Neither consumers nor businesses are responding as forcefully to Federal Reserve rate cuts as they used to

By Justin Lahart

The Federal Reserve, led by Chairman Jerome Powell, is expected to lower rates this week. Photo: eric baradat/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

Federal Reserve rate cuts ain’t what they used to be.

Fed officials will almost certainly lower their target range on overnight rates by a quarter point at the conclusion of their two-day meeting Wednesday, marking the third cut this year. They have framed their efforts as insurance moves, aimed at cushioning the economy against the effects of slower global growth and tariff uncertainties rather than rescuing it from recession.

The Fed’s shift from tightening in 2018 to easing in 2019 has made for easier financial conditions, with stocks at record highs and corporate bond yields and mortgage rates sharply lower. Yet it hardly seems like a fire has been lighted under the economy. Economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal estimate gross domestic product grew at a 1.6% annual rate in the third quarter after growing 2% in the second quarter and 3.1% in the first quarter.

It might be just a matter of time before the rate cuts kick in. But long-term rates, which have some of the most direct influences on household and corporate borrowing costs, started falling in anticipation of easier Fed policy nearly a year ago, leaving plenty of time for effects to filter through. The risk is that the Fed’s policy simply isn’t as potent as it once was.

Consider the housing market. Lower mortgage rates have certainly been good for it, driving a rebound in home sales. This in turn has been a plus for the overall economy, just not as much as it might have in the past.

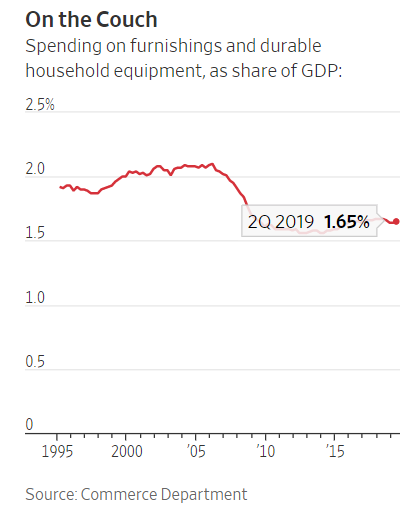

That is because housing represents a smaller share of the economy than it used to. Money spent on residential investment, which includes new-home construction, among other items, now accounts for about 3.7% of gross domestic product. In the 50 years before the last recession that figure averaged 4.9%. Similarly, money spent on furniture and appliances—items that are often bought after a home purchase—also command a smaller share of GDP than they used to.

Another way Fed rate cuts can affect consumer spending is by pushing up the value of assets such as stocks and homes. But wealth effects appear less potent than they used to be, perhaps because stock-market and housing wealth have become more concentrated in the hands of the well-to-do.

Companies also don’t appear to be responding to low rates as forcefully as might be expected. Business investment contributed far less to growth in the second and third quarters than it ought to have considering the drop in interest rates, Morgan Stanleyeconomists estimate.

One explanation is that low borrowing costs won’t induce companies to spend on new equipment if there isn’t enough final demand to put that equipment to use. So if consumer spending isn’t responding as forcefully to lower rates, neither will spending by companies. Add in concerns about global growth, trade tensions and narrowing profit margins, and it is easy to see why companies might not be in a rush to go out and spend.

New research from economists Ernest Liu,Atif MianandAmir Sufipoints to an additional factor: When rates are very low they initially lead industry leaders to invest heavily, discouraging competitors who can’t keep up. Eventually the leaders face few competitive threats and become “lazy monopolists” that don’t invest much either.

The problem is compounded by the higher borrowing costs that smaller firms tend to encounter. Small businesses polled by the National Federation of Independent Business last month said the average interest rate they paid on loans of one year or less was 6.7%, which compared with 6.9% in January. Over the same period, yields on one to three year investment-grade corporate bonds, which larger companies can issue to fund their borrowing needs, fell to 2.3% from 3.4%, according to ICE Data Services.

If the economy is less responsive to Fed rate cuts, the Fed might have to cut rates even more deeply than it used to in order to boost growth. One implication of that is that Wednesday’s expected rate cut might not be the last. Another is that whenever it faces a recession, the Fed could have even less ammunition than seems apparent.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario