To revive growth, China needs to take potentially painful steps to reform its interest-rate system

By Nathaniel Taplin

The International Monetary Fund in 2017 estimated that a severe downturn could punch a hole in Chinese banks’ balance sheets equal to about 2.5% of gross domestic product. Photo: SeongJoon Cho/Bloomberg News

The cash needed to patch the holes in Chinese banks’ balance sheets probably isn’t far from the half-trillion-dollar U.S. government bank bailout after the financial crisis. But that staggering sum alone may be only the beginning of the pain.

Beijing’s half-hearted fixes since China’s deep downturn in 2015 have helped stave off an immediate financial crisis, but they severely damaged the dynamic private companies that drive growth. What’s really needed is far harder: overhauling a dysfunctional interest-rate system that breeds inefficiency.

That risks large-scale layoffs or social unrest, but failure to act could derail China’s ambitions to become a tech powerhouse and would spill over into the world economy.

International requirements for systemically important banks mean big Chinese banks still need hundreds of billions of dollars of new capital by the mid-2020s

The International Monetary Fund, in its last assessment of China’s financial system in late 2017, estimated a severe downturn could punch a hole in banks’ balance sheets equal to about 2.5% of gross domestic product, or around two trillion yuan ($300 billion). The problem would be particularly acute at smaller lenders, the IMF noted.

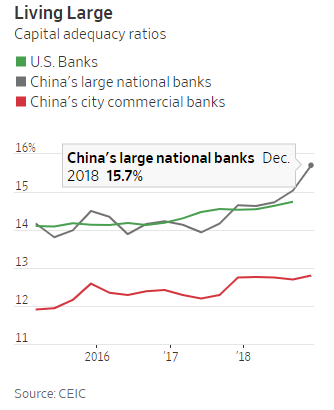

At first glance, Chinese banks now look well capitalized. Higher profits since 2016 have helped put topline capital adequacy on par with U.S. lenders.

A look under the hood is less encouraging. Most improvement has been at large banks, not the smaller lenders the IMF flagged. Overall loss provisions are equal to only 69% of problem loans, up from 2016 but down from 80% in early 2014. In the IMF’s scenario, losses at small lenders force their common equity tier 1 capital ratio—a common measure of banks’ resiliency—to just 3%. Large U.S. lenders bottomed out around 5% in 2009, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

China’s current slowdown isn’t nearly that bad. But avoiding a structural decline in future growth requires a more efficient, competitive banking system. That means letting borrowing costs rise for some lumbering state-owned companies that receive underpriced loans. And that, in turn, would almost certainly convert many such troubled loans into real defaults.

State-controlled industrial firms show only a 4% return on assets—less than average bank lending rates of 5.6%. Real interest-rate reform therefore not only requires a substantial slug of cash to bolster the banking system but also a sea change in an economic policy that has kept key state companies afloat.

Case in point: While Beijing has taken steps to shore up bank profitability by cracking down on competition from China’s notorious shadow-banking system, the main effect has been to further bolster the country’s comfortable large banks. Smaller ones that do most small enterprise lending that drives the economy have been hurt as they’ve lost a crucial source of funding and fee income.

Industrial & Commercial Bank of China ,the world’s largest bank by assets, saw first-half 2018 net interest income rise 20% according Factset. But the net interest income of small banks barely grew at all in 2017 and 2018, estimates Natixis. Small-business lending has slowed sharply.

To solve the problem, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang has told big banks to boost small-enterprise lending by 30% in 2019. This half-measure is unlikely to work without cutting off many state-owned enterprises, though, meaning more write-downs and capital destruction or tricks like shifting loans to small subsidiaries of big state-owned enterprises.

A more promising step is Beijing’s decision to permit perpetual bond issuance as a way to raise bank capital. In addition to Bank of China’s successful Jan. 22 issuance, at least four midsize lenders have announced such bonds totaling over 100 billion yuan. That is trifling, however, against the at least 1.7 trillion yuan of troubled Chinese bank loans for which no loss provisions have been made. International requirements for systemically important banks mean big Chinese banks still need hundreds of billions of dollars of new capital by the mid-2020s.

More aggressive measures are needed, like another big expansion of China’s gargantuan multi-trillion-yuan local government debt swap or a new, large-scale government-funded “bad bank.” That then needs to be followed by full liberalization of deposit rates to allow real competition for retail funds inside the banking system. This would force all banks to seek out higher-return lending opportunities.

How fast such measures materialize—and whether they even do at all—will be a key clue to China’s economic trajectory over the next several years. A timid response will mean ever-bleaker headlines about China’s slowdown.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario