Should Some Species Be Allowed to Die Out?

As the list of endangered animals worldwide grows longer, society may soon be faced with an impossible decision: which ones to take off life support.

By JENNIFER KAHN

One day last spring, Lisa Crampton stood at the base of a tall ohia tree, deep in the forested interior of Kauai. That morning, Crampton and five other field biologists had spent two hours hiking to a narrow clearing, where a hovering helicopter airdropped a large aluminum ladder. Although the distance from the clearing to the tree was comparatively short, it took the team most of the morning to maneuver the ladder across a stream, through the brush and up a steep slope. During that time, it also started to rain.

Ohia trees are tall and spindly, with a flowering red crown that spreads out in twiggy filaments. The object of the team’s efforts was a scraggly nest, about two inches wide, that was gusting around at the end of a branch four stories overhead. Peering up at it, Crampton frowned. “It’s pretty high up,” she said. “Do you think we can get the ladder close enough on this slope?”

The nest belonged to an akikiki, a small gray-and-white bird that feeds on insects, doesn’t sing much and has noticeably large feet. As head of the Kauai Forest Bird Recovery Project, Crampton is tasked with saving the akikiki, along with the rest of the island’s endangered birds. Even by conservation standards, this can be dispiriting work. Of Kauai’s eight remaining native forest birds, four are listed as endangered or threatened, including a honeycreeper so rare that researchers have managed to find just 14 of its eggs in three years, of which only four have survived.

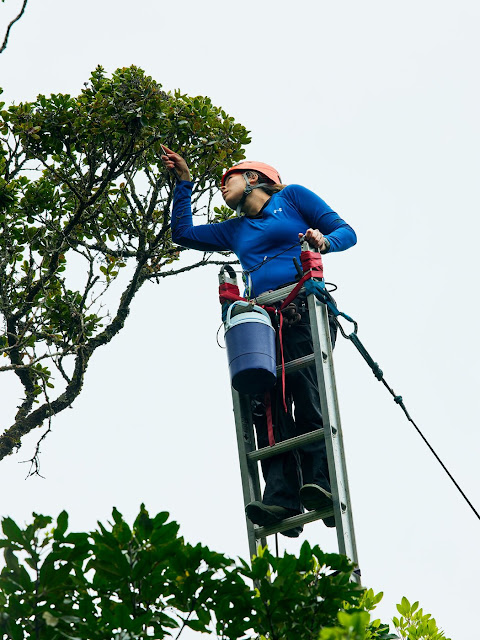

On a hike for egg collection. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

When Crampton took over the program, in 2010, it was focused on protecting a reclusive bird known as the small Kauai thrush, which had been on the verge of extinction for years. Not long after she arrived, though, the situation changed. While thrush numbers were up, thanks in part to a successful captive-breeding program, the number of akikiki had plummeted. “The surveys weren’t picking up any akikiki,” Crampton told me, “like, none.”

Because akikiki numbers dropped so rapidly — the population is estimated to have fallen by 83 percent in 10 years, thanks to a combination of avian malaria and invasive rats, leaving just 468 birds — the government approved a plan to start a captive-breeding program in 2015, using eggs harvested from nests in the wild. (When akikiki lose their eggs, they typically lay a second clutch, keeping population numbers stable.) Mandy Peterson, who has a master’s degree in ecology and is doing fieldwork with the recovery project, told me about a prop Crampton’s team often takes to island schools: a pint glass filled with 500 synthetic akikiki eggs, each the size of a small gumball. “We show them: This is what 500 birds look like. This is every bird that still exists.”

Under the rules of the Endangered Species Act, once a species is discovered to be at risk of extinction, government agencies are required by law to take steps to save it. For years, critics have challenged that mandate, arguing that it undercuts the ability to weigh a species’ value or to consider the economic impact of its preservation — for instance, the cost of prohibiting logging in a valuable tract of forest. Since Donald Trump took office, these objections have gained ground; there are currently six bills pending in Congress, all aimed at overhauling (some would say gutting) the Endangered Species Act.

For Crampton, these political developments have been alarming but also comparatively remote, at least relative to her immediate problem: getting a pair of extremely fragile eggs out of a tightly built nest at the very top of the tree canopy. This process can take up to two days, given the ruggedness of the akikiki’s habitat, a remote area known as the Alakai Swamp. That morning, after some discussion, Crampton and the team chose a spot on a 45-degree slope almost directly below the nest, and cautiously began to erect the ladder: a free-standing spire with thin, round rungs that was balanced at a precise angle and then secured with ropes lashed to the surrounding trees.

A helicopter flight to Alaka’i swamp for egg collection. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

Until recently, the Alakai held the title of the wettest place on Earth, with one to two inches of rain a day (it was eclipsed by a village in far eastern India), and the terrain is almost impossibly steep: a welter of accordion-fold ridges and deep, narrow canyons, all running with water. Because there are no trails, researchers often have to bushwhack for miles in search of nests, wading up knee-deep streams or descending knife-edge slopes spongy with deadfall and slippery with mud. In part because the terrain is so punishing, Crampton estimates that it takes roughly 130 person-hours to recover a single pair of eggs, which must then be hiked out in a heated container and flown to a special incubation facility, where the eggs will be hatched and the chicks hand-raised by specialists from the San Diego Zoo. (So far, this process has produced 39 birds, who will be bred in captivity to create a reservoir population.)

Saving a species becomes substantially harder the closer it gets to extinction, and the argument for preserving the akikiki may seem particularly tenuous. Though the akikiki perform various environmental functions, like eating insects off tree branches, they don’t appear to play a crucial role in the Alakai ecosystem. And because akikiki retreated to the highlands several decades ago and weren’t particularly noticeable in the first place, it’s hard to argue that their loss impoverishes our experience of the world. Even Crampton admitted that a majority of Hawaii residents probably haven’t noticed the bird’s disappearance, while tourists tend to assume that the island’s brightly colored tropical birds (the Mexican redheaded parrot and the Indian tricolor munia, for example) are indigenous.

One arguably legitimate criticism of the Endangered Species Act is that trying to save every creature is both unrealistic and inefficient. Because the act requires that we help all species at risk of extinction, the argument goes, agencies end up spending vital resources on less-important species, rather than concentrating on the most critical ones. Assigning value to species is a nearly impossible undertaking, because it involves a bewildering number of variables, including ecological importance, utility (coral reefs can act as breakwaters during coastal storms), the species’ place in our heritage, even its beauty or symbolism. Conservation has no formula for weighting these factors, either alone or in combination, and it’s hard to imagine one that people could agree on. How do we decide whether the wolf or the snow leopard is more valuable?

In response, some conservation groups have argued that we should put our efforts toward saving the most genetically diverse species, with the goal of increasing our long-term ecological resiliency. (In this view, saving the akikiki, which is one of 18 living species of Hawaiian honeycreeper, would be a low priority.) Others have suggested prioritizing “functional diversity”: the preservation of key species, like predators and pollinators, whose presence can radically affect an ecosystem.

All of which makes the akikiki a complicated case in point: In the face of growing political and environmental pressures, how should we decide what to save?

An incubator and other gear for the eggs. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

The conservation team looking at the nest with the eggs. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

Of the 1,280 endangered animals and plants listed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, 557 are from Hawaii, including the short-tailed albatross, the Hawaiian hoary bat and the Kauai cave wolf spider, as well as four species of turtle, six damselflies, two varieties of pond shrimp, four snails and seven kinds of yellow-faced bee. Conservationists have called the islands “the extinction capital of the world.”

This is true in part because Hawaii is a tropical paradise so fertile that seeds from a foreign plant can spread to blanket the island in the space of a few years. When the islands were new bits of volcanic rock in the middle of a vast ocean, this fertility worked in species’ favor, allowing them to diversify, Galapagos-style, into dozens of discrete niches, with few competitive pressures. In the last hundred years, though, those same factors have become a liability.

Hawaii’s tropical weather and location as a Pacific trade and tourism hub have made it a kind of petri dish for invasive species, which arrive from nearly every continent and multiply extravagantly. On the Big Island, mongoose have proliferated, devastating local bird populations; so have Puerto Rican coquí frogs, which chirp abruptly and erratically at 90 decibels, like a mobile infestation of alarm clocks. Cases of rat lungworm have risen sharply over the past five years, driven first by the arrival of the lungworm parasite, from Southeast Asia, followed by the spread of a nonnative slug that carries the disease. Kauai, meanwhile, is plagued by feral pigs, rose-ringed parakeets and a new invasive seaweed that arrived either in ballast water or in the dumped contents of aquarium tanks and that has begun to smother the island’s reef ecosystem. Since 1992, when a hurricane knocked over chicken coops, the island has also been overrun by roving bands of roosters and chickens; on my first day in Lihue, I saw dozens of them, many trailing hordes of chicks.

Faced with these cosmopolitan arrivals, island species can seem like the wildlife equivalent of a naïve Midwesterner asking a guy in Times Square to hold his wallet. Native trees and plants have often lost their defenses — the islands have stingless nettles and thornless raspberries — and in many cases grow more slowly, making them easy marks for more aggressive species like miconia, a flowering plant from Central America that grows like a weed, produces thousands of seeds and shades out everything in its vicinity. Native animals and birds don’t fare much better.

“We have a seabird, the Laysan albatross, that nests on the ground,” said Joshua Fisher, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “A rat or a cat or a mongoose can literally walk right up to it and start eating its eggs. The birds just don’t know what to do.”

And once nonnative species do begin to take over, stopping them can be a Sisyphean task. One invasive fungus that kills ohia trees can spread just from the quantity of dirt trapped in the tread of a sneaker. (To combat this, Hawaii has asked hikers to scrub their boots with alcohol or a bleach solution.) A recent study at Kahului Airport on Maui found an average of one new insect species arriving every day. In the Alakai and elsewhere, these pressures have steadily squeezed out native species, at the same time as development has left them with less land to occupy. On top of that, even when an endangered animal survives in captivity, it often can’t be reintroduced to the wild without falling victim to the same factors that drove it toward extinction in the first place.

As a result, our role as stewards of the earth is becoming more and more like that of doctors in a global intensive-care unit, trapped in a cycle of heroic, end-of-life measures. Many conservationists now operate in a state of constant maintenance: endlessly working to weed out invasive plants and predators, while trying to prop up species that have fallen into decline. At worst, an endangered animal becomes a literal ward of the state: preserved only in breeding facilities or in tiny, meticulously maintained “wild” habitats. “They’re like patients that are never going to be discharged from the hospital,” the environmental writer Emma Marris told me. “It’s a permanent situation.”

The official term for such species is “conservation-reliant.” When I spoke with Michael Scott, a wildlife biologist at the University of Idaho who helped direct the California condor research effort, he estimated that roughly 84 percent of species on the United States endangered list are currently conservation-reliant. Of those, he added, a vast majority are in Hawaii. “Hawaii is the world capital of conservation-reliant species,” Scott said.

Nicole Fernandez from the San Diego Zoo collects Akikiki eggs from a nest. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

Nicole Fernandez collecting the Akikiki eggs. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

Eggs being lowered down in the thermos with warm millet. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

It’s not surprising that, at least initially, an endangered species would survive only with outside help. Where things get more complicated is when that care becomes perpetual. Proponents of the Endangered Species Act like to point to its efficacy: of all the species listed since 1973, 99 percent are still around. The flip side, critics observe, is that only 1 percent of those species have been sufficiently rehabilitated to leave the list.

But while conservation might benefit from a nuanced discussion of how best to allocate resources around vanishing species, a far more sweeping set of proposals has recently been put forward by elected officials hoping to take advantage of the Trump administration’s willingness to weaken the environmental protections afforded by the Endangered Species Act. One bill, proposed by Pete Olson, a Republican congressman from Texas, would require a financial accounting before a species could be listed as threatened, ostensibly to prevent overspending but in practice giving local and federal governments a way to thwart new listings, especially those that might conflict with business interests like ranching, logging and development. Another, sponsored by Dan Newhouse, a Republican congressman from Washington, would change the criteria used to determine whether a species is endangered by expanding the definition of “best available” science to include studies conducted by local governments — a practice that Nora Apter at the Natural Resources Defense Council has described as “undermining the scientific listing process” by giving equal weight to potentially shoddy or biased studies.

“Behind closed doors, I think most conservationists would agree that some judicious modifications to the act could improve the situation,” Chris Costello, a resource economist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, says. But, he adds, “there’s also a real and legitimate concern that if you open the E.S.A. up to economic criteria, it will almost immediately become much weaker. Without that mandate, it’s very hard to generate the political will to save species.”

Political maneuvering around the Endangered Species Act isn’t particularly new. Since the late 1980s, critics have argued that the act limits industry and also hurts ranchers and loggers, for instance, by preventing ranchers from shooting wolves that prey on their livestock (a prohibition that has now largely been repealed). In 2008, an investigative report by The Washington Post concluded that the Bush administration managed to limit the species eligible for protection by erecting “pervasive bureaucratic obstacles” — for instance, by preventing Department of the Interior officials from using information in agency files that might support new listings.

What makes the current set of proposed bills different, Apter and others say, isn’t their content but the current political environment — a sympathetic president and a Republican-controlled House and Senate — which makes them more likely to succeed. The real purpose of the bills, opponents argue, is to create business-friendly loopholes that would drastically undermine the protections of the original law, not least because one of the biggest impacts of the act isn’t the resuscitation of an individual species but the other benefits that effort brings. According to the act, protecting a species also means preserving its habitat, a provision that inevitably helps the vast number of plants and animal that happen to occupy the same ecosystem. (A fence built to keep invasive wild pigs out of the akikiki’s breeding area, for instance, will also help protect dozens of native plants and trees, including the ohia, because it will stop the pigs from spreading invasive seeds in their feces.)

“They’re basically trying to steamroll it,” Apter told me. She said that at least one bill was also trying to make the listing requirements for endangered species more elaborate, further hobbling a process — data gathering, scientific assessment and priority and practicality evaluation — that is already backlogged. (The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service puts the number of potentially at-risk species waiting review at 550.)

When I mentioned this concern to Paul Ferraro, an economist at Johns Hopkins University, he acknowledged the danger posed to the Endangered Species Act by the current bills. But he also noted that, at a purely economic level, some trade-offs will be inevitable. “The fact is that when you spend resources on one species, you by definition are not spending them on another,” Ferraro said. “In the end, you can’t get away from putting values on species.”

An Akikiki nest. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

Before I joined Crampton and Michelle Clark, a biologist from the Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office, at the Lihue heliport for the 15-minute flight into the interior, Crampton warned me that journalists tend to underestimate the Alakai. She recalled how one photographer, who had planned to spend a full week with the team, made it just a few hundred yards before giving up; she spent the remainder of the day at the field camp. Another visitor, who regularly hiked the Sierra Nevada, was flown out after less than 24 hours. “I guess she was used to pine trees or something,” Crampton told me. “And trails.”

By the time I arrived in late May, the team had spent the past three months rotating in and out of a muddy field camp consisting of a single large tent with four cots, a Coleman stove, a laminated map and several musty plastic ration tubs. With the season winding down, the team that week consisted of just two people: Mandy Peterson and Marcus Collado, a wildlife biologist from Maine who was easygoing but prone to turning morose. Crampton called his bleaker comments “Marcus musings.”

Before coming to Kauai, Collado worked banding golden-eagle chicks, a task that required him to stand on the skid of a helicopter as it flew, then jump from the skid to the cliff-face ledge where an eagle had nested. By comparison, harvesting eggs in the Alakai qualified as a relaxing vacation, though Collado noted that “it can get a little sad” because akikiki are so scarce. “In the job interview, they warn you: ‘You may not see any birds or find any nests,’ ” Collado told me. “And I thought, Man, this could be tough.”

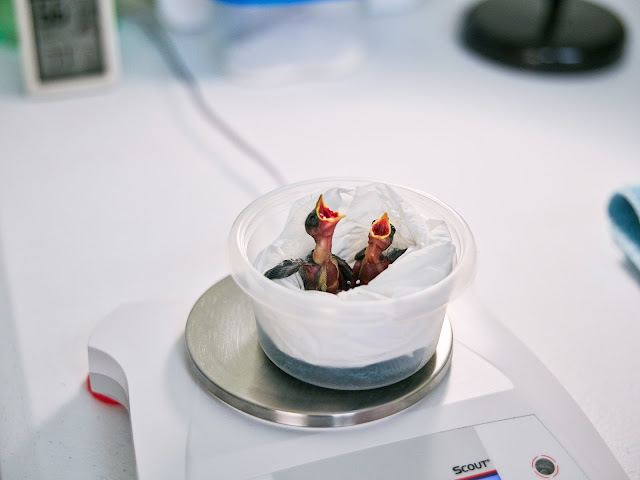

Akikiki eggs in millet in an incubator. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

When the akikiki’s steep decline was discovered in 2012, the Fish and Wildlife Service convened a panel of experts to determine what, if anything, should be done to stave off extinction. After three days of debate, the group agreed to a set of interventions, including the construction of an eight-foot-tall, five-mile-long, pig-proof fence, and the installation of what would eventually be 300 reusable rat traps, each of which to be hand-placed in key areas and stocked with bait, to keep nonnative rats from eating the birds’ eggs, their chicks and sometimes even the birds themselves, usually when a bird refused to abandon its nest.

People tend to go into conservation biology to save species, but in practice, the job can be more about killing things. The camp keeps two binders for logging information. One is devoted to akikiki sightings and nests. Another tracks rat kills and is labeled “Charlie work,” a reference to the TV show “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia,” in which a character named Charlie is regularly dispatched to kill rats. When I pointed out that the rat binder was almost four times thicker than the bird binder, Peterson shrugged. “We do a lot of rat killing. We probably kill more rats than we find birds.”

Either way, the work can be wearing. Earlier this season, the camp started keeping a dream journal, which ended up doubling as a kind of anxiety log. A few weeks back, Collado said, he had a dream in which he saw the last surviving akikiki drowning in a canal. He raced to save it but arrived too late. Not long after that, Peterson dreamed that she saw an akikiki made of Legos and knew, in that moment, that all the real akikiki had died.

I joined Collado and Clark one morning when they went to check on an akikiki nest in a valley known as Far Quarter, about two hours from camp. At a previous job on Mono Lake, the associate director of the Kauai Forest Bird Recovery Project, Justin Hite, worked with a biologist who gave colorful names to the lake’s islets — Little Norway, Little Tahiti — and in the Alakai, Hite carried on the tradition. A sharp-edged stretch became Titanic Ridge (“I’m on top of the world!”). An area that shone with a rare forest rainbow was called Unicorn Paradise. One particularly inaccessible stretch became the Chasm of Doom, but when this nickname led field teams to avoid the area, it was rechristened Kasmadu.

That day, the forest had a sleepy feel. Clark stopped to admire a tiny, lacy fern known as lady of the mountain; later, she pointed out another, larger fern covered in soft brown hairs, which were once collected to make mattresses. Surprisingly, there was almost no bird song and not even much in the way of insects, just the occasional drone of a helicopter. (Though tourist helicopters aren’t supposed to fly that low over the Alakai, Clark told me, some still do.)

By the time we got to the site, it was almost midday and hot. Because the team had already harvested eggs from this pair of birds, Collado’s task was to see whether the new clutch had hatched and, if so, to find out how many of the chicks survived. Sitting on the stream bank, Collado used athletic tape to lash a GoPro video camera to the top of a collapsible 30-foot aluminum pole. Fully extended, the pole had an alarming sway; maneuvering it close enough to see inside a nest, without hitting the nest itself, was a heart-stopping project.

Fernandez carries the eggs in the incubator to a helicopter that will take them to the egg-rearing facility. / Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

That morning, though, the main problem was getting the camera high enough; even held directly overhead, the pole was almost 10 feet too short. Peering around, Collado considered the landscape. “Justin wasn’t kidding when he said it was nearly impossible to check this nest,” he said. Spotting some scuff marks on a dead ohia tree, he began to shinny up. “I know Justin managed it somehow,” he added. “But I’ve also seen him fall a lot. He does sketchy stuff that the rest of us won’t.”

Once he managed to climb about 10 feet, Collado asked Clark to hand him the pole, which he carefully levered into the canopy, only to find that the view was blocked by leaves. For the next 20 minutes, Collado patiently worked the camera closer, while Clark watched the video feed on her phone. Finally, a blurry image of a small gray bird came into view. “There she is!” Clark said excitedly. Peering at the screen, I saw a small, disgruntled-looking bird with a slim tail and a tiny patch of white over its eye.

Over dinner the night before, Crampton described akikiki as “the little guys that at first you think are really boring, but then you spend a little time with them and discover that they have all these talents that are totally endearing. They do flips around the branches.” That morning, though, the only talent the akikiki exhibited was an unbudging perseverance.

Hoping to get a look inside the nest, Collado climbed down, assuming that the akikiki would eventually fly off to feed. It didn’t. My notes from the time say: “Been here an hour. No change. Nothing to do but sit and watch.”

The history of the planet is rife with extinctions, often sweeping ones. Roughly 250 million years ago, a cataclysmic eruption destroyed more than 95 percent of the life in the oceans and 70 percent of the animals on land, effectively erasing about 10 million years of evolution. In the past five centuries, extinctions have become less dramatic but arguably more constant: a slow drip of change as humans have spread across the globe, clearing forests, planting crops, building cities and roads.

When the Endangered Species Act was passed in 1973, it was in response to a slowly dawning awareness of how the planet was changing under human dominion. Centuries of aggressive hunting and development had shrunk the once-spectacular abundance of American wildlife to a degree that prompted widespread bipartisan alarm. The new law, which was unanimously approved by the Senate, made it a federal crime to kill an endangered animal and, more radical, established the rigorous protection measures still in place today: that once a species reaches the point of endangerment, government agencies are required to take steps to save it. At the time, this inflexibility was considered a crucial bulwark against the pressure that would be brought by politically powerful industries, like logging and drilling. “Nothing is more priceless and more worthy of preservation than the rich array of animal life with which our country has been blessed,” President Nixon said while signing the act.

Though it can be hard to imagine today, the Endangered Species Act was intended to be a starting point rather than an endgame; a last-ditch way to save species that were vanishing until more comprehensive and farsighted conservation plans could be put in place. As Chris D. Thomas, an ecologist and evolutionary biologist at the University of York, puts it, “The fact that we reach this point, with all the heroic measures, shows that we’re not great at planning ahead.”

Lisa Crampton, head of the Kauai Forest Bird Recovery Project. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

But it’s also true that extinctions just seem to get to us. We make a modest effort as a species dwindles and then, when it’s really on the ropes, we suddenly panic. “There’s just something gutting about a thing being lost to us forever,” Thomas says.

More debatable is the degree to which extinctions are genuinely catastrophic. Do these disappearances represent the loss of rare, beloved plants and birds? Or are they simply the next evolutionary step in an ever-changing, increasingly global ecosystem? When I spoke with Thomas, he supported the idea that truly invasive species — the kind that transform the landscape — may need to be contained. But it’s also true that the early isolation of the Pacific islands was itself an artifact. “If you look at it cruelly and unemotionally, Hawaii has native birds and introduced birds,” he told me. “The native birds are dying out, and the introduced birds are malaria resistant. Are the introduced birds worse? Not necessarily. You could argue that this is simply a case where island species have lost out and continental species have won.”

In this view, the loss of Hawaii’s native birds and plants and their replacement by species that are more resistant to disease and predators, is just another case of the fittest surviving. If humans have accelerated this process by planting Argentine pampas grass in their gardens or by dumping tropical aquarium fish in their local lake, it’s still just a faster, looser version of what has been happening on the planet anyway: Starbucks in Paris and McDonald’s in Soweto; Australian brown tree snakes in Guam and Asian carp in the Great Lakes.

In short, it’s fair to ask why, exactly, biodiversity matters. As Thomas says: “Even if we were to lose 10 percent of all species in the next hundred years, would biology stop? Would ecology stop? No. In fact, most people wouldn’t even be aware of the loss.” Given how radically we’ve already altered the landscape, how bad would it be if we just kept doing what we’re doing: paving the land, overfishing the oceans and letting the chips fall where they may?

Faced with this dilemma, some conservationists have tried to shift the focus to an economic argument known as “ecosystem services”: the idea that we benefit from preserving biodiversity either because it saves us money (mangroves prevent coastal erosion that we would otherwise have to handle with an expensive engineering project) or because it contains something of value to us, either now or in the future. For instance, a biodiverse planet may provide a first defense against global warming. Or it may act as a repository of potential discoveries: new materials that mimic the strength of spider silk; drones modeled after insects; an anticancer drug derived from Amazonian moss.

The ladder used to reach the eggs being flown back from the field. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

While all this may be true — mangroves do prevent coastal erosion; research into new cancer drugs derived from plants is underway — it can also sound wishful, like a hoarder arguing that his pile of junk might someday contain collectors’ items. The difference, Thomas says, is that unlike a hoarder’s pile, ecosystems perform vital planetary functions, like keeping soil fertile, preventing desertification and absorbing carbon dioxide. The reason some conservationists want to prioritize genetic or functional diversity isn’t that either of those things are inherently valuable to people, though they can be, but because they’re essential to the health and resiliency of ecosystems themselves. The true problem, then, is not whether we would notice those vanished species and ecosystems; it’s that there’s no good way to quantify the opportunity cost of our loss, which in turn can lead us to underestimate it. “The species we have now are the ancestors of all future species,” Thomas says. “And I don’t think we know enough about ecology or evolution, or how humans are going to affect the planet over the next thousand years, to bet on which animal or plant to keep.”

All of which makes it hard to know where to draw the line. We can’t put every ecosystem in the world under glass. (We can’t even manage to do that on Kauai, a 500-square-mile island in the middle of the Pacific.) Even if we could, conservation isn’t always an ethically straightforward choice; in countries like Brazil and Kenya, do we prioritize protecting wild animals and their habitats or the farmers facing hunger who hunt those animals and who log forests to plant crops?

Presumably, though, we also don’t want a planet that’s nothing but pavement, cattle farms and monoculture farmland. The biologist E.O. Wilson eloquently argued against living in a world of crows and rats, and against the loss of beautiful, fragile species like snow leopards, white rhinos and tiny mouse lemurs; even if you never see a lemur or an arctic fox in person, the world can be a richer place by having such creatures in it. Others simply see conservation as a moral duty: because we’re the ones creating these problems, isn’t it up to us to fix them?

Whether we regard conservation as an ethical or an economic issue, we’re still faced with the question of how we decide what to save. In an ideal world, Michael Scott told me, conservation science would have the resources to study this question, rather than being stuck reacting to the latest crisis. “Figuring out which species and ecosystems are the most important to protect is a complicated project,” Scott says. “At this point, just coming up with a list of qualities we want to investigate would be a good start.”

But for such an approach to take hold, the conservation movement would have to undergo a profound shift — away from triage mode and toward a more coherent and deliberate plan for global conservation. And such a shift would most likely require more resources and more political support than currently exist. The question is whether it will happen in time to shelter us from some of the more significant changes that climate change and development are likely to bring.

Nine-day-old akikiki chicks that were hatched at the egg-rearing house on Kauai. Credit Spencer Lowell for The New York Times

One overcast morning, I drove up a winding road hung with vines to the Egg House, where recovered akikiki eggs are incubated and hatched. Mapping my route that morning, I envisioned the Egg House as a sophisticated research lab, stocked with high-powered equipment in temperature-controlled hatcheries. Instead, I found myself driving past suburban cul-de-sacs, lined with tidy houses, lawns and miniature palm trees, until I reached a small bungalow overlooking a forested canyon.

To say that the Egg House was no-frills radically understates things. Aside from the room housing the chicks, which has air-conditioning, the house is humid and almost completely empty. In the living room, someone had set up a single cot, with a sleeping bag.

That summer, the hatching and raising of the akikiki chicks was overseen by Amy Klotz and Becky Geelhood, from the San Diego Zoo’s Institute of Conservation Research. Klotz, a thin woman in a turquoise Kauai Forest Bird Recovery Project shirt, described the work as exhausting. Chicks must be fed every one to two hours and are weighed every day. “I lie awake nights wondering, Why didn’t that chick gain any weight since yesterday?” Klotz told me.

In principle, captive breeding will keep a species alive while conservationists try to change the environmental factors that killed it off in the first place. But recreating the many conditions that allow a species to thrive can be staggeringly complex.

When I spoke to Bryce Masuda, a conservation-program manager who oversees the captive-breeding program for the akikiki, he said that whether species reproduce can depend on complex cues in their environment: one bird might be signaled to mate by the appearance of a particular fruit, another by the abundance of a particular flower. Though zoo personnel do their best to replicate those conditions, Masuda told me, it can be difficult to determine what the important cues are. “With the akikiki, we increase the number of insects they get in the late winter and early spring,” Masuda said, “because we’re hoping that that will be a cue for them to lay eggs. But do they also need certain plants in their enclosures? Does the amount of rain each year matter? A lot of it, we just don’t know.”

Even should the akikiki overcome these hurdles, it will most likely remain susceptible to avian malaria, which has begun spreading into the last of the island’s protected areas as the weather has grown both warmer and drier. When I asked Masuda why we should try to save the akikiki, given that it might never be able to survive in the wild, he demurred; even now, he said, the University of Hawaii was developing mosquitoes that would produce sterile offspring, significantly reducing the risk of avian malaria.

In theory, the potential for revitalization exists for most conservation-reliant species, even those, like the akikiki, currently on life support. When the California condor was on the verge of extinction — largely as a result of lead poisoning from eating animals shot by hunters but also because of their tendency to fly into power lines — David Brower, the former director of the Sierra Club, urged conservation groups to give the species “death with dignity.” (His view did not prevail, and the population is now back up to more than 440.)

The peregrine falcon was similarly conservation-reliant for years, then rebounded after Congress outlawed DDT, which had been weakening the birds’ shells; they can now be seen nesting on New York skyscrapers. “Even if a species is dependent on us now, it may not be dependent indefinitely,” Chris Thomas says. But it’s not easy to see which species will eventually win out. In the case of the akikiki, Thomas says, unless something radical is done — impairing the vectors of the disease, or making the birds resistant with gene therapy — the birds will never survive in the wild. There may be a solution around the corner, or there may not.

In the meantime, Geelhood and Klotz maintained their assiduous vigil. Because someone has to be watching over the eggs at all times — even an ordinary power outage could be lethal — the responsibility could be all-consuming. “Sometimes I won’t leave the house for days,” Klotz said. “Not even for 10 minutes to go to the store.”

This sense of urgency was coupled with an awareness of just how long the odds for an endangered species can be. “You’re basically terrified all the time,” Klotz told me. “It’s a lot on your shoulders when there are 500 birds left in the world.”

Credit Illustration by Hagar Vardimon

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario