PROGRESS ON MANY FRONTS: NEW TYPES OF THERAPY MEAN CANCER IS GOING TO BECOME EVER MORE SURVIVABLE / THE ECONOMIST

Progress on many fronts

New types of therapy mean cancer is going to become ever more survivable

Science is making cancer treatments more precise in many different ways

THERE are few whose lives have not been touched by cancer. It cuts down friends, loved ones, siblings, spouses, parents and children. And it does so more than it used to. A generation ago, one in three people in the rich world could expect one day to hear the fateful words, “I’m afraid you have cancer.” In some countries it is now approaching one in two. The longer other things do not kill you, the more of the wear and tear that leads to cancer your cells accumulate. Live long enough and it will be the reward.

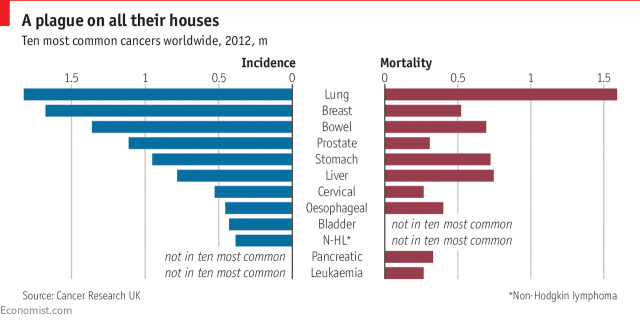

Worldwide, cancer is the second leading cause of death after heart disease; it killed 8.8m people in 2015, three-quarters of them in low- and middle-income countries. Between 2005 and 2015 the number of cases increased by 33%, mostly owing to the combined effects of ageing and population growth. New cases are expected to increase by 70% in the next 20 years.

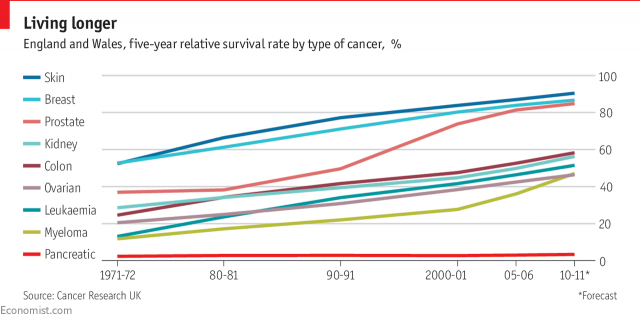

Set against this rise is the fact that, in rich countries, cancer is becoming more survivable. Today 67% of patients in America will survive for at least five years. Different cancers fare differently, as do different sorts of patients—cancer has proved more treatable in children than in adults. Some cancers, such as that of the pancreas, have seen barely any improvement. But there are general grounds for optimism.

New research tools, such as easily generated antibodies, rapid gene sequencing and ever easier genetic engineering, have revolutionised biologists’ understanding of cancer. This understanding has allowed more specific approaches to the disease to be developed, and the trend will continue. What is more, the tools of molecular biology have moved out of the lab and into the clinic. Genetic tests are used to find the precise vulnerabilities of a particular patient’s cancer. Antibodies attack the specific molecules that have gone haywire. The cells of patients with cancer are engineered to better fight the disease.

And in the current decade a whole new branch of therapy has sprung up. Unshackling the immune system’s response to cancer, once a pipe dream, has become practical medicine, with approved therapies for eight kinds of cancer. The excitement at oncology conferences is palpable.

As these advances have arrived regulators have increased the speed with which treatments for life-threatening diseases are approved. This is in some ways a mixed blessing—some expensive drugs with little if any benefit are nevertheless getting to market. But it has encouraged an unprecedented wave of investment and innovation. The pipeline of oncology drugs in clinical development has grown 45% in the past decade. There are currently about 600 drugs under development at biotech and pharma companies.

The picture is not uniformly rosy. In both treatment and prevention the poor are ill served. Basic chemotherapy and pain relief is difficult to come by in many parts of the world. The failures are not limited to poor countries. Cancers due to bad diet, obesity, alcohol abuse and smoking could all be reduced a great deal in wealthy ones. And while vaccination against human papilloma virus is routine in Rwanda, it is still limited in America—which means thousands of American women will face cervical cancers they could have avoided in years to come.

But if some low-hanging fruit still go tragically, lethally unpicked, progress is not merely possible. It is happening.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario