The Biggest Question Facing the Federal Reserve

By Matthew C. Klein

Is the Federal Reserve right to be sanguine about inflation?

The central bank’s preferred measure of consumer prices grew just 1.6% in the 12 months ended March 31, compared with 2.0% in 2018. When asked about this at the press conference following this past Wednesday’s policy meeting, Fed Chair Jerome Powell declared there are “good reasons to think that some or all of the unexpected decrease [in inflation] may wind up being transient.” Stocks fell and real interest rates rose in response.

The immediate fear is that Powell’s interpretation of the recent data will cause monetary policy to be too tight. That could hurt stocks and other risky assets. It was only last year that excessive faith in the economy’s underlying strength led to interest rate increases that hit consumer spending, manufacturing, and housing.

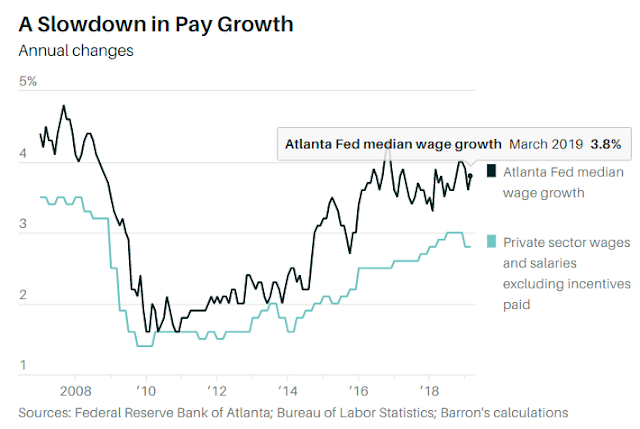

Things have improved since then, in part because the central bank reversed course after realizing it had overshot, but the unnecessary slowdown may be partly responsible for the weak inflation readings of the past few months. Both the Atlanta Fed’s estimate of median wage changes and Tuesday’s Employment Cost Index, published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, suggest that pay growth has stopped accelerating.

The deeper concern is that the Fed may be backtracking on plans to change how it treats deviations from its inflation target, which would imply systematically tighter monetary policy and slower long-term growth.

The good news is that Powell may be right about inflation, in which case those fears would be unfounded. Some indicators suggest price increases are actually accelerating.

The Fed currently aims for consumer prices to rise by 2% each year. Keeping calm in the face of one-off events is a key part of its strategy. Whether the overall price index rises faster than 2% a year, perhaps because of a spike in oil prices, or slower than 2% a year, as it did after the introduction of unlimited mobile-data plans, the central bank tries to “look through” temporary misses and focus solely on getting inflation back to 2%. The theoretical justification is that the overshoots and undershoots are supposed to cancel each other out over time.

Since the financial crisis, however, almost all the “transient” events have been in the same direction: down. The result is that the Fed’s preferred price index has grown at a yearly average rate of just 1.5% since the start of 2010.

Fed officials fear this could undermine people’s expectations of future price increases. At some point, persistent bad luck may eventually start to look like a series of deliberate choices. There is some evidence this is already happening, with the average inflation forecast collected by the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers down about half a percentage point since the end of 2015 compared with its stable 1994-2014 average. In standard theory, that should eventually lead to a new, slower trend rate of inflation.

Besides raising real interest rates today, slower inflation could make it even more difficult for the central bank to boost the economy in a downturn. (Historically, the Fed has lowered real short-term interest rates at least five percentage points to fight recessions, which means it already lacks breathing room.) The danger is that longer recessions and sluggish recoveries will reinforce this process by progressively lowering trend inflation and hobbling the Fed even further.

One possible solution is to aim for average price increases of 2% each year over time. If inflation were too low in one year, the central bank would aim for inflation faster than 2% the following year. It is unlikely any central bank possesses the level of control necessary to fine-tune price changes so precisely, however. New York Fed President John Williams’ solution is to assume that inflation will slow during recessions, as it has tended to do historically. He therefore argues that inflation should run a bit faster than 2% whenever the economy is growing.

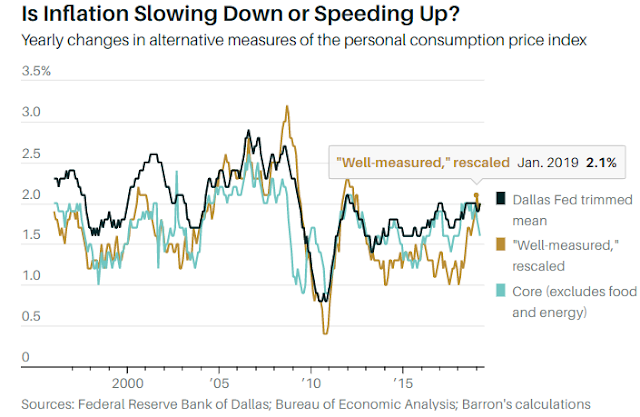

Some traders may interpret Powell’s apparent willingness to let inflation decelerate as a signal that the Fed is not moving in this direction. While that is possible, the simpler explanation is that the recent inflation data are misleading. Powell noted the Dallas Fed’s “trimmed mean” price index, which ignores price changes in the most volatile components, has been stable at 2%.

More fundamentally, the bulk of the recent slowdown can be attributed to categories in which price changes are difficult to measure. “Portfolio management and investment services” simply track the stock market, while “indirect securities commissions” are estimated rather than observed. Clothing, footwear, and jewelry are subject to the vagaries of fashion. Prescription drug prices are notoriously difficult to measure. New medicines for previously untreated ailments have no comparable prices, for example. The government claims drug prices have dropped in the past few months, but few Americans would likely agree with that assessment.

Spencer Hill, a senior economist at Goldman Sachs, recommends tracking inflation with an index based solely on goods and services with prices that are easy to measure, such as new motor vehicles, rent excluding utilities, restaurant meals, and household supplies such as soap and toilet paper. While this “well measured” price index grew just 1.3% a year between the start of 2012 and the middle of 2018, it has accelerated rapidly since then thanks to broad-based increases in the prices of appliances, furniture, household supplies, schooling, and veterinarian visits.

In the past, large moves in this price index have tended to coincide with changes in broader measures, such as the widely followed core index and the Dallas Fed’s trimmed mean. If that pattern holds, the conversation about inflation could change very quickly.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario