget is welcome. Yet it will not transform prospects in the near term

Martin Wolf

© James Ferguson

Rishi Sunak, the UK chancellor of the exchequer for less than a month, did exactly what he was appointed by Prime Minister Boris Johnson to do. He delivered on commitments to raise government spending, especially on investment, and “level up” the country’s more economically backward regions. He also produced a sensible response to coronavirus.

The fact that this rising Conservative star is a brilliant son of immigrants from India displays the party’s traditional embrace of fresh talent. This flexibility shows even more in the Budget’s repudiation of what the party stood for under David Cameron and George Osborne.

Gone are austerity and small government: this is now a party of high spending and big government. Its programme is “welfare nationalism”.

Rightly, the chancellor started with Covid-19. He noted the close co-ordination with the Bank of England’s welcome measures. But there are some things a government alone can do. The state is protector and insurer of last resort. A pandemic is precisely the sort of thing it exists to deal with. Mr Sunak promised the National Health Service “whatever extra resources” it needs.

Thank heavens the UK, like other civilised countries, recognises that health is a public good of the highest importance. We should never want people to refuse to go to the doctor or a hospital because of lack of money, especially during an epidemic of a highly infectious disease.

In all, Mr Sunak stated, there was £7bn to support people and businesses, £5bn to support the NHS and other public services, and an additional fiscal loosening of £18bn, to support the economy — a total of £30bn. This amounts to an overall fiscal loosening of about 1.5 per cent of gross domestic product. Nobody knows whether this amount will be enough.

Nobody knows what course the disease will take.

Nobody knows how badly it will damage the economy.

Mr Sunak is right that the shock should be “temporary”. But a temporary shock can have permanently damaging effects if the response is not strong and persistent enough.

The coalition government of 2010-15 was not, alas, the only one to have failed to understand that after the 2008 global financial crisis. One hopes that this government does understand it and will take the health and economic actions needed to get the country through this shock as well as is possible.

While the coronavirus outbreak is the immediate concern, the striking feature of the government’s new approach is described by the Office for Budget Responsibility quite directly:

“The Government has proposed the largest sustained fiscal loosening since the pre-election Budget of March 1992 . . . Relative to our pre-measures baseline forecast, the Government’s policy decisions increase the budget deficit by 0.9 per cent of GDP on average over the next five years and add £125bn (4.6 per cent of GDP) to public sector net debt by 2024-25.”

Gone is the idea of trying to shrink government: according to the OBR, total managed expenditure will rise from 39.3 per cent of GDP in 2018-19 to 40.7 per cent in 2024-25.

Gone is the notion of low taxes: public sector current receipts will rise from 37.5 per cent of GDP to 38.5 per cent over the same period.

Gone is the goal of budget balance: public sector borrowing will rise from 1.8 per cent of GDP to 2.2 per cent.

Gone, too, is the aim of declining net debt: it will fall from 80.6 per cent of GDP in 2018-19 to 75 per cent in 2021-22, but then stabilise.

This is a remarkable turnround.

The government will probably meet its manifesto targets for the current budget, maximum net investment and the ratio of debt interest to revenue. But it will not meet all three of its legislated targets.

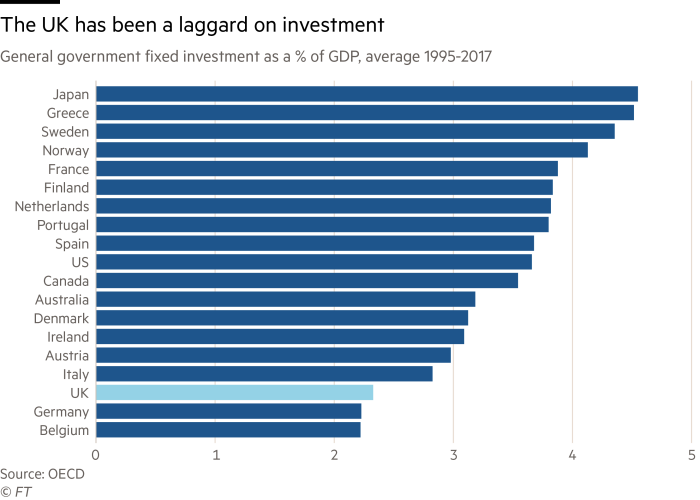

The chancellor has, rightly, announced a review of the fiscal framework. But the big judgment has been made: in an era of ultra-low real interest rates, it makes sense for the government to borrow to spend, especially on investment. I have been arguing this for a decade. The decision to cut investment right after the financial crisis was a classic bit of Treasury idiocy. Now, when the UK is close to full employment and running a large current account deficit, is no longer the ideal time to raise investment sharply. But it is still a risk worth running provided the money is well spent, which one has to doubt, given the hurry. Yes, interest rates might rise and financing might become more difficult, as the OBR notes. But these risks should be manageable.

The thrust of the additional spending — towards health, education, scientific research, innovation and infrastructure — is welcome. Yet none of this seems likely to transform economic prospects in the near term. Growth is forecast to average just 1.4 per cent a year up to 2024, about as fast as it can.

The fiscal expansion provides a largely temporary boost. On the crucial issue of Brexit, the OBR reports that this has already reduced potential GDP by about 2 per cent, relative to what it would otherwise have been.

When the UK leaves the transition at the end of this year, the costs will rise further, particularly if, as seems quite likely, no trade deal is reached with the EU. The nationalist part of the new Tory agenda still has substantial damage to inflict.

Apart from this, perhaps the striking feature of the Budget is its timidity on carbon taxation and indeed any other important aspect of fiscal reform. One must hope that Mr Sunak bends his mind to these crucial issues more boldly in his second Budget, in the autumn. The UK’s fiscal system is a mess. It needs a thorough overhaul. Mr Sunak has the brains to do the job. He should try.

So where are we now? The immediate answer is in a year of unavoidable uncertainty and worry. We also have a government that is striking out on a radical new path of welfare nationalism, partly in sensible directions, notably on public spending and investment, and partly in foolish ones, notably on Brexit.

The chancellor, as he told us many times, tried to get the job done. But there are large and worrying uncertainties, some external and some self-inflicted.

The job is not done. It never is.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario